A classical understanding

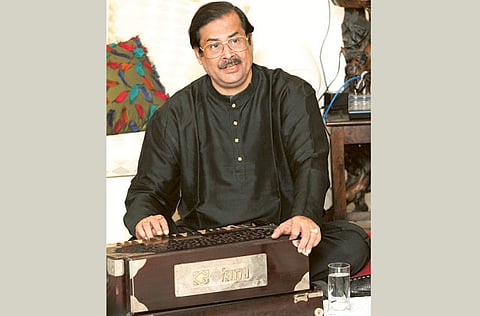

Pandit Ajoy Chakraborty talks about how the pursuit of music can give people a peek into their own souls

He was the first Indian classical singer to be invited by the Pakistani government to perform in the country; the first Indian classical vocalist to receive the President’s award for the best male playback singer; and the first recipient of the prestigious Kumar Gandharva Award and a gold medal from India’s premier music research institution, the Sangeet Research Academy. To cap it all, the Indian government honoured his musical genius with a Padmasree last year.

But ask Pandit Ajoy Chakraborty about what music means to him, and he says: “Music for me is not a subject to learn, to buy or to sell — it’s the oxygen I need to survive. I started learning music like any other student, but gradually found that music is the only way for me to live.”

He speaks to “Weekend Review” after a gruelling (and free) tutorial session for more than 30 students between the ages of 5 and 50 at an improvised “classroom” in Dubai, which he is visiting for a sold-out concert. The tutorial was scheduled for an hour, but as with any concert or interaction Pandit Chakraborty is involved in, it ends after nearly three hours, interspersed with animated discussions whose topics range from tips on finding the perfect pitch to diets for controlling acidity to breathing techniques for increasing voice stamina.

An occasional glide of a raga (the melodic foundation of Indian classical music) escapes his richly textured voice and drowns out the surrounding cacophony; he is demonstrating the subtle nuances of tone and delivery, which he feels separate a maestro from a musician.

Indeed, apart from being one of the greatest exponents of Indian classical music from the Patiala gharana (school), Pandit Chakraborty is also a rare embodiment of a maestro as much at ease with tradition as with improvisation — from an evocative rendering of a raga, to Sanskrit chants, to lending his voice for a playback song in a Bollywood film, to Bengali songs and collaborations on experimental music, Pandit Chakraborty can do it all.

He was born in 1953 in Kolkata, West Bengal, into a family that, like millions of others, moved from Bangladesh to India during the partition of the subcontinent in 1947.

So how did he get into music at such a time of political and social turmoil?

“When you are a child, most things are decided by your parents, and that was the case for me,” Pandit Chakraborty says. “My parents, especially my father Ajit Chakraborty, were excellent singers. But when they migrated from Bangladesh, their financial situation was quite difficult; they could hardly sustain their interest in music.”

“They saw the promise of their unfulfilled dream in me — I hardly had a choice,” he continues. “Times were difficult: My father often slept on pavements, and sometimes we wouldn’t even have enough food for all of us. But our collective quest in music continued, and I was very lucky to have connected with some of the greatest music maestros of our time. Somehow things worked out for me.”

That last bit is something of an understatement, I point out, considering that his own guru Pandit Gyan Prakash Ghosh — one of the most celebrated classical musicians of all time — said that during his lifetime he had not found any other student as accomplished as Chakraborty. He also received effusive praise under the tutelage of Ustad Munawar Ali Khan, son of the legendary Patiala-Kasur gharana maestro Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan.

“A guru is someone who’s not just a technical teacher, but he who also teaches you the philosophy behind the music you are creating,” he says, as he talks about his own gurus.

That said, he maintains, ultimate learning comes from within. “If you can’t follow your master’s philosophy and imbibe them, it’s useless to try to learn at all,” he says.

The fiercely competitive Indian music scene — whether classical or pop or fusion — is bursting with emerging talent backed by dozens of music companies and TV contests, I point out. Are they all imbibing music with such rigour and earnestness?

“When I started singing, I saw a very bright future for Indian music. But somewhere down the line, music has become one of the easiest careers to pursue, even for those who have absolutely no idea about the basics of music, the ragas, and can’t even sing sa-re-ga-ma properly,” says Pandit Chakraborty, referring to the seven fundamental notes of Hindustani classical music, which can be compared to Western music’s Do Re Mi Fa.

