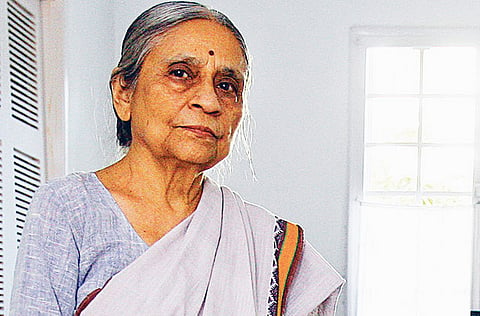

Ela Ramesh Bhatt is leading by example

Ela Bhatthas empowered thousands of women through her organisation SEWA

With the desire to meeting her and visiting her organisation's offices, I had fixed a full day's appointment with Ela Ramesh Bhatt, the founder of the Self Employed Women's Association, or SEWA. I have had the opportunity to meet people from various walks of life but this meeting was different because self-empowerment and liberation of mind and soul were the underlying philosophies behind Bhatt's success and the movement she launched.

In a multi-storey building on the banks of the historic Sabarmati in Ahmedabad in India's Gujarat state, SEWA Bank jostles for attention alongside Banque de Paris. As I enter the bank's office, I am greeted by the sight of women conducting transactions.

But what makes this bank different from the others is that SEWA Bank was set up by women, to help women and is controlled by women. The bank has made history of sorts in the Indian subcontinent, becoming an example of the power of self-reliance and determination..

Gujarat had just begun to find a place for itself on the world map, being the place where India's struggle for independence was flagged off, the philosophy of ahimsa, or non-violence, took root and the historic Dandi March and Satyagraha movement were launched. There, on September 7, 1933, Ela Bhatt was born into a Nagar Brahmin family.

She was to become the torchbearer of the cooperative movement in India and the champion of Gujarat's downtrodden women. History is exciting and fascinating by itself, but when it represents a struggle to assert one's identity and existence, it attains added significance. The organisation that Bhatt set up more than three decades ago employs more than 300,000 rural women today.

Markets do not function without institutions and better institutions help markets run efficiently. Bhatt has built more than 18 innovative and effective market institutions over the past 30 years for the women of India. She is better known as a lawyer by training, trade union leader by position and a Gandhian by her life values.

Her work is awe-inspiring and mammoth in terms of scale, quality and the impact it has made on society. Elaben, as she is often called, has built a business development federation of 86 women's service cooperatives with an annual turnover of more than Rs250 million each, a cooperative savings bank of 200,000 women and an annual turnover of more than Rs6,000 million, a health insurance programme covering more than 100,000 women, a direct-marketing outlet covering more than 35,000 women and many more noteworthy institutions.

Each institution that Bhatt created has made a distinct difference to the economy. SEWA Bank, which she founded in 1974, pumps Rs20 million into Ahmedabad's economy through 3,000 transactions every day. Banas Craft, a direct outlet for artisans, makes spot payments ranging from Rs250 to Rs2,000 to about 1,000 women every day.

SEWA as a movement is unique as it represents the struggle of women to secure the right to voice their opinions and demand work, justice, proper wages and recognition and, above all, to be given a proper place in society as equal contributors to the economy.

India is a populous country with the distinction of having a female president and has always been in the news for its struggles for independence, cultural change and economic reforms. When India does something, the world sits up and watches, as many times such struggles have contributed to progress in a big way.

In a country where women directly or indirectly contribute to the national economy, protecting their interests and rights has to be taken up on a war footing. SEWA is the largest trade union in India with a membership of 687,000 women. Its members consist of vegetable and garment vendors, in-home seamstresses, headloaders, ragpickers, construction workers, incense-stick makers and agricultural workers. Belonging to India's "unorganised sector", they often have to fight together to secure their dues and rights. Ninety-six per cent of all female workers in India are from this sector.

Among their achievements is the SEWA Bank, whose capital is made up entirely of their own contributions. The SEWA Bank was founded in 1974 by 4,000 women, each contributing Rs10 (less than Dh1).

The idea of the bank germinated in the mind of the young Bhatt during her days with the Textile Labour Association but ultimately it had to find its own footing as the association itself did not open-heartedly support her idea. "It was not easy for me to start SEWA. In 1972, we started organising and unionising self-employed female workers. And it took many years to get ready for that stage [when the bank could be launched].

"The road was not so easy because the registrar of trade unions asked: ‘How can you call it a trade union? Who is the employer? Against whom are you going to fight?' I argued that a union was not meant only to fight or oppose but also to work towards achieving other aims — and that was to bring about changes in many laws and policies. Women [in the unorganised sector] may not be able to pinpoint an employer but they have to fight against certain systems. Like the contract system. Or the series of middlemen, contractors, subcontractors and sub-subcontractors. It is an exploitative system," Bhatt says.

From the beginning, Bhatt realised that communication was key to organising workers at the grassroots level. Changes at the macro level had to percolate. Similarly, whatever happened at the grass roots had to be conveyed to agencies at the national and international levels.

Bhatt's communication skills and perseverance supported and kindled hope and aspiration in thousands of women who believed that they could decide their future themselves.

