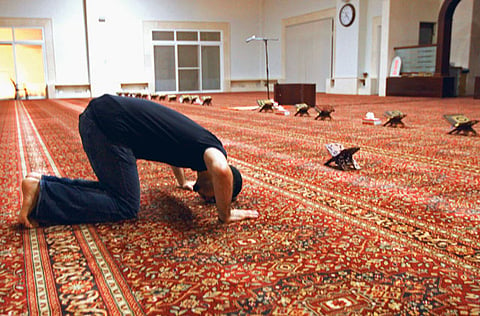

Religious conversion, a social taboo?

In the Arab world, community pressure and politics make changing religion a contentious issue

Dubai: When Ganem left Kuwait to go to the American University of Beirut (AUB), the last thing he expected was to embrace Islam.

Ganem, 29, grew up in a Christian Lebanese household in Kuwait. Most of his friends were Muslim, but he admits to not knowing much about the religion. He would party and drink with his friends. Religion was not a topic of conversation. But for Ganem, something was missing in his life that led him onto a path that is nearly unheard of in the Arab world — conversion.

"My parents raised me to be respectful of religions, and while growing up Islam was never a problem, until I became Muslim," Ganem explains.

Ganem was constantly soul searching during his years at AUB until he decided to read about Islam one day. It wasn't until his junior year, after researching Islam for almost a year, that he decided to become a Muslim.

Ganem felt confident to discuss his embracing of the religion with his parents, because after all, he had a fairly liberal upbringing where religious tolerance was ingrained in him.

"Initially my parents thought it was just a phase. One day, however, my Dad came into my room and saw a stack of books about Islam, and flipped out," Ganem recalls. "He thought I was being brainwashed, and told me to throw the books away."

Fears

His siblings were afraid he was on the path to becoming a militant or fanatic, Ganem says. "But soon they realised I was the same person. I was just happier and didn't drink or go clubbing."

Ganem's family is part of Hezb Al Qomi, an ideology popular with many Arabs that espouses pan-Arabism. In this ideology, Arabness supercedes religious identity.

Growing up in Kuwait, however, Ganem's family was affected by some extremists.

"The intolerance by some Muslims against non-Muslims contributed to my parents' ideas about Islam, as well as the Western media which often portrays Muslims as fanatics," he says.

Ganem is among a very small percentage of Arabs living in the Middle East that embrace a new religion. When asked to explain why he thinks conversions are uncommon, Ganem says it boils down to tradition.

"Arabs stay close to their traditions and upbringing. Religion falls under tradition. When you reject your religion, you are rejecting your upbringing and that is a big deal for Arabs."

Rima Sabban, a Sociology professor at Zayed University, echoes Ganem's sentiments.

"Arab society is very family and community based. We want to cling to who we are and it is not easy to abandon. It is less about beliefs and more about identity," she says.

"The West focuses more on individualism, which could explain why conversions are less taboo, but in the Arab world rejecting one's religion is rejecting your origins and who you are."

Politics also plays a role, according to Paul Tabar, an associate professor of sociology at the Lebanese American University. In most Arab countries, "religious identity is part and parcel of the political structure," Tabar explains.

"These identities become so important to political allegiances. If you shift identities you shift allegiances, which affects the regime," he says. "In the West, religious identities are less politicised. This gives people more breathing room to embrace a religion," he added.

In Lebanon, a country that was torn apart in the 70s and 80s by a gruelling civil war, religious identity is a very sensitive matter and critical to the power structure. After the war, and the signing of the Taif agreement, the government was again formed under a confessional system where power is distributed by religion and sect; usually to the benefit of the established or aspiring elite.

Religious affiliation is encoded on the Ikhraj Qaid, a document that can serve as a sort of identity card, which indicates personal status information. It can be used when a person is applying to work for the government or employed at a university.

Marriage

Also, inter-religious marriage is not performed in Lebanon. Many couples of different sects who do not want to convert have to get a civil marriage outside the country. Many of them travel to nearby Cyprus.

"Although Lebanese law recognises their civil marriage, the consequences of the marriage are problematic. Personal status issues such as inheritance, adoption or divorce are all determined by laws set by religious authorities of different sects," Dr Sami Ofeish, Associate Professor of Political Science at University of Balamand in Lebanon explains.

"Conversion was relatively more practised in the past, but since the sectarian system that had its founding roots in the mid-19th century developed in Lebanon since independence in 1943 as a major tool of state rule it has impeded integration," he says.

Sectarian communities

"Many people find themselves interested in affiliating themselves with their sectarian communities in a show of identity because they believe that such an attachment will preserve their perceived privileges and those of their community or end their deprivation and that of their community," he adds.

"It doesn't mean that sectarian people are necessarily practising their religious beliefs and rituals but rather it is the politicised use of religion for what they consider promotes their own interests."

In fact, most times the topic is best left alone. Many Arabs openly admit to avoiding the subject altogether, for whatever the reason may be.

"We grew up side by side, but we don't discuss religion," Yousuf, a Palestinian Christian explains.

Ayad, a Muslim Iraqi, agrees.

"We are an emotionally charged society that does not allow the freedom of thought. Rarely do individuals with opposing opinions discuss their points of view calmly and maturely," he explains.

Kareem, an Egyptian Muslim, who considers himself secular, says he avoids talking about religion because of sensitivities.

"Muslims are the overwhelming majority here, I don't need to discuss Islam in front of my Coptic friends who are already on edge [due to religious/political tensions]."

Dina, a Syrian-Palestinian Muslim, says not only do Arabs rarely discuss other religions, but they shy away from introspecting on their faith.

"We are only challenged by the West. We take any criticism from them to be politically motivated so we automatically reject it. We are a closed society and we lack introspection," she said.

Do you think that religious conversion is a taboo in the Middle East? Do you openly discuss religion among your social circles or do you try to avoid it? Have you or anyone you know converted?

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox