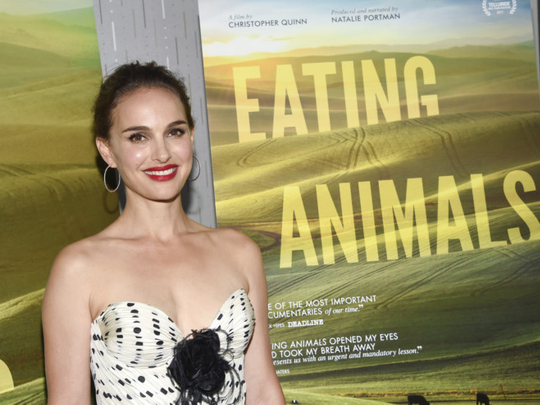

Natalie Portman hasn’t eaten meat since she was nine years old. But it wasn’t until she read Jonathan Safran Foer’s Eating Animals in 2009 that she realised consuming dairy and eggs could harm animals too.

The book struck her so intensely that she instantly called up Foer and told him she thought the project would also work as a documentary. The writer and the actress had been friends for years, striking up a friendship after Portman — then a student at Harvard University — approached Foer after a Cambridge, Mass., book reading for his 2002 novel Everything Is Illuminated.

It took nearly a decade for the documentary, out now in the US, to come to fruition, along the way picking up financial backing from Twitter co-founders Biz Stone and Ev Williams. Portman, now 37, eventually decided to serve as the film’s narrator, while both she and Foer, 41, share producing credits.

The film focuses on the evils of factory farming, though it doesn’t argue that eating meat is inherently problematic. “This is not a film that is for the vegan abolitionist,” said director Christopher Quinn, best known for his 2006 film about Sudanese refugees, God Grew Tired of Us.

“It’s really for anyone who wants to have an understanding of where their food comes from. And I understand why it’s easier for people to turn away. I was one of them. No one wants a finger-wagging about how you eat. People don’t want to change because our lives our busy and complex. It’s a hard thing to ask of anybody.”

On a rare trip to Los Angeles, Foer and Portman met at one of her favourite vegan restaurants, Crossroads, to discuss Eating Animals.

Natalie, what was it about reading Eating Animals that made you want to become a vegan?

Portman: I think the family part of it was really meaningful to me. I think I was pregnant when I read it, so Jonathan asking himself “What do I feed my children?” really impacted me, because I was going through the same thing. I want to impart my values to my kid, but what’s healthy for them? What helps them? And you are sometimes vegan, right?

Foer: Not really. I try not to think about it in those ways. An analogy I sometimes use is to be honest. I think of myself as an honest person; I try to be honest. But if one were to create an all-or-nothing binary with honesty: Are you an honest person or not an honest person? Most people wouldn’t even know how to answer that question. And if you were forced to answer it, it would start to make you uncomfortable in the way that you approach honesty. If a little white lie is going to undermine this whole identity, then [screw] it, I’ll just tell lies every time there’s an opportunity. A lot of people think about food like that, they really do.

Do people give you grief about the fact that you’re not a vegan?

Foer: I guess, but I don’t think that their approach is right, so it doesn’t really bother me... People that say “Are you really a flexitarian? You do realise that wine is sometimes not vegetarian?” [A flexitarian is one who follows a mostly vegetarian diet but will sometimes eat meat.] Even if those people come from a good place, it’s just not helpful to move the world toward a better place and instead makes people feel defensive and pissed off and condescended to. So when I have a conversation about it, I try to move it away from those kind of lifestyle questions and more toward, “What do you care about? Where do you come from? What’s your family like?”

One of the ironies about the conversation about meat is that people think it’s a drag and it’s actually a really nice conversation that can leave people feeling really good and helpful. The crappy version of it is what happens often in dorm room conversations that I experienced in college: people saying, “Yeah, but I saw that you stepped on an ant or wear a leather belt.” Trying to find the person’s weakness instead of the person’s strength.

Portman: I try to preface it by saying, “Look, it was really hard for me to go from vegetarian to vegan.” I don’t expect anyone to completely change. It doesn’t have to be an identity, it just has to be a consciousness — the same way that you might not want to use plastic bottles as much, but every once in awhile, you’re really thirsty and the only thing you can get is a plastic water bottle so you get it, and you feel kind of bad.

Is it difficult for you to stick to the diet all the time?

Portman: I’m very extremist. I’m kind of like an all-or-nothing person. I love what you’re saying [Jonathan] — I wish I could be that kind of person — but I either do it or don’t. I don’t have many in betweens.

Foer: I wish I could be that way.

Why is farming — and raising animals, in particular — thought of as such a deeply American practice?

Foer: Sometimes, there’s an inversion of values in the language, like “Make America Great Again.” If we could only return to being something that we never were, then we will reclaim a kind of pride. We’ve always been a country that cares about farmers and animals in a way that’s unusual in the world. I think a lot of it is religious values — ideas of dominion over animals and the planet. Factory farming is a perversion of those values, and a movement away from factory farming is a return to those values. Even though it often sounds like vegetarianism is some newfangled, hippie-ish, kind of progressive thing, it’s actually conservative. That’s, in a way, the joke behind all of this.

The whole problem is, if you ask people “can you describe what a farm looks like?,” most people would say, “There’s grass, a farmer wearing overalls; he’s got a pitchfork; there’s a barn, animals walking around; the animals probably have names.” And that just doesn’t exist — or it’s far less than one per cent of what exists.

Can you realistically imagine an America where there’s far less meat consumption?

Foer: On high school and college campuses, vegetarianism and veganism is an aspirational identity and has a political force behind it. It’s not so hard for me to imagine colleges flipping what’s normal. Right now, in cafeterias they serve five meat options and a veggie option. It’s not impossible to imagine it flipping so that vegetarian becomes the default. One thing we’ve definitely seen in the last five years is how an extremely vocal and energised group of people who can access social media can reframe a conversation. When we think about the #MeToo movement, it’s not the case that the majority of Americans woke up and realised we had this systemic problem. It’s that people who were very smart about how to articulate the problem and disseminate those articulations pulled everybody with them.

Natalie, you’ve been very active in Time’s Up since its inception last fall. What’s the latest on the organisation’s efforts?

Portman: It’s a new organisation, so we’re still trying to organise. We need to create roles and a chain of decision making — so we’re in that kind of phase. We meet a few times a month, and then there’s an executive committee that I am not on that is meeting more regularly and doing the daily work. It’s definitely challenging, and we’re lucky to be in a place where we can have these conversations and keep trying to make it weird for people to live with the status quo. That’s the goal: To make it culturally weird to stay the way things are.