‘Pather Panchali’, India’s most famous film, is 60

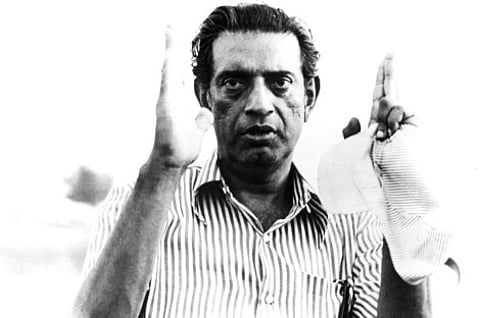

Oscar-winning director Satyajit Ray’s drama is often regarded as one of the best films ever made

No Indian movie has won more global recognition or praise than Pather Panchali, or Song of the Little Road, the debut film of the late legendary director Satyajit Ray, which celebrated 60 years last week amid tributes from around the world.

Pather Panchali was first released on August 26, 1955, in Kolkata’s Bashusree Theatre. Pather Panchali was the first Indian film to be noticed by the international art-house circuit, placing India on the world cinema map long before Bollywood acquired a global presence.

On its 50th anniversary in 2005, Time magazine placed Pather Panchali — India’s first art film and the harbinger of parallel cinema in the country — among the 100 best movies ever made. Along with its two sequels, Aparajito (1956) and Apur Sansar (1958), known as the Apu Trilogy, the triumvirate are 20th century classics and cultural milestones.

Pather Panchali proved to be the perfect launchpad for Ray: he made 36 films in his career; won laurels at the Cannes, Venice, Moscow and Berlin film festivals besides 32 Indian National Film Awards; and was given the Bharat Ratna, India’s highest civilian honour, a lifetime achievement Oscar and an honorary doctorate from Oxford University, making him only the second film personality after Charlie Chaplin to be accorded the privilege by the institution.

The 1955 masterpiece is a black-and-film with a running time of 126 minutes. But it packs quite a punch. Its realism is a treat for the eyes, heart and mind. Based on Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay’s 1929 novel, it captures the crushing poverty, joys and sorrows of a family of a couple, their son and daughter and an ageing aunt living in Nishchindpur village.

I had the good fortune of knowing Ray since 1982, when he was well established as one of the living greats of cinema, before I watched the iconic movie at a film society screening. Ray, in person, resembled a Greek god with the persona of a well-bred Oxbridge-educated Englishman. Frankly, he looked quite out of place in the chaotic city still called Calcutta in those days.

Pather Panchali left me speechless. I marvelled at the film for days after leaving the theatre. All the Bollywood films I had relished earlier suddenly seemed so contrived and downright silly. Besides striking images, the music scored by Ravi Shankar set it apart. I wasn’t surprised at all when I read much later that The Guardian ranked the film as the fourth greatest of all time.

When I met Ray next, I asked him the question many before me must have put to him: what drove him to make Pather Panchali?

Ray narrowed his piercing eyes and sized me up before recounting in his deep baritone how Italian neorealist Vittorio De Sica’s 1948 film Bicycle Thieves had cast a spell on him that intensified after Ray spent a weekend with French filmmaker Jean Renoir when he visited Calcutta in search of Anglo-Indian actresses for The River.

Peter Becker, president of Criterion Collection, the American video distribution company that restored the works of Ingmar Bergman, Chaplin and Akira Kurosawa before producing 4K digital prints of the Apu Trilogy ahead of Pather Panchali’s 60th anniversary, said: “Ray was the Indian representative of the Golden Age of Arthouse Cinema. He was legitimately the heir to [French director Jean] Renoir and [Italian director Roberto] Rossellini and a humanist filmmaker of the first order.

“The arrival of Pather Panchali represented an opening of the world to the cinematic audiences that has become accustomed to seeing Japan and Europe. Because he applied the principle of Italian neorealism, he built a global cinema bridge back and forth between Europe and India. Pather Panchali is a window into a past. It seemed remote even when it was made in 1955, when we didn’t have so many images from all around the world.”

John Powers, Vogue’s film critic, recently wrote that Pather Panchali expanded the world’s horizons by showing India as lived by and seen by Indians, not by outsiders with cameras.

“Ray went on to become one of the greatest names of international cinema, a director who wound up influencing everyone from French director Louis Malle and Italian director Federico Fellini to American filmmaker Wes Anderson and Hong Kong filmmaker Wong Kar Wai.

“Ray makes us feel the magic of feathery reeds in the sunlight, the terrible beauty of a monsoon deluge hitting dirty stone streets, the exultation of love and the inescapably of loss. Generous of spirit, his work possesses such warmth, tenderness and unforced naturalness that, by comparison, other movies, even good ones, can feel a bit like theme park rides or freakish sideshow attractions,” Powers wrote.

Interestingly, right from the beginning, there were dissenting voices that didn’t think much of Pather Panchali or its creator.

