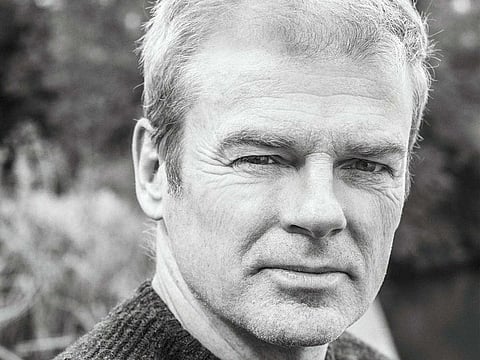

‘Curious Incident was like a gold-plated ball and chain’

Since his global bestseller, Mark Haddon has struggled to write a ‘big novel’

A third of the way through Mark Haddon’s new novel, The Porpoise, a character succumbs to a failing heart. Haddon, who spent his boyhood reading science books rather than children’s stories, has a particular nerdish fascination with how such things work, so the precise manner of this man’s demise is described over a page and a half, starting with the calcified lumps of cholesterol that have narrowed his arteries, and ending at the moment when the wall between the heart’s four chambers “is thin and ballooning and becoming weaker ... until, at last, the flesh tears and there are no longer four chambers, only one wrecked vessel of twitching flesh in which the blood pools and squelches”.

Haddon himself has recently escaped a similar fate. In February — long after the novel was finished — he was pulled into hospital for a double heart bypass. Plus, he adds punctiliously, “the redirection of a left internal mammary artery on to my coronary artery”. (He has now read two books about heart surgery, and jokes: “I could have a good crack at it myself.”)

Unlike his utterly dissipated character, Haddon, at 56, is a physically fit vegetarian, whose only symptom was something amiss on his regular runs. “I couldn’t run up big hills, then small hills, without stopping. I was exhausted for a minute, and I’d have to stop, but then I could go again.” He mentioned it to his GP, who sent him for a scan. “They said: ‘Get in here, quickly.’ I could have been that man who just keels over by the frozen fish in Sainsbury’s.”

The recovery from such an operation is long and slow. One wouldn’t know it from his energetic, incisive conversation, but he mentions a kind of “mental fog” as he gradually heals. “One of the hard things about this operation is that I can’t write, I can’t paint.”

Making art has always been as necessary to him as writing words; he has a visual, spatial imagination and always knows the minutest details of the buildings in which he places his action. The Porpoise is a departure for Haddon. His first novel written for adults, the wildly popular The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time (2003), was, in one sense at least, a suburban family drama, set between Swindon and north-west London, covering a timespan of a few days. His 2006 novel, A Spot of Bother, was a family drama set in Peterborough; The Red House (2012) was a family drama set in a holiday house on the Welsh-English border. In other senses, it is true, the books were very different from each other; but their settings and dramatis personae echoed, however distantly, Haddon’s own identity as “a straight white middle-aged man who grew up in the stultifying monoculture of Northampton in the 1960s,” as he puts it. (Haddon’s father left school at 16, but later trained as an architect. He then “made quite a lot of money specifically designing abattoirs”, so that Haddon was sent to boarding school before studying English at Oxford.)

The Porpoise, by contrast, is quite different, though it is also a family drama, among other things. It is set in the present, and in a not-quite-fixable past. And it races across the oceans: it is a book of thrilling, salt‑caked adventures that scintillate like sunlight on the surface of the sea. There are plagues and famines and sword fights with not-quite human adversaries. There are desperate escapes and terrible family separations and dramatic recognitions. It is a breathless, delightful, utterly absorbing read. It is, in fact, a reworking of Pericles, which is, by a weird coincidence, also an important reference in Ali Smith’s new novel Spring — or perhaps not so weird in these times of ours, given the play’s particular material of loss and seaborne disaster and exile.

“Yes: I finally crossed the wire into the wild,” says Haddon. “I’ve always wanted to write a big novel but found I couldn’t.” What changed, he said, was writing short stories, some of which are collected in The Pier Falls (2016). “With short stories you are allowed to take risks — you think, ‘I’ll set this one in space, why not? I might waste a month of my time but I’m not going to waste two years of my time’.” His agent remarked that he was writing short stories in which everything happened, and novels in which nothing happened. What if he found a way to put “events, real events” in a novel?

At the same time he was considering how to write “about this sprawling, diverse — I almost said fissiparous — society. How do you write about the big subjects, particularly without cultural appropriation? How do you write about exile, about not belonging, about oppression, about the stuff that literature has always been about? If you are writing contemporary realism you have to encroach upon other people’s experiences, and sometimes that feels OK — and sometimes it feels quite queasy and inappropriate. I needed to find another idiom, another space in which I could have the freedom to talk about the big themes.”

“Writers often fall into the trap of sounding like we had the whole thing mapped and just sort of brought it to fruition,” he says. In more mechanistic terms: he had been invited by Hogarth Press some years ago to contribute to a series of novelisations of Shakespeare. The terms of the project hadn’t felt quite right, but the notion kept niggling at him, and in time he landed on Pericles (which is in fact not entirely Shakespeare, in that the first nine scenes were probably by the victualler and pimp, George Wilkins).

In the first scene of that play, the hero visits the court of Antioch looking to win the hand of the king’s daughter. But the king has become obsessed with the princess, “and her to incest did provoke”. This serves only to get the plot going: she has no name, and only two lines. But there was a gap in the story into which Haddon felt he could write. And also an injustice to correct: this was a story of rape, not “incest”, as he says. Haddon reached a mass readership with The Curious Incident, a kind of whodunnit (but also a novel of manners) narrated by a teenager called Christopher, who describes himself as having “behavioural difficulties”. (These “difficulties” chime with Asperger’s syndrome — though the phrase is never used in the novel.) It has sold 10 million copies, and has been adapted into a thrilling drama by playwright Simon Stephens, which has toured internationally.

What most readers perhaps did not realise was that Haddon, by the time it was published, had been writing for nearly 20 years — mostly children’s books, many of which he also illustrated. There had also been a few acclaimed TV dramas. And no fewer than five novels for adults that he threw away. (He is a brutal discarder and destroyer and editor, “which is a polite way of saying I write dreadful first drafts, which of course no one will see”.) I wonder: did The Curious Incident feel like a vindication of a long and hard apprenticeship, or a lottery win? He laughs, and tells me about a vivid memory that he and his wife share (he is married to English don Dr Sos Eltis, who works on her laptop in the garden under the wisteria while Haddon and I talk inside). They were walking on Shotover, the hill near Oxford, just after his agent took on the book. He told her that if it sold 5,000 copies he would be delighted. “I know it’s a lottery win, but I can see, looking back, that there were factors that helped make it so popular, though they were never part of my plan. One of the things that made it globally successful was that it is not tied into the English language. The way Christopher talks can be lifted up and placed in another language and it loses almost nothing — because Christopher is not interested in the texture of words, the arrangement of words.”

That book has, of course, given Haddon the kind of financial independence that most literary novelists can only dream of. (This is translated into a comfortable though unostentatious household.) “I’ve talked to other artists who’ve had a real success. From the outside that seems very satisfying and fulfilling, but it gives you absolutely nothing to do when you wake up the next morning. You still have to create something to get you through to lunchtime, and the fact that you have done something before is sort of neither here nor there. In fact, for a lot of people it makes it harder,” he says.

The Curious Incident is “there the whole time. It’s like a gold-plated ball and chain”. It could be a full-time job, being its author, and, he says, “when I took a vow not to do any more Curious-related events my head was suddenly filled with light and space again” — though it’s difficult, putting it aside, because he doesn’t want to offend readers who still write him very touching and personal letters. On a certain level, the downside, he says, “is that I’ve not been in a position where I’ve had to write a book to pay the rent. Of course, the upside is also that I don’t have to write a book to pay the rent. I need to find a compulsion to write.” That compulsion needs to be strong: writing is hard, “like wading through quicksand, or struggling through a forest by night”. But with The Porpoise, he found that need. “It felt necessary. In my own small world, it felt necessary.”