Soon humans will be able to live 1,000 years

The single worst thing we do to ourselves that causes us to get sick when we get old is breathe, says biogerontologist Aubrey de Grey, who believes humans can soon live for 1,000 years

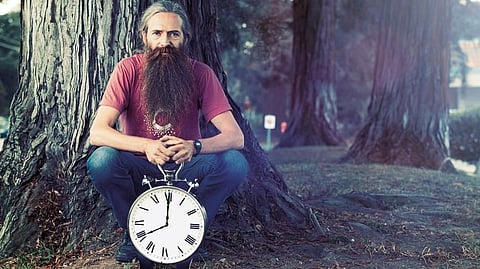

Head resting upon shoulder, his long, greying hair bunched into a ponytail, the nearly navel-length salt and pepper beard brushing the armrest of the chair, Aubrey de Grey, one of the world’s leading bio gerontologists, is catching twenty winks during a break between sessions of the Abu Dhabi Ideas Weekend at NYU last month.

Although it’s long past our scheduled interview time, I prefer not to disturb him and luckily, I don’t have to wait long. A couple of minutes later, the six-foot-tall scientist slings a backpack on his shoulder and grabbing a large glass of pineapple juice saunters to our interview room.

‘I was in Prague yesterday and just flew into Abu Dhabi today,’ says Aubrey, as we sit down for a tete-a-tete. The brief shut-eye perhaps helped; despite the six-hour flight, the 55-year-old researcher is excited to talk about his life-altering research project that is gathering pace.

The chief science officer at the California-based Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescene (Sens) Research Foundation, a regenerative medicine research centre, and his team of scientists are working on a project that could make age-related diseases a thing of the past. In a nutshell, their mission is to extend the healthy human lifespan to a 1,000 years. In fact, Aubrey made a breath-taking announcement three years ago that the first person who will live to be 1,000 years has already been born.

Is it feasible, or even imaginable, to live to a 1,000 years? I ask Aubrey. ‘I think it’s very dangerous when we are thinking about technological aspects of the future to be distracted by what’s imaginable,’ says the British author and path-breaking scientist in human longevity research.

‘For instance, the prediction of trends in future purchasing habits of society is completely unsuccessful if you ask people what they want, because they can only imagine a limited amount, and then other things come along that they had not thought they wanted. ‘The only way we can really ask the question ‘Can people live far longer than they’ve ever lived before?’ is to ask ‘What would it take technologically to piece it together from the bottom up?’ Then, yes, it’s perfectly imaginable.’ And Aubrey’s team is planning to piece it together by focussing on repairing the microscopic damage that occurs to cells over time that accompanies ageing and ageing-related diseases.

According to the fellow of the Gerontological Society of America, there are seven biological factors responsible for cellular damage, including cells that don’t die when they should, cells that replicate uncontrollably, cells that don’t get renewed quickly enough and cells whose DNA gets damaged for various reasons. ‘The utility of this classification – and this is often misunderstood – is that within each category there is a generic approach to doing something about it: to repairing the damage.’

But aren’t anti-ageing treatments quite like a Whack-a-mole game? I ask him.

Aubrey takes a large swig from the glass of pineapple juice he is clasping with both hands. ‘If we treat the problem of ageing as a collection of diseases then it is, indeed, a Whack-a-mole game. There are so many things that go wrong with life and they go wrong more or less at the same time. So it’s really hard,’ he agrees. ‘It’s here that the field of gerontology becomes relevant.’

While treating ageing is not easy, one possibility is to approach it from the point of preventative maintenance, he says. To that end, researchers examined the fundamentals in people’s lives that got them into the stage of ageing in the first place. In particular, experts tried to understand why there is so much variation in the natural world vis-a-vis longevity.

Quahog clams, for instance, live exceptionally long lives. One clam picked from the depths of the Atlantic Ocean was found to be a jaw-dropping 500+ years old. (In case you are wondering, growth rings on the shells offer scientists clues about molluscs’ age.) At the other end of the scale, the female mayfly goes through her entire lifecycle – emerging from an egg, finding a mate, consummating the relationship, laying eggs and dying – in less than five minutes.

‘It was nice to find out what makes some animals different from others and some individuals within a species,’ says Aubrey. ‘Unfortunately, that also has a problem of complexities in that the underlying things that make some animals live longer are very, very intricate and hard to understand. So, we needed a third way of going about this.

The third way he came up with – that appeared much more promising ‘and to avoid this Whack-a-mole problem’ – is to go halfway between the other two ideas of preventative maintenance and curing a health condition. ‘It was to attack the various types of molecular and cellular damage that accumulate in our body throughout our life … attack them before they get to a point where they are bad for us,’ says the fellow of the American Ageing Association.

So, is prevention better than cure? I ask.

Aubrey takes a sip from his glass of juice.

‘The word ‘cure’ is a bit dangerous,’ says Aubrey, also the international adjunct professor of the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology. ‘It’s a word that’s in use to describe what we do in case of infections… eliminate infections from the body. And the kind of mistake, the whack-a-mole mistake with relation to geriatric medicine is exactly that – it’s trying to eliminate ailments and cancers from the body.

‘These things cannot be eliminated, simply because these are side-effects of being alive. So we have to treat them in a different way… stop them from happening. It’s doing pre-emptive preventative maintenance.’

The maintenance Aubrey is referring to is, in essence, a set of rejuvenation biotechnologies based on the principles of regenerative medicine that not only slows down the accumulation of ageing damage in our tissues, but removes, repairs or replaces the damaged cellular and molecular machinery.