"I strongly believe in Gandhi's principle that the human being is at the centre of all developmental processes. His values of truth, peace and non-violence were non-negotiable and these helped truth and justice triumph. He also taught us to believe that women are natural leaders," Bhatt says. "Women bring about change and their ability to adapt and multitask is second to none. I have witnessed the power of women in transforming arid desert ecology, stopping migration, reviving the economy and bringing about social change by working together."

Bhatt was one of the first Indians to realise the potential that global markets held for women working in small and micro-businesses. She founded Women's World Banking and set up a global federation of vending and trade businesses in 11 countries called Street Net to provide access to markets through policy and legal interventions in favour of women.

Bhatt's work has brought her many prizes, including the Magsaysay and the Right Livelihood awards. She has been invited to speak at conventions and universities across the globe. Her work in building women-driven market institutions has earned her top Indian honours such as the Padma Shri and the Padma Bhushan. She has been a member of India's Planning Commission and has been nominated to the Rajya Sabha, the upper house of the Indian parliament. Universities such as Harvard and Yale have awarded her doctorate degrees. Bhatt says such recognition is a testimony to the spirit of women and SEWA.

"I believe capital formation at the grassroots level is a must for women to gain equal access and stake in building national wealth. The institutions that I and my fellow women workers have built are generating surpluses and are sustainable," Bhatt says. "India got political freedom in 1947. But a second freedom will be achieved only when the poor get economic empowerment. The millions of workers who go undocumented and unrecognised form the ‘people sector' — they are neither in the private nor the public sector. Sometimes I am asked: ‘Is SEWA pro-state or pro-market?' I say SEWA is pro-poor.'

SEWA Bank is proof that necessity is the mother of invention. Initially, SEWA members were assisted in obtaining loans from banks but they faced many difficulties. So 2,000 SEWA members held a meeting, raised Rs100,000 in a few months and decided to start a SEWA cooperative bank. Today the bank has a sizeable working capital and 200,000 members borrow from and save with it.

Bhatt's charisma has been strong enough to attract highly qualified professionals such as Renana Jhabwala (daughter of the celebrated Ruth Prawer Jhabwala of Ivory Merchant Productions) and Jayshree Vyas, who gave up lucrative corporate careers to join Bhatt in her mission to lead women to economic independence.

Vyas, the managing director of SEWA Bank says: "Women constitute a major demographic in society and SEWA has given them a sense of belonging and ownership. All our policies are formulated by women. Agencies such as McKinsey consult with us. IIM-A graduates study our model, which is credible as it affirms the quality of work that we have been doing.

"Our work at SEWA is not confined to money: We talk to women on health and insurance and explain the benefits of utilising the money they borrow. Illiteracy is a disease that SEWA has been fighting with great gusto.

"One of the qualifications required to start a bank was that the women should at least know how to sign their name. Bhatt took upon that task as a personal challenge and urged the illiterate women to learn to sign their names if they wanted a bank for themselves. Today we find entire generations of women banking with SEWA. The empowerment is tremendous. They save money every day, deposit it in the bank and operate ATMs."

As with couples in partnership for profession and for life, Bhatt's late husband Ramesh supported his wife in her mission, ideas, ideals, projects and schemes. Bhatt has dedicated her wonderful book We are Poor but So Many to Ramesh, who was her friend and philosopher. Theirs was a love marriage in which both understood each other's emotional needs.

Bhatt fondly says of Ramesh: "My husband opened my eyes to the world. He was completely at ease dealing with slum dwellers and their problems, whereas I found it difficult to move out of my shell. I felt frustrated, unhappy and mentally paralysed that I was unable to step out and see how the other half lived. Ramesh's insights and analysis were critical in developing unconventional strategies for the poor and SEWA. Even if we disagreed, his generosity of spirit allowed me to gain the confidence and the strength to defy norms and chart out a new course."

Ahmedabad has been a city where the division of labour between women and men has always been equal. In fact, it is one of the few cities where you can see women pulling handcarts alongside men in crowded roads. But it took a woman like Bhatt, who championed the cause of the urban poor, ragpickers, vegetable vendors, embroiderers to successfully unite and form an organisation that today stands for professionalism and well-planned policies to safeguard women's interests.

We are Poor but So Many, published by Oxford University Press, is a compelling book that chronicles the trials and tribulations of a woman determined to attain her goal of helping poor, hardworking women by providing them with resources so that they could escape from the clutches of middlemen who believed they had a right to control their work.

Hillary Clinton, who came to know about SEWA during her visits to India, said: "As First Lady, I travelled to India twice to represent the United States. I will never forget my visit in 1995.

In Ahmedabad, I met women availing of micro credit to start their own small businesses and achieve economic self-sufficiency for their families. I was inspired by these hardworking women and moved by their hope for the future of their families and of India."

Bhatt believes in and demonstrates the power of truth and reason and is determined to shape an organisation that stands for the spirit of sewa, which means "service" in Hindi.

She has shown that even in today's materialistic world, it is possible to harbour ideals such as equity and social justice and live a life that values achievement, dignity and happiness.

Jyoti Easwaran is a writer based in Dubai.