On path of economic integration

GCC members have been slow to improve relations in many fields

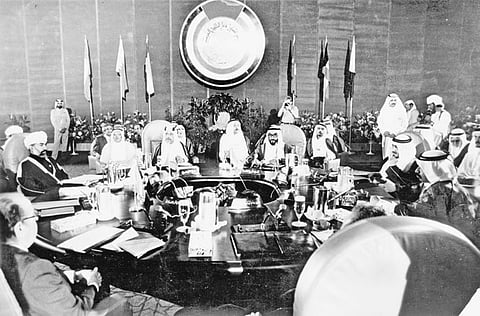

It is a strange coincidence in the 30-year history of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) that its biggest challenges come at the turn of the decade.

The GCC was established in 1981 to protect the states of the Gulf from both perceived and real threats from Iran and Iraq, and the six-country block received its first test exactly a decade later when one of its members, Kuwait, was invaded by neighbouring Iraq.

In 2001 the GCC had to respond to the backlash from the September 11 attacks — as well as the fact that most of the attackers came from Saudi Arabia — and now, in 2011, it is the Arab Spring and response to it that has monopolised the region's attention.

But while the political justifications — and indeed, successes — of the GCC have become increasingly obvious, with financial packages for Oman, Bahrain and Egypt as well as collective mediation in Yemen among the key moves, the economic union of the bloc has always been underplayed.

The original ambition to establish a common currency by 2010 was shelved in early 2009 in a row over where the GCC central bank should be situated, and while limited steps towards a full customs union have been a success, trading volumes between the countries of the Gulf are pathetically low.

The limited successes of the GCC so far also contrast badly with the rapid rise — and success — of the Asean bloc, as well as the European Union. It is a fact, argued Dr N. Janardhan, a UAE-based political analyst, that while in foreign policy the GCC has proved to be an overwhelming success for the region, when it comes to economic unity its achievements are more muted.

"I tend to think that the continuance of the GCC lies in the security rather than the economic sphere. Look at how long it took the EU to come together economically, and then look at how long it has taken the GCC to come this far," he said.

Others feel that to compare the EU and Asean with the GCC is unfair, given how long these unions took to gain strength, and the political will that was needed by leaders of major players to make them to work.

In recent years, said Dr Samir Pradhan, a Doha-based economist, the very public trials of the Eurozone have almost certainly had an impact on the lukewarm attitude of regional policymakers to greater integration.

Integration

"It is amicable to stake benefits during prosperity, but very difficult to share costs during diversity. This must be going through the minds of GCC policymakers," he said.

"It is common that full-fledged regional integration usually takes a longer time frame, as it involves consensus building among partners with sometimes convergent economic interests and divergent political interests."

Pradhan pointed to a number of successes of the GCC over the past decade, including institutional arrangements for negotiations on cross-cutting issues, as well as a liberal visa regime and reformed property investment and ownership rules for GCC citizens.

But he also pointed out that policymakers have got bogged down in other issues in recent years.

"Where GCC lacks is the implementation of rules and procedures both in letter and spirit at the national level in order to enable a level playing field at the regional level. The overall negotiation process could have been faster," he said.

Janardhan goes further. He believes that the areas where the GCC has achieved consensus are relatively minor and, in terms of economic policy, it is yet to be tested on major issues.

Even on one of the biggest successes of the GCC so far, the common customs union, Janardhan said, the issues are far from completely resolved. There remain problems at specific borders, for example transporting gas from Qatar into Kuwait because of Saudi objections.

"It's these kinds of issues that are keeping unity always on tenterhooks," he said. Janardhan added that the issues that have been addressed so far have not sufficiently tested the mettle of GCC leaders. A common customs union, free working rights for GCC nationals and visa-free travel are relatively small fry, and countries lose little from them.

"These are not big-ticket issues, and the stakes are far too low. These are things which bring about benefits for everyone without hurting their individual interests, so they don't mind doing it.

"When it comes to a common currency or a common market, those are the issues that are proving to be very contentious," he said.

Farouk Souza, chief Middle East economist at Citigroup in Dubai, agreed.

"When you think of the GCC as a project, in general you see that since 2003 we have had a customs union — on paper; since 2008 we have had a single market — again, on paper," he said.

"When you actually look at whether or not we have those things, the answer is categorically no."

In light of this pessimism, the question remains whether there is an economic future for the GCC project, or whether it will continue to focus on security and foreign policy issues rather than economic union.

One issue, Janardhan explained, is that by their very nature, GCC countries are competitors. Saudi Arabia's construction market rivals the UAE's and Kuwait's; in terms of aviation, the UAE is dominant, but Qatar, in the shape of Qatar Airways, and Bahrain, in the form of Gulf Air, are also spreading their wings.

Competition

"There has been competition since the beginning, and when you have that competition I don't think coming together makes sense to each one's USP [unique selling point]. I'm not sure how successful they would be as an economic entity," he said.

In light of these challenges, analysts said that talks about including Jordan and Morocco in the GCC union are premature.

"I think it is highly ambitious to talk about that given the tardy pace of negotiations among GCC members. GCC economic integration at the moment is shallow, not deep regional economic integration, so it is premature to speculate about enlargement at this stage to include geographically distant members such as Jordan and Morocco," he said.

The inclusion of these states, coming in the wake of the Arab Spring movement, is thought to be largely political.

An area, which Janardhan was keen to stress, where the GCC has kept most of its focus.

He points to the UAE-Saudi force deployed in Bahrain, as well as the $20 billion (Dh73.4 billion) fund announced to help Bahrain and Oman cope with their economic and political crises and continued mediatory efforts in Yemen as examples of the GCC operating as a powerful and useful body in the region.

The GCC has also been instrumental in protecting the interests of smaller countries such as Qatar, Bahrain and Kuwait. In the future, it will be relations with Iran that will force the GCC to continue its dialogue.

Pradhan, meanwhile, feels that it is early days. "The Eurozone and Asean took 42 years to become the two most successful regional economic blocs. The GCC is still a work in progress," he said.