James Franco: Why actors act out

He takes an empathetic view of the recent erratic actions of Shia LaBeouf

The recent erratic behaviour of Shia LaBeouf, the 27-year-old actor best known as the star of the Transformers movies, has sent the press into a feeding frenzy. Though the wisdom of some of his actions may seem questionable, as an actor and artist I’m inclined to take an empathetic view of his conduct.

Let’s review the facts. First, in December, LaBeouf was accused of plagiarism after critics noted similarities between Howard Cantour.com, a short film he created, and a story by the graphic novelist Daniel Clowes. Though LaBeouf apologised on Twitter, conceding that he had “neglected to follow proper accreditation,” it turned out that the apology itself appropriated someone else’s writing. Was that clever or pathological?

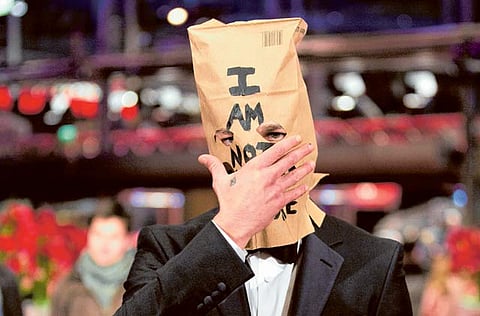

Then, earlier this month, with these actions focusing the tabloid gaze on him, he wore a paper bag over his head that read “I am not famous anymore” at the red-carpet premiere of his latest movie, Nymphomaniac. And last week he staged an art show called #IAmSorry that involved having him sit opposite visitors to a Los Angeles gallery while he wore a similar bag over his head and stared at them through cutout eye holes.

This behaviour could be a sign of many things, from a nervous breakdown to mere youthful recklessness. For LaBeouf’s sake I hope it is nothing serious. Indeed I hope — and, yes, I know that this idea has pretentious or just plain ridiculous overtones — that his actions are intended as a piece of performance art, one in which a young man in a very public profession tries to reclaim his public persona.

Actors have been lashing out against their profession and its grip on their public images since at least Marlon Brando. Brando’s performances revolutionised American acting precisely because he didn’t seem to be “performing,” in the sense that he wasn’t putting something on as much as he was being. Off-screen he defied the studio system’s control over his image, allowing his weight to fluctuate, choosing roles that were considered beneath him and turning down the Oscar for best actor in 1973. These were acts of rebellion against an industry that practically forces an actor to identify with his persona while at the same time repeatedly wresting it from him.

At times I have felt the need to dissociate myself from my work and public image. In 2009, when I joined the soap opera General Hospital at the same time as I was working on films that would receive Oscar nominations and other critical acclaim, my decision was in part an effort to jar expectations of what a film actor does and to undermine the tacit — or not so tacit — hierarchy of entertainment.

Uncomfortable position

As an actor, you are often in the uncomfortable position of being the most visible part of a project while having the least amount of say over its final form. In one of the most striking scenes in I’m Still Here, a 2010 film co-written by Joaquin Phoenix that purported to document his life as he retired from acting and became a hip-hop artist, Phoenix paced around his yard at night, ranting about the submissiveness of being an actor. Even if the conceit was ultimately a joke (and initially it wasn’t clear that it was, for Phoenix stayed in character in public throughout the filming), the movie was nonetheless earnest about an actor’s need to take back a little bit of power over his image by making such a film.

Any artist, regardless of his field, can experience distance between his true self and his public persona. But because film actors typically experience fame in greater measure, our personas can feel at the mercy of forces far beyond our control. Our rebellion against the hand that feeds us can instigate a frenzy of commentary that sets in motion a feedback loop: acting out, followed by negative publicity, followed by acting out in response to that publicity, followed by more publicity, and so on.

Participating in this call and response is a kind of critique, a way to show up the media by allowing their oversize responses to essentially trivial actions to reveal the emptiness of their raison d’etre. Believe me, this game of peek-a-boo can be very addictive.

LaBeouf has been acting since he was a child, and often an actor’s need to tear down the public creation that constrains him occurs during the transition from young man to adult. I think LaBeouf’s project, if it is a project, is a worthy one. I just hope that he is careful not to use up all the goodwill he has gained as an actor in order to show us that he is an artist.

— James Franco is an actor