Decoding Delhi Durbar: How the British tried to rewrite India’s history

A story of Empire, display and the possession of history through years of Early Raj

Often history can be sensed, deconstructed through the material culture of the times, accrued over live events that happened back in time.

This exactly is the premise on which DAG, one of Asia’s finest art companie, has based its brilliant initiative — ‘Delhi Durbar — Empire, Display and the Possession of History’.

Curated with care and grandiose by two well-known historians Swapna Liddle and Rana Safvi, the project under the aegis of Ashish Anand DAG’s CEO and MD has resulted in an exhibition and a luxury collectible book on the same theme and name developed from the vast collection of DAG ranging from photographs, portraits, medals, maps, official guidebooks, tents, canopies, tickets, photographs, souvenirs and more, all connected to Imperial Assemblages that were held in Delhi during the years: 1877, 1903 and 1911.

In these times of decolonisation, it is interesting to know the significance of these materials, the narrative they help create, which in turn opens up to the most complex phase of forced take over in modern history of India. It is the historical perspective, base for these assemblages called Durbars and why they took place in Delhi.

Liddle notes in the book catalogue “The choice of Delhi was made with deliberation. Delhi’s central location and excellent connection by train to far flung regions of India were important criteria for choosing it but equally important was the desire to make associations with India’s imperial past”.

Ironically the British colonisers wanted to erase India’s imperial past — read Mughals — from public imagination. To that they had left no stones unturned as they suppressed the Uprising of 1857, defacing Delhi, killing thousands and yet in their own interest they needed Delhi to return to limelight.

An Imperial Assemblage thus would mean resurrecting Delhi, its architectural facades, putting new life to its artistic traditions, crafts and culturally unique ingredients, in sum dealing the ghosts of the Mughals.

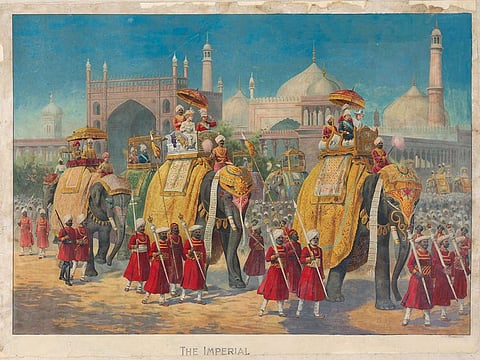

In the same edition Safvi nails it, “The word durbar itself was borrowed from the Mughals, as were the symbols of sovereignty such as elephant processions, elaborate ceremonies and distinctly oriental design for the Coronation Durbar. In that sense there was a sense continuity with the previous rulers, but along with it was a sense of appropriation and imposition of British rule over India. “

Dealing With the Ghost and The Resultant

Imagine a January day of 1858’s Delhi a rolling murmur blankets the 18 x 10 yard all marble rectangular pavilion of Diwan — e — Khas in Red Fort designed with twelve ornate columns, arches that have intricate ornamentation of floral motifs, free flowing vines.

Here in this hall stood Shah Jahan’s peacock throne before the Persian ruler Nadir Shah ravaged Delhi in 1739 stealing one of the most bejewelled objects in the world along with a plethora of loot. That day in January in the same palace pavilion began the trial of Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar, addressed as King of Delhi.

A witness to many high and lows, the seat of Mughal rule stood silent as the special court pursued the trial leading to the exile of the emperor and his family to Burma, now Myanmar.

This is well known! But perhaps this was also the day when British colonial administration decided to imbue their ownership over the vast empire of India once for all. One wonders if the image of the convicted Emperor spawned the idea of refashioning kingship which would be a reality manifested in next two decades through the three larger than life Durbars officiating empire.

In other words it was a political, cultural exercise in understanding in Indian minds, “To begin with the British wanted to replace the Mughals in the loyalty of the Indian people. We thus see that the first proclamation in 1877 was not called a durbar, but ‘Imperial Assemblage’, and even the style of the decorations etc, was British rather than Indian.

Soon however they realised that in the minds of most Indians, royalty and sovereignty was associated with certain rituals and symbols that were a legacy largely of Mughal rule.

The British therefore decided that in order to appeal to Indians, they had to repackage British rule as the ‘Raj’ — a successor to the other Indian empires, particularly the Mughals. This the two subsequent durbars tried to do in many ways, through some heavy symbolism of space and style” reflects Liddle in her curatorial note.

Interestingly the proclamation was “beyond bare announcement of the administrative changes and was a message of peace and conciliation in the context of the revolt” she further writes, noting it as ‘remarkable charter of promises.

