Italy’s agent provocateur

A new biography of the controversial journalist Oriana Fallaci tries to rehabilitate her reputation

Oriana Fallaci: The Journalist, the Agitator, the Legend

Someone should write an opera about her: La Fallaci, beautiful, extravagant, courageous survivor of war and tempestuous love affairs, speaker of truth to power. But for now, Cristina De Stefano’s new biography of the Italian journalistic superstar Oriana Fallaci — unabashed hagiography to counter the writer’s late-life reputational demise — must suffice.

Fallaci was born in 1929 to working-class parents and proved her dauntlessness as a tiny, pigtailed bike messenger for anti-Fascists in the Second World War Florence, when she was just 14. By her early 20s, she was in Rome covering Hollywood on the Tiber, honing her craft on fizzy stories about European royals and Italian movie stars. Eventually she began travelling frequently to California, lounging poolside with more movie stars and filing more stories. She got herself assigned to cover Nasa and the astronauts she adored (one of whom, De Stefano speculates rather fancifully, fathered one of Fallaci’s pregnancies, which ended in a miscarriage).

Fallaci then moved on to the subjects that made her famous: war and global politics. Golda Meir, Henry Kissinger, Deng Xiaoping, Ariel Sharon and Ayatollah Khomeini were just a few of the world leaders and statesmen who submitted to her trademark hours-long interviews, enduring her provocative questions while sharing breaks with her ubiquitous cigarettes.

Her interviews remain studies in speaking truth to power. Interviewing Ayatollah Khomeini, she famously called the chador a “stupid, medieval rag” and took it off, provoking the Ayatollah to leave the room. (It is a testament to her journalistic power that he came back the next day.) She badgered Ariel Sharon about the meaning of the word “terrorist” and accused him of having been one himself. She got Henry Kissinger to compare himself to a cowboy, alone “with his horse and nothing else.” Nixon, De Stefano writes, “was not at all pleased by the cowboy metaphor.”

Despite — or perhaps because of — her fearsome reputation, during the zenith of her reporting career few world leaders turned her down. “I have instinct,” she said of her interview strategy. “I really listen to the people I interview. In a way, I’m kind of a witch.” But “many people criticised her style, finding it too provocative,” De Stefano concedes, and some accused her “without evidence” of making things up. “The essence of my answers in that interview was accurate,” Kissinger would say, damning her with faint praise.

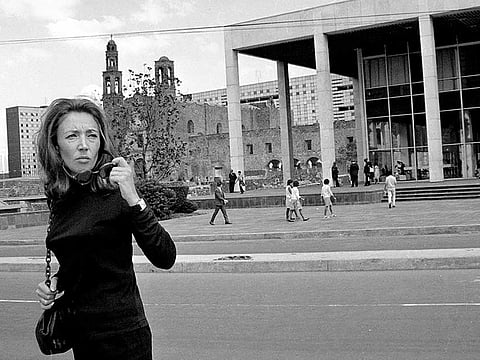

Fallaci was a piquant, stylish beauty, self-consciously photogenic in the Joan Didion way, a mid-century woman writer vigilant about her public image. Fallaci lived a genuinely romantic life, too, with stormy loves and war wounds. But De Stefano, who had access to living friends, family members and colleagues as well as archives and letters, reveals another side to her life — long periods of self-imposed emotional and actual isolation to devote herself to writing, interspersed with anguished affairs.

The relationships she forged with lovers — fellow journalists, a Greek revolutionary — were never lasting, and they often ended with her never speaking of them again, casting them into “the Siberia of my emotions,” as she put it. Her first love led to a suicide attempt and time in a psych ward, leaving her with the pithy conviction that “falling in love is giving oneself over to another, hands tied.” Later she would say, “Living together with a man, the man one loves the most, the best of men, is an intolerable torment for a modern woman.” Men, she continued, “seek a mother in every woman, and especially the woman they marry or live with.”

Her last romance was the most improbable of all, with an Italian soldier almost three decades younger named Paolo Nespoli, whose dreams of becoming an astronaut she nurtured. After five years together, intuiting that he wanted to leave but couldn’t say it, she told him never to contact her again. In 2007, a year after her death and as he prepared to enter the International Space Station, Nespoli — who is currently orbiting earth in the station again — publicly thanked her for being “the woman who made it possible to achieve this goal.”

Even as an unmarried career woman without children, Fallaci lived a very Italian life, privately devoted to her extended family and especially her parents, rooted to the Tuscan farmhouse she bought for them, and known among family and friends for her skill in that most traditional of female crafts: embroidery.

Besides her provocative interviews, Fallaci is mostly remembered for Letter to a Child Never Born”her novel about a pregnant professional woman trying to choose between a career and a child. Fallaci was against abortion and became more stridently so in her later years, but De Stefano presents letters from Fallaci to her lover to suggest that the first of Fallaci’s several miscarriages may have been the result of a botched abortion.

To Fallaci, the craft of journalism demanded contrariness. “To me, being a journalist means being disobedient,” she wrote to one colleague. “And being disobedient means being in opposition. In order to be in opposition, you have to tell the truth. And the truth is always the opposite of what people say.”

Her tragic fate was to find herself late in life hauled to court by an Italian judge on defamation charges for a series of polemics against Islam she wrote after 9/11. Her final days were spent venting at Islam, and in death her name has become — fairly or not — consistently associated with Islamophobia.

De Stefano doesn’t excuse her subject’s intolerance, but she does put it in context. According to De Stefano, Fallaci started to form her opinion of Islam in 1960, while on a world tour to research the status of women. “These veiled women are the unhappiest women in the world,” she wrote of her experience in Pakistan. “The wearer gazes out at the sky and her fellow man like a prisoner peering through the bars of her prison. This prison reaches from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean, and includes Morocco, Algeria, Nigeria, Libya, Iraq, Iran, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Indonesia. It is the immense reign of Islam.” Fallaci later told friends that the Pakistani dictator [Zulfiqar] Ali Bhutto cried when he told her he had been forced to marry his wife, a 23-year-old woman, when he was 15, and that Palestinian fighters in Lebanon refused to let Fallaci into a bomb shelter during a shelling, directing her instead to “a shed that turned out to be an explosives depot.”

In her novel Inshallah, published in 1990 after a stint covering fighting in Lebanon, one of the characters predicts that the next war wouldn’t be between capitalists and communists but that future conflicts would be channelled through religion.

In her 1970s, holed up in her memorabilia-packed New York townhouse, she watched the twin towers fall on TV and then wrote and published screeds on Islam and immigrants in Europe. Even Christopher Hitchens disavowed her. She died in Florence, unrepentantly combative and eccentric, within hearing distance of the ringing bells of the Duomo. Her stoicism in the face of cancer had led hospital workers to call her “the fakir,” an Arabic word for monk or ascetic — one who is self-sufficient and in need only of God.

–New York Times News Service

Nina Burleigh is the national politics correspondent at Newsweek magazine and the author of five nonfiction books.