Before its commercial release in India on August 26, 1955, Pather Panchali premiered at New York’s Museum of Modern Art on May 3, 1955, for an invited audience. Although the film subsequently ran for eight weeks in New York, it left Bosley Crowther, film critic of The New York Times, cold. He wrote that Ray didn’t know how to make a film.

Similarly, Pather Panchali won the Best Human Document Award at Cannes in 1956 despite French filmmaker Francois Truffaut angrily walking out of the screening yelling that he had no time to waste watching natives eating with their hands.

Unbelievably, the film that became a touchstone of cinematic excellence was the handiwork of a bunch of first-timers. Ray had never directed a film before and his cinematographer, Subrata Mitra, had never shot a scene before with a movie camera. And the cast had not even been screen tested.

Ray had a tough time finding a young boy to play the central role of Apu. Ultimately, Ray’s wife, Bijoya, chanced upon Subir Banerjee who was prancing around on their neighbour’s roof. Ray instantly approved of the choice but the boy’s father feared that acting would hamper his education and destroy his future.

According to one account, the child actor’s father relented after Ray bluntly told him: “Today no one knows your son or me. But I will make a film which will change to face of Bengali cinema. Then, all of Bengal, will know both of us.”

But Banerjee, who was lauded as the world’s best child actor due to the phenomenal success of Pather Panchali, never landed another film role in his life. Now 70, Banerjee earned his living as a mill worker far. But two years ago, he became the subject of a fascinating documentary, Apur Sansar, which captured his life in oblivion after a brief brush with stardom.

How Pather Panchali was funded is equally incredible. Ray, who was a graphic artist in the art department of an ad agency, sold his books and long playing records to raise money for his dream project while his wife pawned her jewellery.

Ultimately, Ray sent an SOS through a family friend to Bidhan Chandra Roy, then the chief minister of West Bengal. Roy agreed in principle to bail him out but left it to his subordinates to find a way to help Ray. One bureaucrat mistook the incomplete film to be a documentary on rural upliftment. But another official with a long history of obliging politicians, capitalised on the film’s title and promptly allocated funds from the road department’s budget.

A grateful Ray organised a special screening for the chief minister soon after Pather Panchali was released to great critical acclaim abroad and in India. The then prime minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, happened to be in Calcutta on the day of the special screening and the chief minister brought Nehru along for the show.

Pather Panchali blew Nehru’s mind. He ordered officials to send it to the Cannes film festival. When a bureaucrat pointed out that the film would tarnish the newly independent nation’s image because it highlighted poverty and squalor, Nehru overruled him. The rest, as they say, is history.

Andrew Robinson, Ray’s biographer, once asked the maestro what he thought of Pather Panchali after all the adulation it had reaped for decades.

The reply was typical of the great man: modest and measured.

“It could do with some re-editing. It would improve. The pace sometimes falters; not in the second half, though. We shot the film in sequence, and we learned as we went along, and so the second half hangs together much better. But it would definitely improve with cutting.”

— S. N. M. Abdi, Indian journalist and commentator, writes across Gulf News

Here are some of the best compliments paid to Pather Panchali and its director Satyajit Ray:

Akira Kurosawa, Japan’s iconic filmmaker: Not to have seen the cinema of Satyajit Ray means existing in the world without seeing the sun or the moon.

Shoojit Sircar, Piku, Madras Cafe and Vicky Donor director: Pather Panchali is my Bible as a film director. I keep copying it consciously and unconsciously. I was left numb after watching it. It opened a new chapter in my life which is divided into pre-Pather Panchali and post-Pather Panchali phases. Now I’m in the latter phase.

Salman Rushdie, author: I am a great admirer of Pather Panchali and I place it above Citizen Kane as the best film ever made.

Arthur C. Clarke, science fiction writer: Pather Panchali is one of the most heartbreakingly beautiful films ever made. There are scenes I need never view again as they are burnt upon my memory.

Shyam Benegal, film director: Pather Panchali changed my life. When I first saw it in 1956, I was so struck by it that I watched it back to back a dozen times.

Martin Scorsese, Raging Bull and Taxi Driver director: I will remember the scene in Pather Panchali when young Durga and Apu run through the village meadows and notice a train whistling by in the distance.

Richard Attenborough, Gandhi director: I was absolutely bowled over when I first saw Pather Panchali. The whole trilogy to me is extraordinary.

Girish Kasaravalli, Ghatashvaddha and Dweepa director: We can call ourselves Pather Panchali’s children.

Amitav Ghosh, Hungry Tide author: I consider Pather Panchali as the greatest of Ray’s films. After watching it, I wrote a letter to Ray — The Japanese have a custom which allows people to pay homage to artists they admire by standing outside their homes, alone and in silence, until they’re invited in. You are the only person in the world for whom I would gladly do that.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox