For the last several months, the United States and North Korea have been stuck in a mutually reinforcing cycle of escalation. The possibility of the confrontation spiralling into a horrific, full-scale war — either by design or by accident — has become increasingly likely.

US President Donald Trump has portrayed North Korea as uninterested in finding a peaceful way out of this standoff. On Tuesday, during a visit to South Korea, the president took a different tone, declining to reaffirm his previous statements that negotiations are “a waste of time.” The approach he showed in Korea was certainly better than his past bluster, but they still fall far short of what is needed.

Over the last year, the two of us have been part of informal discussions with North Korean officials also attended by former American government officials, retired military officers and experts. While determined to pursue a nuclear arsenal to defend their country, the North Koreans say they are also open to discussing how to avoid a disastrous confrontation. Even before Trump took office, North Korean government representatives sent signals that they were open to dialogue. In a meeting in Geneva shortly after the American presidential election, they expressed a willingness to consider resuming contacts that had been cut off the previous summer.

The North Koreans also raised the possibility of discussions to determine the agenda for formal talks that could tackle American concerns about Pyongyang’s nuclear and missile programmes and North Korea’s concerns about “hostile American policy” — the term they frequently use to refer to what they perceive as the political, military and economic threats posed by the US.

For the North Koreans, who point to the fates of Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi and Iraq’s Saddam Hussain as cautionary tales, demonstrating that they can build a nuclear missile able to reach the continental US is the highest priority. This was confirmed in Moscow a few weeks ago, when Choe said that North Korea would continue to develop these weapons until it reached a “balance of power” with the US.

This dark cloud may have a silver lining.

In our talks, the North Koreans have maintained that they are not striving to be a nuclear state with a big arsenal, but rather to have enough weapons to defend themselves. Since early last summer, North Korean officials have publicly said that they have entered the last stage in the development of their nuclear force, implying that they have an endpoint in mind. A senior North Korean official privately told us: “If we feel we have enough, the primary emphasis will be on economic growth.”

This potential opening for dialogue needs to be explored. We believe the best way to proceed would be to first hold bilateral “talks about talks” without preconditions. The objective of these talks would be to clarify the policies of each country, discuss where there might be potential compromises and what each side considers non-negotiable, and prepare the groundwork to move on to negotiations.

Ideally, this would be done through under-the-radar meetings by diplomats, similar to the initial contacts between American and Iranian officials that took months and eventually led to the 2015 Iran nuclear deal. In the current atmosphere of crisis, Washington should accelerate this process by appointing a senior presidential envoy to work with the US State Department and with top-ranking North Koreans.

A nuclear-free Korean Peninsula should remain America’s main priority. The Trump administration wants this to happen immediately, while some experts argue this objective should be dropped since it will be impossible to achieve.

We don’t agree with either position. The US has to be realistic. Denuclearisation cannot happen overnight. It must be framed as a long-term objective of any diplomacy, an approach the North Koreans have hinted they would accept.

In view of the mounting confrontation and the lack of mutual trust, the US must pursue a step-by-step approach to reduce tensions and secure a path to formal negotiations.

An essential first step is an immediate moratorium on North Korea’s nuclear and missile testing, which aggravate tensions. In exchange, the US and South Korea could meet North Korean concerns by adjusting the scale of their joint military exercises or perhaps offer some relief from economic sanctions. Other steps — such as assurances by North Korea that it will not transfer nuclear, chemical or biological weapons technology overseas — could follow.

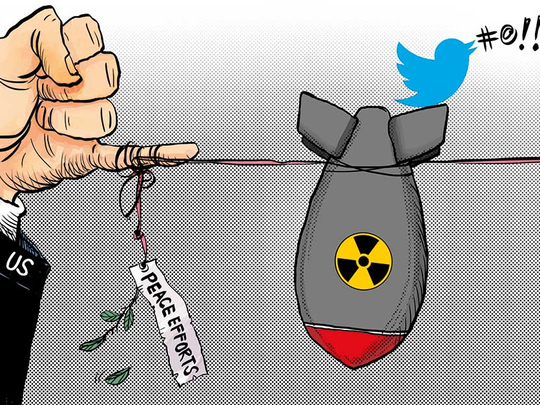

But none of this can be achieved without the right political atmosphere. The North Koreans are bewildered by the lack of coherence in American policy. President Trump’s threatening tweets and personal attacks on Kim Jong-un have only added to the risks of misinterpretation. Even his recent statements in Tokyo and Seoul, hinting at a willingness to talk, are at risk of being drowned out by his bluster, which reinforces the North Koreans’ mindset that they made the right decision by choosing a nuclear path.

Trump could begin reducing tensions by stating clearly that diplomatic engagement with Pyongyang is his administration’s first choice and that the US is ready to proceed down this road, working with its allies and partners. Such a statement offers the best way to sway the Chinese to better enforce sanctions against Pyongyang and would serve him well in his coming meeting with President Xi Jinping of China.

The US should understand that growing talk of military options will only strengthen Pyongyang’s resolve, not undermine it. Given the danger of a nuclear war, that would be a serious mistake.

— New York Times News Service

Suzanne DiMaggio is a fellow at the New America Foundation. Joel S. Wit is the director of 38 North, a Washington-based North Korea monitoring project.

_resources1_16a45059ca3_small.jpg)