How free meals fight classroom hunger in India

India’s mid-day meal scheme feeds nearly 100 million school children daily

On a wet July morning in Hasanpur village, children queue up at a shallow water well hand-pump. Teachers instruct them to wash their hands with a pink colour soap and guide them to a verandah at this primary school on the outskirts of the northern Indian city of Lucknow. It is lunch break at 10.30am and the school’s dining area is flooded with ankle-deep water following an overnight seasonal downpour.

Hasanpur primary school is special; the government designated it as an English-medium institution, a rare opportunity for village children to study all subjects in the English language. Located nearly 25km from the city centre, Hasanpur is a classic example of India’s widening gap between the poor and the rich. Next to the village is a brand new sprawling golf city township where the city’s rich pay tens of millions of rupees for row houses and apartments. Once ready, they will enjoy the lifestyle of a world-class gated community with a lush green golf course, shopping promenades, international schools and a quick 20-minute drive to the international airport.

At this school — the district’s oldest — however, little has changed in the last 40 years. It has a concrete structure with four classrooms, a small verandah, two dysfunctional toilets and a muddy courtyard. “We resumed classes this week after the summer break and spent money from our [own] pocket to get it cleaned,” Mrs Rajan, a teacher told Weekend Review.

At Akshaya Patra Foundation’s facility in the industrial complex of Amausi in Lucknow, strict hygiene standards are maintained

“We were horrified to discover that some people had defecated in the dining area… we got it cleaned, but now it is flooded,” she said, underlining the challenges of running a village school.

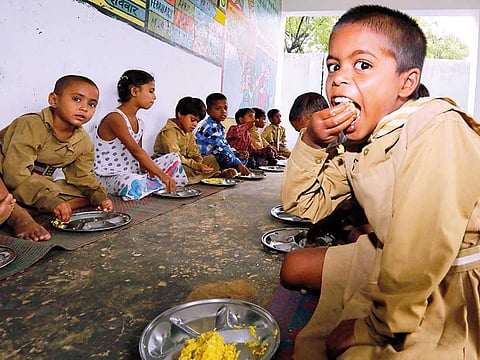

The students sing a prayer written by E. Rutter Leatham ahead of lunch, the day’s first meal for many in this village of a few hundred houses. An assistant brings two airtight steel containers to the verandah where children are sitting on the floor. Today’s meal is special — a generous serving of hot vegetable rice and milk pudding for dessert. The food is served to students in batches as plates are limited. However, no one is complaining.

Welcome to the world’s largest food programme where tens of millions of children are provided hot meals for 200 days in a year. Popularly known as mid-day meal scheme, it was launched in 1995 as a ‘National Programme of Nutritional Support to Primary Education’ to address “classroom hunger”, and aims to boost school enrolment, retention and attendance and also to fight malnutrition among children.

Hasanpur primary school is one of more than 1.2 million government-funded schools in India where about 100 million students get one free meal a day under the state-funded programme. Here, the meals come from a kitchen located 20km away at Amausi industrial park. The large kitchen is run by Akshaya Patra Foundation, a nongovernment organisation that prepares 1.6 million meals daily at 26 facilities in 11 states in the country.

Impact and challenges

The programme was first conceived by the British in 1925 in Madras, now Chennai, the capital city of southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, before it was launched in Calcutta (now Kolkata) in 1928 and later by the French administrators of Pondicherry (now Puducherry) in 1930. The federal government formally adopted the programme in 1995 to target “every child in every government and government aided primary school”, according to a study published in International Journal of Applied Research last year. The objective was to provide a 300-calorie meal with up to 12gm of protein content for 200 days in a school calendar year.

So, what has this programme done to improve school attendance and fight malnutrition among children? The answer to this question is complex, given the large footprint of the programme and enormous challenges of delivery of welfare projects.

Meals are being loaded on to vans for delivery to schools

In an interview with Weekend Review, Madhu Pandit Dasa, chairman of Akshaya Patra Foundation, said: “The impact has been positive with a significant increase in enrolment and attendance rates in these schools and decrease in dropout rates.

“For children, mid-day meals serve as an incentive to come to school. Parents are now willing to send their children to school instead of sending them to work to support the family, as that guarantees them one proper meal. The trend of parents discontinuing their children’s schooling to send them to work once they reached a specific age has also been reversed, thus resulting in a decrease in dropout rate,” he said.

Citing a study conducted by Kusuma Trust in Odisha and Andhra Pradesh states, he said parents changed their child’s school as they wanted to send them to a school where they would get free mid-day meals. Another study in 2014, Dasa said, found that attendance was above 90 per cent in eight states.