With every round of therapy, the person’s organs, nerves and bones will become more youthful and healthier as the cells will be repaired progressively restoring them to their youthful integrity.

While that appears potentially life-changing, I ask Aubrey if Man was ever meant to live a 1,000 years.

‘Who gives a damn?’ he says. Then leaning forward and looking me in the eye, he adds: ‘I’m not a philosopher. I’m a practical guy. As far as I’m concerned, humanity has evolved as a species that has the will and the ability to manipulate nature for its own ends. We have technology; and technology has been doing just that – whether it’s fire, the wheel or whatever. Medicine is simply a branch of technology. Was medicine meant to exist?’ He pauses to take another sip from his glass of juice after making the rhetorical question.

Aubrey did not start his career in biology or medicine. After graduating in computer science from Cambridge, the Briton, by his own admission, became ‘a very good programmer.

‘I thought I could solve the really important problem of tedium – the fact that people are spending so much of their lives doing stuff that they would not do unless they were being paid to do – by automation. So I thought I’ll work on artificial intelligence.’

He was enjoying a successful career in IT until his now ex-wife Adelaide Carpenter, a senior professor in biology, piqued his interest in biology and medicine. ‘I learnt a lot of biology through her,’ he reveals, ‘but while we used to discuss many subjects, I slowly realised that we were never talking about ageing.’

Ever curious to learn new things and solve scientific conundrums, Aubrey kept wondering why his wife, 19 years older to him and a respected geneticist in her own right, rarely if ever discussed ageing.

‘I used to keep telling her “It [ageing] is bad for you; it kills people,’’ and she would say, “That’s kind of not my problem’’,’ he says.

Aubrey, however, refused to give up. Determined to tackle ageing, he decided to switch from IT to biology ‘because this was a much more important subject’.

Returning to his alma mater – Cambridge – he earned a PhD in biology in 2000, and began work on a plan aimed at preventing age-related physical and cognitive decline before co-founding the Sens Research Foundation in 2009. Setting aside $13 million of his $16.5 million inheritance he received upon the death of his mother Cordelia, an artist, for his project, he encouraged a team of scientists to find ‘effective life extension interventions.

‘Since the dawn of civilisation, we’ve known that ageing is a ghastly thing. It kills everybody and yet there’s nothing that we can do about it. So we have had no choice [but] to find crazy ways to put it out of our minds and get on with our miserably short lives and make the best of it. And we are still doing that,’ he says.

What have been the biggest stumbling blocks on his road to research?

‘[Lack of] money, money and more money,’ says the editor-in-chief of the academic journal Rejuvenation Research. ‘That’s the truth.

‘When I started out, I had to figure out only three things: how to defeat ageing; and I managed that in one eureka moment in 2000 when I found out that comprehensive preventative maintenance was the way to go.

‘The second problem was to persuade leading scientists that this was something they ought to be working on. That turned out to be easy; scientists like to do interesting stuff.

‘Third, I had to find the money to pay these people. I’m continuing to do that now; it’s becoming progressively easier but it’s still hell on wheels to get funds in the door.’

Do increasing pollution levels and our junk food indulgences, among other things, exacerbate molecular and cellular damage? I ask the expert on ageing.

‘These things do have an effect,’ he agrees. ‘But we mustn’t get it out of proportion. It remains unequivocally the case that the main things that cause us to get sick when we get old are intrinsic to the way the body works.’

Aubrey then makes a startling statement: ‘The single worst thing we do to ourselves that causes us to get sick when we get old is – breathe. Breathing is incredibly bad for you.’

He takes another sip of his pineapple juice while I ponder if I should hold my breath for a while and thereby extend my life by at least a few minutes. ‘Breathing is the source of free radicals. It damages the DNA and so on; it’s a bit non-negotiable really.’

Since suspending breathing isn’t really an option as a plan to extend our lifespan, what other tips can he suggest that we should be doing right now to prolong our health and thereby our longevity?

‘Oh, the same family stuff you’ve been told about since you were perhaps two,’ says the scientist.

‘Don’t get overweight; have a reasonably balanced diet; don’t smoke… You don’t really need me to tell you that. Then there’s the need to make the research happen faster. The faster we get this done, the more lives we’ll be able to [extend].’

Is he irked by the scepticism that he has to face from longevity nay-sayers?

‘For a very long time, there’ve been people trying to convince the world that they could cure ageing; and they have all been wrong. So, it’s reasonable to have a certain degree of healthy scepticism when somebody else comes along and says they can do it. But, eventually, someone’s going to be right,’ he says.

How close is he to getting it right?

Aubrey takes another sip from his glass and leans back in his chair. ‘I often wonder how optimistic or pessimistic I should be on this,’ he says, his blue-grey eyes twinkling. ‘And I think I’m probably becoming more optimistic.

‘The concept of a preventative maintenance approach against ageing is, by definition, a divide and conquer approach where you have different kinds of damage and each has to be approached by different types of therapy. Some of them are further along than others,’ he reveals. Parts of the process, like stem cell therapy, are already in clinical trials. Other areas that Sens has pioneered are within a year or two of clinical trials.

‘People always think I am ridiculously optimistic but I think I’ve actually been slightly cautious over the years. I think we have a 50-50 chance of getting to what I call ‘‘longevity escape velocity’’ … where we are postponing ageing faster than time is passing by more than one year per year.

‘We are likely to get there within the next 20 years. It does again depend on money but that is also improving.’