In its literality, the remarkable charter needed to take up a spectacular form of an event that would go well with all Indian Princes and British officials. This would result in the gathering, the primary interest of which was to reaffirm the suzerainty of the British Crown on the Indian Princes and on the affluent, educated Indians.

Stephen Wheeler, the British chronicler of the event, readily addressed it as “one of the oldest institutions in India”. He also denoted the assemblage as “celebrated in this fashion as oriental climes” quickly comparing it with the likes of Chengiz and Timur, Cyrus and Ahasuerus.

While repackaging continued through the Durbars, the tangible achievements of the British included assumptions of royal title “Empress of India” by Queen Victoria and shifting of the capital from Calcutta to Delhi.

The razzmatazz of the first assemblage of 1877 saw sixty-three princes as attendees, many of whom were meeting for the first time. Iconic celebrations took place with Viceroy’s arrival followed by royal procession that went on for hours much like the Mughals. In fact the Viceroy rode an elephant that en route Jama Masjid, Chandni Chowk parts of Shahjahanabad evoking memories of Shahjahan era, when lavish gatherings were frequent.

Liddle notes, “The transfer of the capital to Delhi, which had been a historical capital of Indian empire for several centuries, was the logical conclusion to that aim and impulse”.

Therefore, Delhi needed to be carefully repurposed, and refashioned. Paradoxically this was the same city that they had destroyed brick by brick just twenty years ago. The organisers wanted similar opulence but still be distinct. To that Viceroy Lytton and his team came up with the term Kaiser -e- Hind as the imperial title which they thought was distinct enough.

The distinctness also came into play through unbelievable fanfare markers of ownership, restoring ‘Delhi’ as the historic centre of political legacy.

Meanwhile all the coronational events generated lot of excitement not only for its organisers and attendees but also for entities of media in England and India, many of whom were covering them for official records or for larger public consumption. However it also brought criticism like Lockwood Kipling’s production design of the dais was criticised as “over-ornamented”!

But that did not discourage the British to appropriate Mughal visual imageries, styling. Fascinatingly even the proclamation of Queen Victoria was “read out in English and Urdu on Jan. 1, 1877” mentions Safvi in her essay.

Curzon went great lengths to give the celebration a Mughal feel. To that extent even A House of Marvel was created. This was specially used to store the collectibles once ordered by the Mughal emperors, including expensive silk, brocade, carpets, jade, gold and silver artefacts, jewelleries and what not. Both Diwan -e-Aam and Diwan-e-Khas were customised according to the event.

“In fact the Palace Complex (present day Red Fort) was used for the Grand Ball during the Durbar of 1903, the coronation event of Edward VII”, writes Liddle. Her understanding is further expanded by Safvi, referring to Wheeler’s ‘History of Delhi Coronation Durbar’ where he highlights Curzon’s psyche, “Since Lord Curzon was very clear that the entire building had to be Mughal, it was very cleverly done and the additions added seamlessly so that dancers at the ball was unencumbered by any pillars.”

The Appropriation and The Present-Day Decoding

Needless to say, such display had a left a vast repository of ephemera that form discourse on cultural imagery and material history of pre-independent India.

Today the items are part of private and public collections — the prime being DAG archives which made their appearance for the first time in a public via the recent exhibition and book titled ‘Delhi Durbar’, Empire, Display and The Possession of History’.

Ashish Anand CEO and MD reveals the core thought behind mounting this fabulous show and also producing it as a book-catalogue, “the idea is to introduce this wealth of historical material archive to audiences through our exhibitions and books. I do not think we have had another exhibition in our galleries that has drawn the nature and quantities of visitors that Delhi Durbar has. It shows how people engage with history with much greater enthusiasm if they can do so through the medium of material culture”.

The erudite curators have their expressions too. Safvi feels, “we have tried to see the Delhi Durbars from a contemporary Indian lens”, Liddle affirms that, “the curation of this exhibition is a bridge between the historian’s craft and the intent to display the material in a given archive”.

Thanks to DAG and the curators, the study of material history as an essential is brought to fore. With rising public interests in ephemeral culture, one can only hope that India’s most nuanced past that eventually led to nationalist movement would be of interest to many and yes, the realisation that British colonial rule appropriated most things Mughal when it came to packaging themselves for Indians.

Mughals were no less than Banquo’s ghost in Macbeth who they had no way but to live with.

Nilosree is a noted author, filmmaker