Another area where the programme has paid dividends, according to Dasa, is increased enrolment of girls. “Earlier, people would pool resources to send sons to school… Daughters were expected to learn household chores at a young age. Things have changed since; now people are willing to send their daughters to school.”

School children at Hasanpur primary school line up to wash their hands with soap and water before having their mid-day meal

However, other independent studies are sceptical of these claims. A study published by International Journal of Applied Research said mid-day meal is not the only factor that attracts children to school. There are many other factors responsible for enrolment and dropout of children. It aims to address classroom hunger and is successfully doing that. But there are many shortcomings: many schools have no plates and children are forced to use “pattals” (plates made from dry leaves); though children are learning good habits such as washing hands before and after eating but the food itself is not hygienic and the cooks do not follow hygiene guidelines, the study found.

Poor infrastructure

Doubts raised by this study are not without any basis. NGOs like the Akshaya Patra Foundation provide only two per cent of the 100 million state-funded meals. The remaining are prepared by headmasters, teachers and staff in remote schools which lack even the most basic infrastructure, including water, toilets, concrete structures and kitchen. A majority of these schools face the risk of food poisoning and related health hazards due to lack of infrastructure and proper monitoring of the scheme, said a recent public interest petition seeking Indian Supreme Court’s intervention. In recent years, the programme has been tarnished by horrendous accidents claiming lives of scores of children in several states. In 2013, for example, 23 children died after consuming a meal of rice and soya chunks laced with a highly toxic pesticide in Bihar state. The school principal was sentenced to 17 years in jail after she was found guilty of culpable homicide and criminal negligence. While official statistics for the entire country are not available, media reports say hundreds of children have died in recent years in other states.

Delivery of welfare projects in a vast nation like India is a humongous task and not without massive pilferage and corruption. Just last year, India’s audit watchdog flagged shocking instances of bureaucratic red tape and corruption. “Despite release of funds by the government of India for kitchen-cum-stores, the state governments and implementing agencies failed to release these funds on time. This resulted in improper storage of food and cooking of meals in classrooms or open spaces in 14 states,” the Comptroller and Auditor General or CAG said.

Citing specific instances, the watchdog lamented poor implementation of the programme. “In Orissa, during test check, it was observed that 92 per cent of the schools did not have kitchen sheds. In Uttar Pradesh, many test-checked schools did not have sufficient utensils. In primary schools at Lohari, Jhansi district, empty paint containers were used for serving meals,” it said.

Supporters of the programme, however, argue that the watchdog’s report should be used to improve delivery. “What the CAG has done is an ‘audit’ of the scheme using the same method as in a financial audit. While this exercise has merits, it cannot be treated as an overall assessment of the scheme. A number of studies of midday meals in India have shown that the scheme not only enhances school enrolment, retention and attendance but also has positive effects on child nutrition. Nothing in the CAG report invalidates these findings,” wrote Dipa Sinha of School of Liberal Studies, in web portal The Wire.

Akshaya Patra Foundation is also aware of these challenges in implementing a programme of this scale. “We wanted to reach out to children in remote areas of Baran (Rajasthan) or Nayagarh (Odisha), but it was difficult for us to set up centralised units in these areas because of the geographic terrain and remoteness. The answer came in the form of a decentralised model, wherein we hired women self-help groups to cook mid-day meals. Manually preparing rotis was another challenge we faced in the kitchens in north India, where roti is the main item, so we opted for a customised machine which helps us prepare 45,000 rotis in an hour,” says Dasa.

Despite the challenges, Dasa believes the programme is also helping improve nutritional status of children by providing them a wholesome meal every school day. “Our meals are prepared keeping in mind the dietary norms stated in mid-day meal guidelines. This is all the more important as this is the only proper meal some of these children have in a day. It helps in shielding children from problems such as malnutrition, low energy levels, low immunity, etc,” he said. Malnutrition is widespread in India with a stunting rate of up to 38 per cent in some part of the country, accounting for a third of the world’s stunted children.

Back in Hasanpur, the school teacher Mrs Rajan also believes the programme is making an impact. “We have a strength of 132 children, mostly from the village and some children are from the nearby golf city where migrant labourers are living at the construction site. In the last two years, we have noticed some changes, the students’ academic performance has improved. Earlier, the food was cooked at the school and when the foundation started providing meals our headache has reduced and children get a variety of meals. The mid-day meal programme has definitely improved attendance but the teaching staff also has played a role in improving enrolment and retention,” she said.