Sana'a, Yemen: A doctor would have recognised the signs of chronic malnutrition immediately in the 7-month-old girl — the swollen stomach, the constant cough. Her mother, though, had only traditional healers to turn to in her mountain village, and they told her to stop breastfeeding.

Her milk had spoiled, they said. Their solution: stuff the baby's nose with ghee.

When that didn't work, the young Yemeni mother, Sayeda Al Wadei, made the arduous 96km journey through the mountains to the closest hospital with facilities to treat her daughter, in the capital Sana'a.

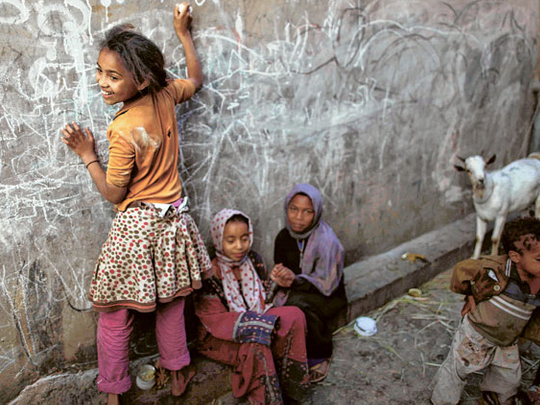

More than 50 per cent of Yemen's children are malnourished, rivalling war zones like Sudan's Darfur and parts of sub-Saharan Africa. That's just one of many worrying statistics in Yemen.

Nearly half the population lives below the poverty line of $2 (Dh7.34) a day and doesn't have access to proper sanitation. Less than a tenth of the roads are paved. Water is running out. Tens of thousands have been displaced from their homes by conflict, flooding into cities. The government is riddled with corruption, has little control outside the capital, and its main source of income — oil — could run dry in a decade.

As a result, Al Qaida is far down on a long list of worries for most Yemenis, even as the United States presses the government to step up its fight against the terror network's affiliate here.

Donor nations are meeting in February in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia to gather millions of dollars for development in Yemen. Aid groups, economists and officials are scurrying to develop poverty reduction and economic restructuring plans for this nation of 23 million.

The United States has already dedicated $150 million in development money, alongside its counter-terrorism aid to fight Al Qaida, which is to grow from $150 million to $250 million over the next year. Other donor countries have given millions more, acknowledging that the terror network cannot be uprooted unless Yemen is pulled out of poverty.

"The neighbouring countries and Europeans and US have a lot of stake, not only in Yemen, but in the Middle East. I don't think anyone wants to see Yemen failing," said Benson Ateng, the World Bank's Yemen country manager.

Some aid workers fear that the government, which clings to power through patronage, will direct aid to allied tribes while leaving others out in the cold, fuelling resentment. A focus by donors on steering aid to areas with a known Al Qaida presence, not necessarily the poorest zones, may also backfire.

"Donors are focusing on development as a tool to address security issues, and not as an end in itself," said Ashley Clements, Oxfam representative in Sana'a. "There is a risk that the tendency will increase over the years. Focusing on one issue alone will be to the detriment of the well-being of Yemen's people."

Malnutrition typifies how overlapping problems lead to crisis. Much of Yemen's agriculture — and 30 per cent of its water — has turned to cultivating qat, the mildly stimulating leaf that Yemenis addictively chew, leaving the country a net food importer with little cash to pay for it. At the same time, health infrastructure and education is lacking, the rate of breastfeeding for children under six months is only 10 per cent.

Moreover, the rise in malnutrition was able to pass largely unnoticed because the weak government was not keeping valid statistics and had no commitment or ability to head it off.

"There is no single other country in the world where we ever have seen such high levels of malnutrition," said Greet Cappelaera, Yemen country director of Unicef.

Resources strained

At the Sana'a hospital, Al Wadei's daughter Maram has recovered after treatment. But another of her four children — a 2 1/2-year-old daughter — can barely stand, another malnutrition symptom, and the family can't afford to treat her.

"I don't want kids any more," mourns Al Wadei. "I don't even want myself."

Yemeni officials say their resources are strained by security challenges, including a northern rebellion, a southern separatist movement and Al Qaida.

"If there is no security and stability, there will be no development, no poverty alleviation and no investment," said Hesham Sharaf, deputy minister of planning and international cooperation.

Oil revenues make up at least three-quarters of the government budget, but oil production is steadily declining. Yemen could become a net importer in the next five years and its oil reserves could run out completely by 2021, according to IMF and World Bank estimates.

What development there is in Yemen is a patchwork, depending on where the government has thrown its limited cash. Oil money has fuelled a consumption boom among a small slice of the population. In Sana'a, new hotels and restaurants have arisen, along with shopping complexes boasting Baskin Robbins branches and Porsche and BMW dealerships. Large video billboards advertise new housing projects.

But just beyond the capital's edge, rural Yemen immediately emerges, with little infrastructure. Donkey carts replace SUVs, and government authority largely vanishes, replaced by highly independent local tribes.

In Wadi Dhaher, a village just 10km outside Sana'a, floods have left mud houses partially demolished and deserted. Muddy roads lead to the village's qat plantations, which consumes most of the village water.

For water, Wadi Dhaher relies on a local well dug 400 metres deep to search for disappearing ground water, despite a national law limiting wells to 60 metres to prevent over consumption. Its residents belong to the Hashed tribe, which is nominally pro-government but brooks little interference from authorities. "We are self-sufficient here," said Abdullah Muhsen, a 27-year-old who operates the village bath. "Our authority is the [tribal] shaikh. Even the president needs his approval."

Population growth

In a country with the seventh highest population growth in the world — 2.9 per cent a year — the tens of thousands of Yemenis entering the workforce each year find few opportunities. Many pour into Sana'a for jobs.

Mourad Hamoud dropped out of high school in the southern town of Taiz and moved to Sana'a, hoping for a government job. But he found such jobs go mainly to northerners, so he opened a barber shop. "I couldn't keep up with studying and working," he said. "If things were right, I wouldn't have to leave studying to work."