A.R. Rahman's music without borders

Oscar winner opens up about his philosophy and shuttling between LA and Chennai creating universal music

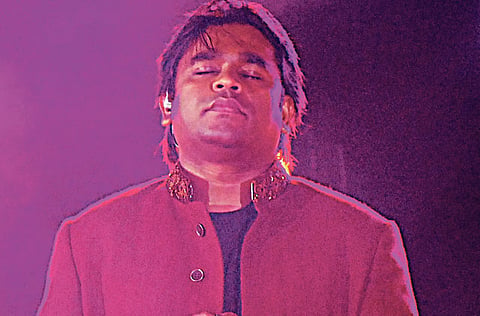

There is a certain divinity associated with him. Be it his name — Allah Rakha Rahman — his music or his serene personality.

The musical genius from Chennai, whose footprint has widened globally following two Oscars for Slumdog Millionaire, floored me with his ethereal human side when I met him ahead of his concert in Muscat on Thursday.

Rahman is an international star, but one that is grounded and completely at peace with himself and his music — something he says is his soul and life. "There's nothing beside music about me," the maestro from India told tabloid!

The shy son of film composer R. K. Shekhar, Rahman is not a man of many words, but those about his music evoke instant and enthusiastic responses while questions about politics or religion distract him a bit. He simply ducks every attempt to evoke negative comments and does not easily show his own dislikes, even when he talks about controversial topics.

"Nobody held a gun to my head and said, ‘you have to sing'." Rahman's statement may sound agitated, but in fact he was as calm as ever in answering this question on the controversy, in India, about singing the national song Vande Mataram (I bow to motherland).

"No one should be pressurised to sing [Vande Mataram]," he says in the second breath. He, however, insisted that he sang on his own will, still sings and would continue to sing. "Because my understanding of the religion is different."

India's right-wing political party Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) wanted to make it mandatory in schools for children to sing the national song while some Islamic organisations objected, terming it to be against Islam.

Rahman calmly made his point, which favoured neither the BJP nor the Islamic organisations objecting to singing Vande Mataram.

Rahman makes his point with conviction. A devout Muslim, he regrets that Islam is equated with violence in some quarters, especially after 9/11. "I would say that Islam is about mercy if taken in right perspective." Otherwise, he points out, every other faith has had violence too.

"Christianity has seen violence, Buddhism has seen violence, human beings are cruel, but there are good people and bad people," he said when pressed on the topic.

"So probably even in Islam there are some bad people, some good people — but you can't call Islam bad," he insisted, adding, "complicated question, complicated answer."

Two worlds

Rahman, who cut his teeth scoring music for Tamil films in southern India, is rather philosophical about his widening workarea — between Chennai and LA.

The two worlds are as different as chalk and cheese. Tamil cinema is loud and fans are passionate about the stars — almost to the point of obsession — even more than in Hollywood. It's interesting to see how Rahman navigates the two filmmaking worlds as he shuttles between the two cities.

"I don't think like that. I go back home [Chennai], I keep meeting the same people, same directors, whom I started with. For me, it is an expansion. [Hollywood] is just an addition. Art has no boundary.

"If you think of [the] good of humanity, it reflects in your music. It applies to life as well. I do not think I am a Tamilian, Hindi. I go there [Chennai] and people welcome you. They love you for what you are. Then you go to London or the US. It is the same.

"I am an open person. How universal love is, it is my philosophy for music too," he enthused. "How they say we all came from one source — that kind of perspective, my music is that. Good music can be listened to by everyone, anywhere."

With his growing popularity and demand, is there work overload? "You first of all plan your timing in such a way that you have enough time," he said.

"If I do 20 movies a year, I might have that kind of problem. I accept very few movies at a time so I can concentrate on [the] work at hand."

Rahman, who is a slave to melody, recently collaborated with Kylie Minogue and the Pussycat Dolls, and says he never wanted to restrict himself to film scores. "That is the way I am made.

"My journey through music is not about film music alone. I was playing in a band, I was involved in things apart from film music. It is 20 years now. You evolve as a musician. I am open to different collaborations."

Can we expect him to be doing rap and hip-hop music or changing his look anytime soon, then?

"Who knows whether I will be alive after five years?" He smiled. "What is today is today — be happy today."

Rahman, a self-confessed studio-man, is famous for working overnight in his studio, so when asked how and when he composes his music, he said: "It is like incubation — you need the right temperature in your brain, the right mindset. If you are too excited or too calm, nothing can happen."

"You need the right space and right frame of mind."

He has lived closed to the sea all his life in Chennai, Does he ever get inspiration from there?

Rahman opened up momentarily and showed his humorous side, "Sea? Not after the tsunami."

Getting serious again, he revealed that he doesn't get inspiration as such to create his music. "I believe music is a blessing, it flows. Music is God's gift."

Music Piracy

Tackling one of the most controversial issues in music today, the over 100-film veteran A.R. Rahman believes that music piracy is an inevitable evil and says it doesn't make him angry. "If you want to get angry, you have to get angry with everything. I get angry, but I know how to control [my anger]. If you don't get angry you are not human."

Concert Review

Jai Ho, Rahman

Oman had never seen anything like the Jai Ho concert before as over 15,000 people packed the Royal Oman Police Stadium on Thursday night to watch Oscar winner A.R. Rahman perform with a troupe of 90 artists.

Drummer par excellence Shiv Mani set the tone for the three-hour show that started on time at 8pm and ended on the stroke of 11pm.

The concert proved that shows of this scale can be held in Muscat and audiences would pay to watch. Massive LED screens made a perfect backdrop as everything worked to precision. Hundreds of lights dazzled the wide stage as the sound quality and 3D projection provided a life-like effect throughout the show.

Rahman was, as usual, most unassuming on stage, but unleashed his vast repertoire of songs and demonstrated his ability to handle different instruments, including an unplugged session on a giant pedal piano with Hariharan, Sadhna Sargam, Rashid Ali and Javed Ali.

Rahman let his music take centre stage and did not indulge in costume changes, a la Bollywood shows, but made sure to wear the Omani mussar (headgear) when he got lost singing sufi songs.

If there was a sombre sufi session by Rahman on harmonium while sitting on the floor, then there were peppy hip-hop, pop, reggae, heavy metal, rap and ballads to satiate the eclectic audience.

The audience jumped, danced and whistled with joy throughout the concert and went away with moist eyes as Rahman called it a day with the emotional rendition of the Indian national song Vande Mataram.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox