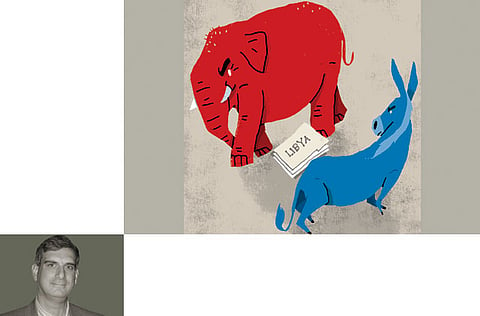

Little to choose between camps

Libya debate raises more questions than answers about the Republicans

The emergence of Libya as a significant issue in the US presidential race has been a surprise. It is not going to decide this election, but it is not inconsequential either and how it is being handled raises questions about both sides.

For President Barack Obama, these questions are relatively straightforward and focus on the administration’s response to last month’s attack on the US consulate in Benghazi.

This is not to discount the attack itself. Clearly the State Department and Congress need to look carefully at the incident. Figuring out exactly what happened and trying to prevent something similar from happening again is both necessary and important.

Of more immediate concern, however, is why an administration with a reputation for being good at foreign policy has handled the weeks since the attack so poorly. The White House and State Department have not always been on the same page. Administration spokespeople from Vice-President Joe Biden have changed their accounts of what happened in Benghazi multiple times and now routinely tie themselves into rhetorical knots whenever the topic comes up. In the process, they have given Mitt Romney’s presidential campaign an issue at exactly the moment when it needed one.

One of the basic rules of governmental crisis management is to think and act carefully as events unfold because initial reports are always fragmentary and usually wrong. That is why it was a mistake for Mitt Romney to issue a statement flaying Obama’s actions even as events in Cairo and Benghazi were still unfolding (at the time the trouble at the two diplomatic missions appeared to be linked, though that no longer seems to be the case).

It is also, however, why the Obama administration’s repeated changes of direction on the Benghazi attacks are made worse by its insistence that whatever version it is currently offering is definitive. Our understanding of an event like this is inevitably going to evolve over time as investigators, soldiers, diplomats and journalists reconstruct what happened and as new evidence comes to light.

Thus it beggars belief that someone in the White House chose to send UN Ambassador Susan Rice out to do a round of national television interviews in which she repeatedly declared that terrorism had nothing to do with the events in Benghazi. Based only on media reports from the scene that assertion was questionable when she made it. Today, it appears to be flatly wrong.

If we were not three weeks from a presidential election, the contrast between what Rice said last month and what we know today would be embarrassing for the administration, but hardly some sort of defining foreign policy moment.

With the campaign moving towards a crescendo, however, it has left Obama’s team looking inept at a moment when they can least afford it.

In a narrow sense, this is good news for Romney, if only because the administration’s repeated fumbles in the weeks since the Libya attack have diverted attention from Romney’s tone-deaf and deeply unstatesmanlike reaction to the initial violence.

For anyone really paying attention, however, Team Romney’s handling of the last two weeks actually raises more questions than it answers. Romney has sought to make Team Obama’s confused response to Benghazi the foundation of a broader indictment of Obama as a weak, essentially passive, foreign policy president.

The question the GOP {Grand Old Party, read Republicans] has so far failed to answer is what “president” Romney would actually have done differently. When the former Massachusetts governor gave what was billed as a major foreign policy speech last week, most of the foreign policy establishment noted that his criticisms of Obama often amounted to little more than a call for America to posture more belligerently on the world stage while doing pretty much what it does now.

That, in fact, may be Romney’s biggest problem when it comes to foreign policy. Right now, much of the wider world likes Obama’s style even as it voices disappointment with how little his substance differs from George W. Bush. Romney proposes not only to continue Obama’s Bush-like foreign policy, but to do so by bringing back both Bush’s key aides and his chest-thumping attitudes.

This is not a policy designed to win America many new friends in the Middle East, or anywhere else for that matter. The scary thing about both Romney and the people around him is that they appear to know this and do not really care.

Gordon Robison, a longtime Middle East journalist and US political analyst, teaches political science at the University of Vermont.