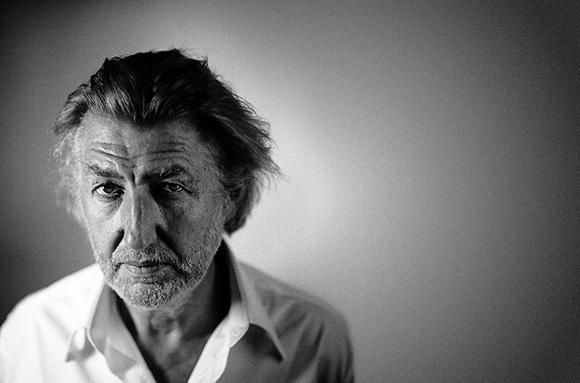

One of the first things you notice about Pierre Gagnaire – the man recently voted the planet’s greatest chef – is that he doesn’t really look like someone who works in a kitchen. He looks more like an artist and maybe a libertine.

He’s 65, has a whiskery white beard, rakish floppy hair and piercing blue eyes. He wears his shirt unbuttoned half way down his chest and his shoes without socks. When he speaks – during an interview at his InterContinental Dubai Festival City restaurant Reflets – it’s with an accent so French you half wonder if he’s putting it on. When he smiles it’s with a twinkle that’s just vaguely dishevelled.

The other thing you notice about Pierre Gagnaire is he doesn’t talk too much about food. Not directly at least. He speaks in similes and metaphors. Eating, he says at one point, ‘is like a love story. You fall in, you fall out’.

His reference points are poets, painters, jazz musicians. When I ask him what it felt like to win a recent ballot of 300 Michelin-starred chefs – polled by the French magazine Le Chef – to be named the world’s greatest, he shrugs. ‘Van Gogh, Rubens, Cézanne, Pollock,’ he says. ‘Who is your favourite? For you, it is different to me. It’s impossible to say who is number one. If I was a teenager I would be “yeahhh” But I’m not so young.’

His hero, he says, is the French-Algerian architect Rudy Ricciotti. His inspiration is the late American free-scribble artist Cy Twombly.

‘My goal is to make food like these paintings,’ he says. ‘It’s not well done like, say, Picasso. But it’s done by instinct. Twombly has perfect technique but he works from here instead.’ He points at his heart.

Then he takes a sip of his drink. He looks just a little like French poet, artist and actor Serge Gainsbourg.

In fact, the symbolism is all so overwhelming that, at one point, I ask if he sees himself as a tortured artist, only with produce as his palette. The question gets misunderstood. I don’t ask it well enough. There’s a blip in translation. He ends up thinking I’ve asked if he’s a little crazy.

‘Yes,’ he exclaims, loudly. ‘All chefs are. You must be to do this job. The stress, the heat, every night reaching for the top of the mountain. It’s too much otherwise. Yes, crazy.’

P ierre Gagnaire is, actually, not that crazy. His food may be the stuff of genius (he makes egg and olive-infused meringues that reviewers almost combust over). But the evidence shows he’s a canny businessman too.

He owns multiple restaurants across the globe, stretching from Seoul to Las Vegas.

How much this portfolio earns, he doesn’t say. But you can bet your last croissant, he won’t pass away artistically impoverished. Between them, his places have 13 Michelin stars. The one where he spends most of his time in the kitchen – called simply Pierre Gagnaire in Paris – has three. You can’t get any more. Between 2006 and 2008, for three years running, it was named the third finest eatery on the planet at the prestigious World’s 100 Best Restaurants awards.

Even now, when it’s slipped down to 92, Chef Gagnaire’s reputation remains sky high.

Still, I ask, why the fall from the top three? ‘Impossible to say,’ he says. ‘There’s no explanation. The list is about changing tastes. It’s no reflection on us.’

But did it hurt, I wonder. There’s a pause. He may be reflecting on his own earlier assessment that such rankings don’t matter.

‘Yes,’ he says after a moment. ‘It hurts. You want to be the best.’

We’re talking today during one of the grandfather of four’s annual five-day visits to Dubai. He spends six months of the year travelling from his home in Paris to his restaurants across the world.

