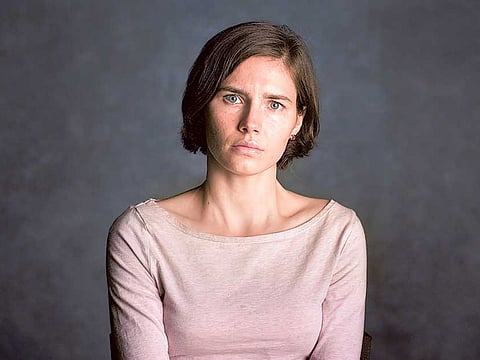

Amanda Knox: A psychopath in sheep’s clothing?

The subject of a new Netflix documentary is as divisive a figure as ever

“Either I’m a psychopath in sheep’s clothing or I am you,” declares Amanda Knox in a new feature-length documentary. Her gaze is steady, her voice doesn’t waver: in short, Knox is as cool and intriguing as she was nine years ago when her roommate’s blood-soaked body was found in Perugia. Many believed she had a hand in the murder — and many still do, despite her conviction being overturned by Italy’s Supreme Court last year.

Amanda Knox, premiered at the Toronto International Film festival and released next week on Netflix, is billed as a definitive account of the killing — thought to have been a sex game gone wrong — and its aftermath. That Netflix is trumpeting the film to launch its autumn schedule, hard on the heels of its successful drama House of Cards, is testament to the enduring fascination with Knox, 29. As filmmakers Brian McGinn and Rod Blackhurst put it, she is either a woman who’s been terribly wronged “or a devil with an angel face”.

Knox has returned to her home town of Seattle, where McGinn and Blackhurst first met her in 2014. They found a poised but wary young woman, resentful of constant scrutiny. “I get in line at the grocery store and the person behind me will say, ‘Woah, I know you!’” she told them. “I want to say, ‘Who the [expletive] are you? And you don’t know me.’”

The former linguistics student finally finished her degree last year and now works with prisoners who claim they were wrongly convicted. In August, she moved into a new home in Seattle with her boyfriend, writer Christopher Robinson, but the ordeal in Italy, where she was convicted and exonerated twice, is always there.

Even as she wrote that she was “thrilled” by her change in circumstance in a recent blog about the move, she could not help reflecting on times past. “Just as our relationship is more than the sum of Chris and Amanda, so must our home be more than the sum of our stuff. I’m reminded of how my cell in Capanne prison [in Perugia] transformed in character with the arrival or release of even just one prisoner. While none of us was allowed much in the way of material possessions, our combined emotional baggage, when bashed together without consideration, could make an already inescapable situation insufferable, even dangerous.”

This ability to analyse her experience surprised the filmmakers. “She has this incredible bird’s-eye view of the situation because she’s been thinking about it for so long and she’s trying to understand and intellectualise it,” says Blackhurst. “Time has given her perspective.”

When he and McGinn first flew to Italy in 2011, while Knox was in prison awaiting appeal, they didn’t know whether she or any of the other main players in the story would agree to talk. “We were just interested in getting a sense of why this story that happened four years prior was still headline news all over the world, and how something that was such a tragic event could be turned into this nail-biting, gripping entertainment,” he says. “A lot of people were turning stories around fast to keep their audiences on the hook. We wanted to set our pace so we could do something that had some larger truth about why these things happened, instead of a whodunit.”

The result is a detailed, compelling film that scrupulously avoids assigning innocence or guilt but examines the evidence through film made at the time, intercut with long interviews with Knox, her then boyfriend Raffaele Sollecito and Guiliano Mignini, the lead detective on the case. Some think the filmmakers have been too sympathetic to Knox, allowing her once again to portray herself as the “victim”, but they insist she laid down no conditions for taking part.

Kercher’s family declined to participate. Mignini sadly recollects meeting her mother at the mortuary, where she asked if she could kiss Meredith one last time.

The story that became global news began when Kercher, who was from Croydon, south London, arrived in the hilltop town of Perugia in autumn 2007 to spend a year studying in Italy and ended up sharing an apartment with Knox. Kercher, 21, daughter of a British father and Indian mother, was reserved and demure.

Knox — or “Foxy Knoxy”, as she styled herself on her MySpace page (friends said because of her speed and ability on the football pitch) — was a party girl. Knox, then 20, had gone to Italy to become independent, she told the filmmakers: “Before Italy I was quirky and ridiculous I thought it was important to get out of my comfort zone and see if I turned into an adult.”

Later, having spent the previous five nights with her new boyfriend, Sollecito, Knox got to her apartment and found the door open. It struck her as odd, but not sinister. She had a shower and only then noticed smears of blood on the floor. Kercher’s room was locked. When the police arrived, they found the British student, her throat cut and bloody fingermarks on the wall.

As police and forensics experts sifted through this scene of horror Knox, looking sad but composed, stood outside kissing Sollecito. Later, in the long waits between police interviews, she was seen turning cartwheels and doing stretching exercises. “Amanda says people respond to tragic events in different ways,” says Blackhurst. “She was very young, but her behaviour was odd and that was definitely a big part of the case. The other thing people keyed into was sex. That fuelled the fascination with her.”

Though Knox has always denied being at the house the night Kercher died, the theory police eventually put forward was that an unwilling Kercher had been forced to take part in a sex game by Knox, Sollecito and Patrick Lumumba, the owner of a local bar where Knox worked — she implicated him when she was questioned by police. Lumumba later said that Knox’s acquittal was a triumph for being “American and rich” rather than for justice, though the Supreme Court ruled that there had been “stunning flaws” in the case against her and DNA evidence that had seemed damning unravelled on re-examination. Rudy Guede, a local drifter, was eventually convicted of the murder and is still serving a 16-year-sentence.

The combustible mix of beautiful young women, sex games and betrayal set the internet alight and the controversy still rages.

The killing has become iconic because it happened at a particular moment in history, says McGinn. “Facebook and social media were starting to become huge and the line was starting to blur between hard and soft news.” Facebook yielded damning pictures that made new headlines every day: Knox messing around with a hunting rifle and Sollecito at a fancy dress party, carrying knives.

“She is a kind of cipher or enigma. Judgments are made on her actions, whether she blinks at the right time or smiles at the wrong time,” says Blackhurst. “She knows this case might define her forever and that’s terrifying.

“Maybe she’s the person you would least suspect, or she’s the innocent caught up in a nightmare.”