Empowering the less-abled with cane

Rise Legs, Arun Cherian’s Bengaluru-based startup venture, offers cost-effective mobility aids for physically-challenged individuals

It must have been around four in the evening when Prajwal regained consciousness. Looking around, he noticed his uncle lying on the ground and his motorbike fallen on its side and glass scattered on the ground. Then he remembered riding pillion on the bike. They were returning to Bengaluru after a wedding in their home town.

As he tried to stand up, a searing pain shot through his legs and forced him down again. Someone tried to hold him as he sank down. That fateful evening seven years ago changed Prajwal’s life — a car coming from the opposite direction had collided into their motorbike. As some construction workers from a nearby building site rushed to their aid while they waited for help, Prajwal recalls being scared and shocked.

“The labourers gave us water,” he tells Weekend Review. “Then they convinced an auto driver to take us to the nearest government hospital.”

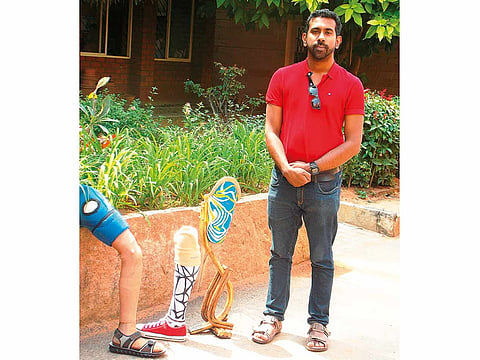

A Rise Legs employee, Basayyah works on a cane prosthesis model. Mythily Ramachandran

En route, crawling traffic prolonged their misery by another four hours. When they eventually reached the hospital, it was past 9pm. “Initially I was quite calm and the doctors did not think anything was serious with my condition,” he says.

But the doctors soon found that Prajwal had broken his left femur bone and the nerves of the leg were destroyed beyond repair. He had to be moved to a private hospital for further treatment. Three major surgeries followed before his left leg was amputated above the knee. For the avid sportsman who played in the college cricket team, a kabaddi and kho-kho player at district level, the dream of a sports career ended that night.

However, Prajwal moved on and despite his amputated leg, made remarkable strides. The 26-year-old fitness trainer works as a gym manager in the city now. Besides walking independently, he rides a scooter too. After winning the Mr Karnataka title in 2016, he added another feather to his cap when he finished as the fastest contestant in the obstacles event at Cybathalon 2016 — a unique championship for disabled people that’s held in Zurich. Now Prajwal is an inspiration to many who find themselves in a similar predicament.

What makes Prajwal’s life easy and normal is the new prosthesis made of cane — yes, the same material used in furniture. This innovation is the brainchild of engineer turned social entrepreneur, Arun Cherian, who set up Rise Legs to develop the prosthesis.

Before Prajwal met Cherian, he was using the Jaipur Foot, a prosthesis designed by Ram Chander Sharma in 1968. Besides being heavy, the Jaipur Foot caused abrasions through continuous wear. “I had to remove it frequently,” explains Prajwal. “Climbing slopes was difficult with [the] Jaipur Foot.”

For the past two years he has been using the Rise Legs model. Comfortable and pain free, Prajwal balances himself well on every kind of terrain, and he surprised Cherian wearing it to jump off walls up to two-metres’ high during trials for Cybathalon.

“I have tried to break it many times but in vain,” Prajwal laughs.

Since its inception in 2015, Cherian has fitted about a 100 amputees with Rise Legs, and his customers come from different parts of India and belong to different walks of society.

“It’s amazing how people have chosen us over Ottobach — a German company — and Endolite from the United Kingdom,” Cherian says. “My aim is not to fit a million amputees with legs but to get a million people smiling and to empower them.”

Cherian’s relationship with his customer continues long after fitting them with Rise Legs, and each leg is customised depending on the customer’s requirements. “It’s not like a shoe you buy and forget. It’s more like buying a car. Customers must come for servicing.”

After the initial fitting, the body will change so the prosthesis has to be adapted accordingly. Regular follow-ups are needed, and Cherian says he only entertains customers who can come for these sessions.

