Danish artist gave a museum empty frames. Why it's more than just a stunt.

Danish court ordered Haaning to repay about $70,000 to make up for'deficient performance'

A few years ago, Danish artist Jens Haaning, 57, was growing frustrated with the cost of preparing a museum commission. After a bad car accident took Haaning off the road, he had to hire a driver to take him to Berlin and quarantine in a hotel for a week because of covid restrictions - all to frame the artworks there for an exhibition.

"Suddenly, the expenses carried on my shoulders got bigger and bigger," Haaning said in an interview with The Washington Post. He found it "completely unfair that I need to come up with money in my pocket to go to work."

The situation was particularly ironic, Haaning notes, because the pieces were intended for a 2021 exhibition at the Kunsten Museum of Modern Art Aalborg about labor. The artworks he was re-creating - "An Average Austrian Annual Income" and "An Average Danish Annual Income," first exhibited in 2010 and 2007 - consisted of those countries' mean salaries, displayed in hard cash. The museum lent him the equivalent of $84,000 at the time on the condition that he would return it.

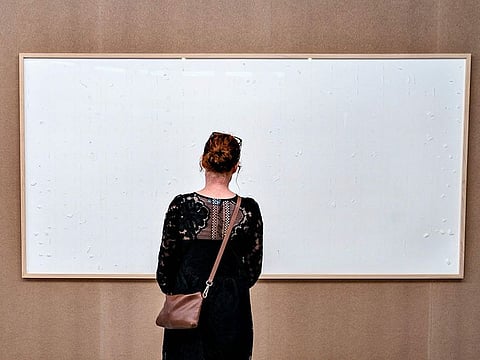

Haaning, instead, decided to give himself a salary to "Take the Money and Run," as the work's title makes clear. He sent the museum two large empty frames and deposited in his bank account the equivalent of tens of thousands of dollars, which he used for groceries and bills. "I didn't do anything extraordinary," he told The Post.

Not repaying the museum is part of the art, he has said.

Now the museum wants its money back. A Danish court Monday ordered Haaning to repay 492,549 Danish kroner (about $70,000) to make up for his "deficient performance," raising questions about the fuzzy line between con and commentary, and whether Haaning was breaking the law - or just breaking boundaries.

The museum declined to comment on the case and Haaning's expenses during the four-week appeal period.

There's an overused criticism people tend to level against contemporary art: "I could do that," they say, and Haaning's frames seem to underscore their point. The work deals with "existential" concerns, he argues, which to some, might sound like a high-schooler turning in a blank page for a history essay and saying it's about how history can never be wholly recorded. It seems like a stunt, but is it? And could you really have done it?

Haaning wasn't so sure he could. The artist, whose work has been shown at the Museum of Modern Art PS1 in New York and whose early career was surveyed at Gothenburg International Biennial for Contemporary Art in 2017, mulled the idea for months. "I was thinking, 'You're not going to do that. This is too rude. This is totally against the rules,'" he recalls. "But somehow I had this feeling that it could create a fantastic piece of art."

Despite forging ahead with the lawsuit, the museum didn't necessarily disagree. It displayed the pieces and on its website, described them as "recognition that works of art, despite intentions to the contrary, are part of a capitalist system that values a work based on some arbitrary condition."

But that didn't stop the museum from "conflating the artwork's symbolic and economic value, a distinction that artists have made repeatedly in the past century and a half," Alexander Alberro, an art historian at Barnard College, wrote in an email, calling the whole affair "bizarre."

Haaning's work isn't without precedent. Conceptual art typically deals in the forces that exist beyond the eye, and it can leave you looking at a pile of newspaper, tree trunks, an empty chair or other seemingly banal objects. The point is not what's in front of you, but what the object evokes, the ideas it stirs, the systems it reflects - and sometimes, as in "Take the Money and Run," what isn't there.

Blake Stimson, an art historian at the University of Illinois at Chicago, said the work is both a stunt and an "effective example" of institutional critique, a movement in which interrogating institutions, often museums themselves, is considered an artistic practice.

Stimson traces the approach back to Marcel Duchamp's 1917 "Fountain," in which the artist turned a urinal upside down, signed it and proclaimed it art. He likens Haaning's piece to Hans Haacke's "Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971," which investigated the fraudulent activities of a major New York real estate corporation over two decades.

Both are "focused on the ways in which capitalism's civil contract between worker and employer (in Haaning's case) or tenant and landlord (in Haacke's case) compromises the social contract between citizens," Stimson wrote in an email.

For Haaning, the message he hopes to get across is simple: "If you're participating in something - a religion, a marriage - and the construction is unfair to you, you should maybe consider," he said, trailing off. "Eh, just take the money and run."