“These people, who call themselves musicians, make noise rather than music,” he says. “But this is actually our failure — we couldn’t convince and attract them with our musical heritage.”

The compartmentalisation of music into stereotyped genres such as classical and pop has also destroyed the core of music, Chakraborty says. “Classical musicians would not associate with, say, the music of Lata Mangeshkar or Asha Bhonsle. And the latter, in turn, would not normally associate with classical music, although they are geniuses and every Indian should be proud of them. There was no nurturing of talent across genres, which led to a situation where performers felt that these were mutually exclusive.”

Not someone to be content merely with analysing a problem, Pandit Chakraborty came up with a solution of his own — Shrutinandan, which means “pleasant harmony”.

That is the name of the music institution Chakraborty and his wife founded to bridge the gap between what he calls brain and heart, with a methodology of learning based on techniques that combine heritage and technology. He calls himself the first student of Shrutinandan, which is based in Kolkata. “Our ustads and pandits tell their disciples to never try to be a teacher, to always remain a student. The day you think you have become an ustad, your ability to create music is over. So I am merely a student of this great concept called Shrutinandan,” he says.

True to its concept of synthesising tradition and changing times, this school has embraced social media with the same vigour with which it imparts music. It has also extended its reach beyond the subcontinent through its online programmes, offering aspiring expats worldwide the opportunity to learn from one of the greatest classical musicians of India.

With hundreds of youngsters enrolled — some of whom are accompanying Pandit Chakraborty on his Dubai tour — the school is an obvious success.

But in an age where the average piece of music lasts four to five minutes and where remixes are often more popular than the original versions, what is the future of classical music?

“Classical music is like the great epics — they will endure while waves of new music will come and go,” the music maestro says. “And to create anything of enduring value, there can be no shortcuts. I see a lot of gifted aspiring singers on the scene now, but they can’t survive without hard work. Today, becoming a successful and famous musician is far easier than before, but to sustain that success and live up to expectations is the real challenge. For that, you need not only mastery over technique but also integrity and aesthetics.”

Which brings us back to where we started: What is music?

“Music is not an extracurricular activity. Music is the only way in which you can see your soul. No other education in the world can do that,” he says.

So what about the academic system and formal education?

“What exactly do we learn from formal education?” Chakraborty counters. “Two of the most talented people of our times, Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, didn’t even pass out from school. And in India, [Rabindranath] Tagore would be considered uneducated and illiterate by conventional education standards. So education is a way of life rather than an assortment of subjects and techniques to be learnt by heart, just as music is.”

Essentially, he says, music should be as integral a part of anyone’s life as the air they breathe, and that by mastering music, people can master anything they want.

“This is something I have seen from experience and learnt from personal involvement. You practise music for three to four hours every day, and your mind is ready to take on the most challenging academic or professional assignment. It improves your mental faculties and your thinking abilities. Most of my disciples have chosen to pursue music in life, but their academic records are impeccable and most are top-graders at colleges and universities,” he says.

Examples can be found in the Chakraborty family itself: His daughter Kaushiki, who graduated with first-degree marks in Philosophy, is, at 31, already an award-winning classical vocalist busy performing across India, Europe, the United States and the Middle East. His wife Chandana also has a first degree in music; so does Pandit Chakraborty himself.

He says he is particularly indebted to his wife for supporting the cause of music. “I have always given all my resources to music and Shrutinandan ... Without Chandana’s understanding, it would have been impossible for me to sustain my music. She is a qualified musician herself and has no demands other than music — she has never asked me for any expensive jewellery or any kind of material comfort. She was also my daughter’s first guru,” Pandit Chakraborty says.

And what about the prospects of Indian classical music in Dubai?

“Dubai is one of my favourite cities. I first performed here in 1996, and since then the cultural scene here has evolved a lot,” he says.

“It’s also one the cleanest cities I have seen,” he adds.

The maestro is impressed with the efforts of Dubai-based organisers Creative 9, who invited him, along with his family and his young entourage, for the latest concert, which promotes classical and semi-classical talents in the city. “We need more such efforts to bring not only established musicians but also young and emerging talent to inspire the people of Dubai. And my message to all such young musicians is: Be critical of yourself first, be very critical, and you will succeed in whatever you do.”

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox