How Churchill replaced Chamberlain

An engaging blow-by-blow account of the negotiations over Britain’s wartime leadership

Six Minutes in May: How Churchill Unexpectedly Became Prime Minister

By Nicholas Shakespeare, Harvill Secker, 528 pages, £20

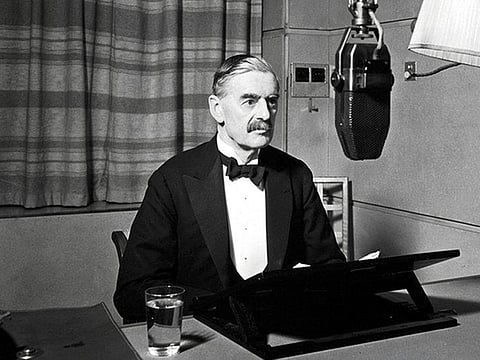

The six minutes in May that give Nicholas Shakespeare his title are those in 1940 during which the House of Commons voted on the debate following Britain’s disastrous failure in the brief Norway campaign. The prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, was not defeated in the division, but his usual majority was slashed as discontented Conservative MPs abstained or voted against him.

The idea of these minutes as critical is nonetheless misleading. As Shakespeare makes clear in this lively and well-informed rerun of how Winston Churchill became prime minister, there were many other hurdles to overcome before the change was complete, and other moments when a few minutes counted for more than the outcome of the debate.

The story Shakespeare tells is at once a familiar one. Churchill seemed an unlikely candidate to succeed. His reputation as a maverick politician, an unstable ally and an imperialist reactionary made him many enemies in parliament and left him in the political wilderness in the 1930s. In 1940, Churchill once again championed a strategic disaster. The Norway campaign was an ignominious failure, like the Dardanelles campaign in 1915.

He might well have expected it to end his brief career in Chamberlain’s war cabinet. In the end, the country and the Commons blamed Chamberlain and an uncoordinated movement began aimed at unseating the prime minister and installing a replacement.

Churchill in the end was the choice, but almost by default. There were so few men with the experience and talent to replace Chamberlain. Once Lord Halifax, the foreign secretary, had ruled himself out of the running because he feared the consequences of having to lead the war effort from the House of Lords (no one even in the First World War had had to do that), Churchill was Chamberlain’s reluctant choice. Even then the king, George VI, had a strong antipathy to Churchill and in the half hour between accepting Chamberlin’s resignation and seeing Churchill he could have changed his mind and called for Halifax. He did not, and that night, May 10, 1940, Churchill, as he later recalled, “walked with destiny”.

That the outcome might have been different is certainly possible. Shakespeare is good at reconstructing, blow by blow, the intricate negotiations and intrigues that ruled out the others and favoured Churchill.

A good deal had to happen before Chamberlain’s awkward six minutes made a Churchill premiership likely. Not least the role of the Labour party leadership in sabotaging Chamberlain’s second thoughts as the Germans broke through into Holland and Belgium that perhaps he should stay after all. Even Labour was divided, and certainly no fan of Churchill, but in the end the party executive, meeting in Bournemouth for the annual conference, voted against supporting Chamberlain, sealing his fate. Labour also confirmed that they would serve in a national government under another leader, but did not name Churchill.

What has Shakespeare brought to the established narrative? The answer lies in the microscopic detail that he has unearthed from diaries, unpublished memoirs and private papers, all of which help to make clearer the broader processes at work and to correct established errors.

He gives decent walk-on parts to characters usually absent from the history of the succession — “Baba” Metcalfe, whose relationship with Halifax, platonic or not, gave him an outlet to release his anxieties about the situation he faced; Clement Davies, the Liberal MP who organised the All Party Action Group in 1939 to try to get a new wartime leadership; and the Conservative MP Paul Emrys-Evans, who ran the “Watching Committee”, an informal cabal.

Shakespeare’s profile of Halifax helps confirm that he would have been a woeful choice as war leader, though in fairness that was Halifax’s own private view. That he was the man widely tipped to succeed seems more difficult now for historians to explain than the eventual success of his rival. Shakespeare cites Clement Attlee’s judgment: “Queer bird, Halifax, very humorous, all hunting and Holy Communion.”

Chamberlain’s position had seemed solid even by March 1940, but Shakespeare’s rebels were tunnelling under the walls. Churchill did not necessarily expect the succession, though he no doubt longed for it. He had too many enemies, and too much accumulated distrust. But his eventual achievement of the premiership was not quite the surprise that Shakespeare implies.

He had a strong following in the country, was admired by many for his stirring bellicosity in contrast to Chamberlain’s more restrained leadership, and as a potential war leader, he towered above those in high office around him. Faced with Churchill alongside him, Halifax balked at taking the premiership. Churchill became premier faute de mieux, but had there been a more obvious candidate, Churchill would have had to wait, perhaps forever. Though he felt he was walking with destiny, his wartime leadership was not preordained.

Shakespeare tells the whole story well, with sound historical sense and engaging style, but it will be a patient reader who ploughs through the detail to make out the larger narrative. At more than 500 pages, it is hard to think of any other six minutes served by so lengthy a history.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd