Master of paradox

The Belgian surrealist René Magritte’s works wrench the mind with their impossible scenarios but put themselves across with a clarity that evokes an exploration of painting itself

There is a picture by Magritte that brings to mind Hobbes's vivid definition of laughter as "nothing else but sudden glory". It is painted in the Belgian's customary deadpan style and set in one of his bare-floored rooms. On the right is a sinister dark door in which a prim lace fan stands unaccountably upright. To the rear is a wallpaper sky of Magritte clouds and peerless blue. And bursting across this scene, as if to breach the cliché, is a jet of mercury that leaps merrily through the air like a lariat. The painting is called Let Out of School.

The abrupt joy of this image so perfectly embodies the title that viewers are taken by surprise. This is not the Magritte of the double-take, pictorial conundrum and visual-verbal paradox. It is a picture of euphoric release, as purely expressive as laughter itself. But this is what one learns from Tate Liverpool's huge show of 200 works, the first sizeable survey for almost a generation — Magritte is not always the riddler one had come to expect.

The master of paradox is himself a paradox. A Belgian surrealist, avant-garde and yet popular, Magritte is the straight man who paints the marvellous and bizarre in the flattest possible manner. Where the French surrealists are addicted to public outrage, he lives anonymously in his Brussels suburb, married to the same woman for 45 years, walking his Pomeranian at the same time each day.

His paintings wrench the mind with their impossible scenarios; but they put themselves across with the utmost clarity and sense. He has very little fluency as a painter, yet his work is a sustained exploration of painting itself, how it works, what it can ever show or truly say.

His pictorial vocabulary is rudimentary and restricted: the baguette, bowler hat, apple and nude, the wooden baluster, bird cage and keyhole. Everything quotidian to the Belgian clerks, in their black overcoats, who rain down from his skies, and everything, more or less, that Magritte himself could see without moving from the downstairs room where he painted, with scarcely any daylight, the window opening on to a brick wall — a blank screen for his mind's projections.

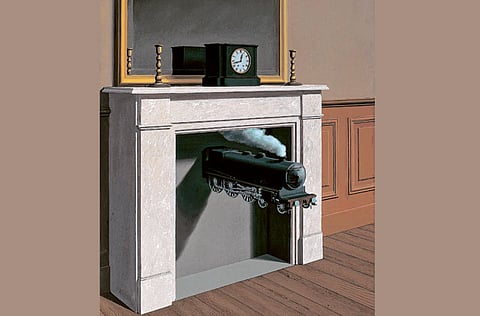

Tate Liverpool has Magritte's painting of an empty frame revealing nothing but a generic brick wall behind it. How little can a picture contain and still qualify as a picture? What is actually behind what in any painting? It has Ceci n'est pas une pipe, aka The Treachery of Images, the flat denial of the words in perfect counterpoise with the image. What can a picture be said to represent? It has the floating loaves and rearview men and day-for-night scenes where the lamps glow in the darkened streets, but up above it is still, incongruously, morning. It has the moon caught in the tree and the train steaming silently out of the fireplace, and Magritte's proverbial The Human Condition, in which the canvas placed directly in front of the window shows a picture of exactly the same view, in an endless loop of assertion and denial — what is real and what illusion, if both are depictions? Indeed, it has not one but six variations.

In later years, when his dealer went bust, Magritte rephrased old ideas for new markets (including Hollywood) without necessarily advancing much on the original. It suited his notion of himself as a craftsman rather than an artist. "I don't create paintings," he said, "I create reproductions in oil." What better description of that air of déjà vu, that blank stylistic estrangement?

Tate Liverpool has not only selected multiple variations, it has grouped them like fruit — literally in the case of the apples. This is unfortunate. What value is there in hanging his version of David's Madame Recamier alongside his version of Manet's The Balcony, each figure replaced by a coffin, a symbolic assertion of absence, mortality and the further treachery of images? The catalogue offers a hypothetical defence: "The revelation of artifice also manifests itself in Magritte's repetitions." But repetition, room after room, kills revelation.

The show's presentation is fittingly theatrical, ink and charcoal walls suggesting night and fog. A suite of surprisingly pornographic etchings is secreted behind black doors. There is some slight attempt at a maze but nothing to compare with David Sylvester's celebrated Hayward show in 1992, when the paintings apparently hung in a labyrinth of narrow sub-sections so that one rarely saw more than one at once, their power of surprise completely preserved.

But there is one intriguing advantage of seeing so many images all together, which is that the failed experiments stand out. The icing-sugar face, trompe l'oeil roses for eyes. The grisaille pictures, where the oleaginous grey paint appears disgustingly extruded. The paper collages, so indifferent they could have been made by anyone as opposed to the paintings themselves, once described as collages painted entirely by hand.

Magritte hit upon something tremendous with his textbook look, his no-style style. It is not just that the elements of his paintings appear mismatched, as in a collage; indeed, they often share elective affinities. It is more that each painting describes the scene so impersonally. The artist is not here. He does not observe these objects, these people. He has been replaced by a pictorial stenographer, a man recording something he may have heard about but never witnessed, except perhaps in a dream.

Some of the unease in Magritte's art is quite literally that — the hand about to tip the rock over the edge, the assassin behind the door. But he can touch the quick of the imagination very deeply. The Torturing of the Vestal Virgin shows a De Chirico statue, head lopped to expose bright arteries that have their horrifying echo in the metal-spiked pedestal nearby. The perpetrator has gone, leaving his weapon behind.

It is traditional to emphasise the conceptual aspects of Magritte, his mind games, his trip-wires, how they work and what they mean. But seeing his paintings in Liverpool, some of them nearly 100 years old, what strikes is just how much they make one feel, and think.

Look at The Lovers trying to kiss through their grey hoods, lips never meeting, the dry and suffocating fabric dead on the tongue. It is a masterpiece of sexual frustration. But the cornice above their heads also speaks of bourgeois imprisonment, of a couple glued together but stymied, blocked by each other. Their hoods could as well be shrouds.

"Our secret desire," wrote Magritte, "is for a change in the order of things." In disturbing the order, teasing the mind out of its old habits, turning pictures inside out, Magritte activates those secret feelings. But what is surprising is how his pictures may act as both trigger and sustaining image. The painting that gives this show its title, The Pleasure Principle, shows a man with a light for a head. It is a fine coinage, taking the light-bulb/bright-idea conceit to its physical limit. But if that were all, it would be a painted cartoon instead of a mysterious and beautiful image, the epiphany of a mind shedding light all around it, both within and without. It is the portrait of a revelation.