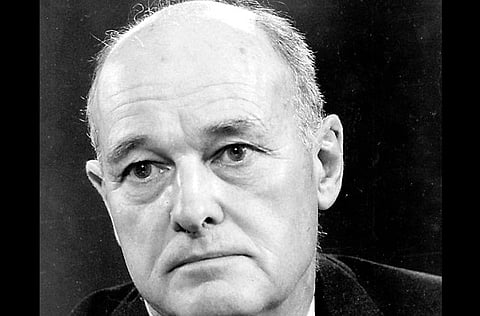

America's foreign affairs expert

An excellent analyst, George F. Kennan offered sensitive and farsighted vision which often went straight up the State Department policy

At the end of the Second World War, the United States, the emerging superpower, took some time to realise that it had been fooled by Joseph Stalin's USSR. The two countries fought Nazi Germany together, but after the victory, the USSR grabbed as much territory as it could and refused to concede any to its allies.

After the war, which had thrown the whole of Europe into confusion, the US continued its wartime diplomacy as it held the view that Stalin had abandoned centuries of Russian history and was working towards peaceful coexistence with the rest of Europe and the US.

At this crucial moment, the State Department asked its Moscow embassy to comment on a routine speech by Stalin. The ambassador happened to be away, so the deputy ambassador, George F. Kennan, took the opportunity to write the now-famous Long Telegram, in which he demolished his government's assumption that the USSR was friendly, arguing effectively that the Bolsheviks had taken Russia's deep distrust of the outside world, to which they had added their own global revolutionary doctrine.

But Kennan went a vital step further and predicted that the USSR and the Communist Bloc would collapse of its own accord, unable to manage the vast territories it had acquired, nor the command and control economy that it was building. But he had no doubt that the US was facing a serious enemy: The Soviet leadership controls vast natural resources and "the energies of one of the world's greatest peoples", Kennan wrote. This will "undoubtedly be the greatest task our diplomacy has ever faced".

Kennan's solution was to invent the concept of "containment", which became the heart of US foreign policy for half a century. This meant that the US did not need to go to war with the USSR, but nor did it need to continue to accept it as an ally. Kennan continued his argument in an anonymous article in the influential journal Foreign Affairs. Since he was a serving State Department official, he did not put his name to it, but simply signed it "X". However, within weeks his identity as the author was discovered. This meant that the "X" article was taken as setting out the position of the US, which caused huge controversy. Kennan argued that victory over the USSR (which was still an ally at the time) would not come on the battlefield, nor by diplomacy, but by implosion of the Soviet system.

In his review in the New York Times of George F. Kennan, An American Life, a later master of foreign affairs, Henry Kissinger commented that no document forecast so presciently what would in fact occur under Michail Gorbachev four decades later. Kennan was an excellent analyst, offering sensitive and farsighted vision which often went straight up the State Department policy and over to the White House to become official American policy with very little debate. But Kissinger also made the interesting comment that while his vision was exceptional, Kennan blighted his career in the government by a tendency to recoil from the implications of his own views. The debate in America between idealism (foreign policy based on universal principles) and realism (foreign policy based on national interest) which continues to this day, "played itself out in Kennan's soul", Kissinger said.

John Lewis Gaddis, the distinguished professor of history and strategy at Yale, has written George F, Kennan, An American Life, a 700-page book (with a further 100 pages of notes and indices) which is essential reading for anyone interested in how foreign affairs are conducted. Adjectives such as "magisterial" and "definitive" are routinely applied to this masterful summary of Kennan's very complex life.

Gaddis had complete access to Kennan's private notes and archives, but promised not to write the book until after he died. However, neither Kennan nor Gaddis could have known that Kennan was to be exceptionally long-lived, since he eventually died aged 101 in 2005.

Kennan's most effective period was in the Truman administration, when he used the State Department's new Policy Planning Staff to virtually rewrite American foreign policy on almost all areas of activity. But two stints as ambassador (in Moscow and Cuba) ended in embarrassment and he moved on to academia, from where he was a regular and valued commentator on events, focusing on how particular moments would fit into the broad sweep of history. A sense of frustration seems to break though in his later writing, as Kennan wanted to put his ideas into action.

But such a clear analyst of foreign affairs cannot be confined to a particular moment in history. Reading Gaddis's biography with his own analysis of Kennan's ideas is important for anyone thinking about how the current confrontation with Iran might be managed. Kennan never saw containment as a purely military option, and was furious with the way the White House of the 1950s and 1960s perverted his idea into a military solution. He argued that containment means engaging the enemy over the whole range of human experience, including economic activity, which might include sanctions but would also include using trade to subvert a regime, and cultural activity to destroy an enemy's moral basis.

As Gaddis writes, Kennan "regarded successful containment not an end in itself but a prerequisite for the ultimate process of negotiations".

George F. Kennan: An American Life By John Lewis Gaddis, Penguin Press, 800 pages, £30