While he’s here at the InterContinental, he’ll be spending his days meeting and greeting foodies and doing media duties (‘I’m not sure what I say is interesting but I answer your questions. But I always want to ask about you too. Who are you?’). But by night he’ll be in the kitchen of Reflets, working on the menu, looking to improve the foie gras, the cabillaud caviar, the rib-eye beef.

After almost half a century in the industry, that’s still where he feels most at home.

‘In the kitchen you have no computer and no machines,’ he says. ‘You have new techniques but, at the end, all you really have is your personality and your energy and your produce, and the fire. It’s the same as it always was. And after, you share it with people. You have a connection with them. It’s fantastic.’

Later, I ask Reflets head chef, a 28-year-old Belgian called Francois Xavier Simon, what it’s like to work with such a legend in the profession. Is he scary? Is he strict?

‘He doesn’t need to be,’ Francois replies. ‘When someone like that tells you to do something, you just do it. You know it’s right.’

It was 1966 when Pierre Gagnaire first started working in a kitchen.

He was 16, and it was a summer job. His first responsibility was hauling 50kg of charcoal from the cellar to feed the oven. Yet much of his history remains of a mystery.

‘I don’t like to speak about it,’ he says. ‘It is the past. I’m 65, let’s speak of today and let’s speak of tomorrow. It is dull to talk of what’s gone. My past is all there on the internet.’

It’s not really, though. What we can piece together is that he went into kitchen work without enthusiasm, because it was the family business and he was the oldest son.

‘When I started,’ he notes, ‘it was my destiny, not my passion’.

After learning his trade in Lyon, he went back to take over the family restaurant in 1977; spent four years there; didn’t enjoy it; and struck out on his own in Paris in 1981.

It was while doing that, that he discovered his love of experimenting with ingredients. He didn’t just want to ‘cook a slice of beef and send it out’, he says. He wanted to experiment, to put a performance on a plate, to create dishes that wowed and wooed. ‘When I started, you had a recipe and you followed it,’ he explains. ‘No creativity. It was just a job. The key of my story was the moment I understood you could create something different with only product. You can give emotion. Put your personality on a plate. Like a concert or a piece of theatre or art. Food is the art of my life. It’s a way to create tenderness. The mission of a chef is to create the space for tenderness.’

It wasn’t easy. In the mid-Nineties, he went bankrupt. It’s possible his experimental food – dishes like tempura of Breton langoustine with cinnamon-infused beurre blanc – was simply too ahead of its time. This, after all, was an age when phrases like molecular gastronomy had barely been dreamed up.

‘Maybe,’ he says. ‘But I wouldn’t change my way to try to be popular. My view was that my food was more than food. I didn’t want to be conservative. I wanted to create something else. And I felt this was my destiny.’

Did he ever doubt himself, I ask. ‘Always, always,’ he exclaims. ‘But not at my base. I doubt all the time. But I have no doubts too.’

In 1996, he opened Pierre Gagnaire. This time there would be no failings. In 2002, he opened his second place, Sketch, in London. His empire has been expanding ever since. Now, he’s reached 15 establishments, I wonder if he’ll open anymore.

‘No,’ he says, definitively. ‘No, no, no, no, no. I don’t know. Maybe.’

Chefs, I’ve learned, have a habit of name dropping the famous faces they’ve fed. Who’s eaten at Pierre Gagnaire’s place we should know about, I ask?

There’s a look of disdain.

‘It’s not important,’ he says. ‘Yes, famous people. But this chef can say I served the Queen or I served him or her. That’s not the point. I respect that chef because when somebody does this, it is somebody who works hard and who is competent. But it doesn’t matter who they cook for. The only people who are important are the people you’re cooking for that night. You should treat everyone the same. If you come tonight, you are the king of this table.’

In similar contrary style, he won’t say what his last meal would be if he had the choice.

‘In this instance, it doesn’t matter what you eat,’ he says. ‘It’s about who you are with, about the humanity.’

And a final question as our hour draws to a close. Exactly why, I ask, does he think those other chefs voted him the world’s best?

Another shrug. ‘I just try to make my food the best quality it can be,’ he says. ‘I give everything I have. I can’t give less.’