He never intended to become an entrepreneur. The mechanical engineer was working on his PhD at Purdue University but he had an epiphany during a short break in Kerala to attend his sister’s wedding. Sitting on a cane chair at home, he pondered over the possibility of using cane to make prostheses.

“It was really a curiosity-based question,” remembers Cherian, who specialised in bio-mechanics of locomotion at Berkley. He used to make robots that could walk on land and go into the water and swim, exoskeletal suits that paralysed people wore to enable them to walk. “If cane can be bent into different shapes for furniture and can take weight, can I make a leg out of it?” he wondered.

Cherian delved into research on cane and met a local cane craftsman and cane suppliers. His study involved examining numerous species of cane and, after a year, zeroed on to one particular species — still a trade secret today. Taking a metre-long cane, he tested it for rigidity and elasticity at IISc in Bengaluru and the Indian Institute of Space Science Technology in Trivandrum.

“I compressed it so much that the machine ran out of space, and when compressed further by 25cm, it did not break,” Cherian recalls. Designing a leg out of it, he tested it again in the same machine. “We were behind a protective screen and my heart was in my mouth, wondering when it will snap but it turned way better than that.”

Cherian remembers trying to kill the idea in the first year so that he could move on. “I was not married to the idea that this is brilliant,” he says. “Design fixation is not a good thing because you might end up shoving a bad idea to people.”

But cane was not going to let him go easily. He put out a call for people to test the leg.

Madhusudhan, a bilateral amputee with prosthesis and walking with crutches was the first recipient of the Rise Leg. After failure tests and alignment issues were corrected, on the third day Madhusudhan walked using Rise Legs without crutches.

“On the fifth day he kicked a ball,” Cherian recalls, and soon Madhusudhan could walk kilometres independently.

Water, however, presented a major stumbling block. A drizzle did not affect it but when Prajwal went to the beach and soaked his leg in water, its shape got warped. The leg also failed a farmer because he worked long hours in his paddy fields. Parveen, another user, suffered when he was stranded on the streets during Bengaluru’s floods.

The problem, however, was solved by using multiple layers of water-resistant materials. The next hurdle came with the making of sockets — the space into which the stump of the amputated leg sits.

“We don’t have qualified prosthetic technicians to make sockets that are customised,” Cherian says. “The traditional method of using plaster of Paris for making the cast is cumbersome and risky while transporting.” This was solved by digital scanning technology, with the cast then digitally carved using carbon fibre or medical-grade plastic.

Cherian says the technology is cost effective and a pilot trial is being run in association with International Red Cross Society in five cities in India.

The central cane structure is fitted with knee joints, depending on the user’s requirement — ranging from the basic to one that allows walking over uneven streets and climbing steps. The high-end joints are for those who indulge in sporting activities. The prosthesis is covered externally in skin tone-finish in 28 colours or art designs

“We are the only one making digitially printed skin texture, matching the customer’s skin tone,” Cherian says. “Cosmetic features can be removed to make it affordable. No one walks away without a leg.”

Cherian considers Madhusudhan one of the hardest cases to work on. “It was the initial years when I was trying to understand cane after having worked with titanium and robots.” He is proud too of Prajwal who uses the same prosthesis for all activities. “It’s not like he uses one for sports and another for regular use,” he says

Rise Legs grew as a start-up company with funds from friends and relatives. A table at the Association of People with Disability in Bengaluru served as a working unit, and in 2016, MIT-D Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology supported Cherian under its Scale Ups Fellowships.

He’s in discussions with a prominent German automotive company on expansion plans, first in south India and then across the sub-contintent. The next step will be reaching out to countries including Kenya, Ecuador and Afghanistan.

For Cherian, who quit his PhD to concentrate on Rise Legs, the odyssey has been one of self-discovery. After working with robots worth $120,000 and nickel and titanium, he chose to work with cane which costs less than $10 for a basic structure.

Cane, being a creeper, does not take its own weight and is very uniform in cross section. “It makes great engineering material,” he says. Out of 1,500 species of cane, I use just one particular kind.”

“I want people to run and dance and more — not just walk with Rise Legs,” Cherian says.

Mythily Ramachandran is a writer based in Chennai, India.