Ties at breaking point

Iran's expansionist policies in the Gulf have put the GCC states on edge, analysts say

The yellowish stone ramparts stand starkly against a tidal inlet close to Manama Harbour. Qal'at Al Bahrain — the Bahrain Fort — was raised seven centuries ago, guarding the azure waters of this strategic bay on the Arabian Gulf. For nearly three millennia there has been no trace of man here.

This day, during tense anti-government protests in downtown Manama, there are just a few — myself, my driver and a tall, thin, greying man, his bespectacled eyes searching for the tide now somewhere beyond the few stranded and tilting fishing boats.

"Welcome to Bahrain," he says, friendly, his English accented through years of fluent Persian. "Is this your first time in Bahrain?"

"Yes," I answer.

"Good," he says. "Welcome. Have you seen the Persian Gulf before?"

"Yes," I answer. "I have seen the Arabian Gulf many times."

His friendly features freeze. "It is the Persian Gulf," he says. "Don't you know your history?"

"Yes," I answer. "I know my history. But it's still the Arabian Gulf."

"You are not an educated man," he shouts, as my driver and I turn and walk away.

"Arabian Gulf," I taunt, unable to resist goading him. "Arabian Gulf. Arabian Gulf. Arabian Gulf."

My driver laughs. "Irani," he says in his broken English, while shouts of abuse are hurled in Persian at us as we return to our car to drive away.

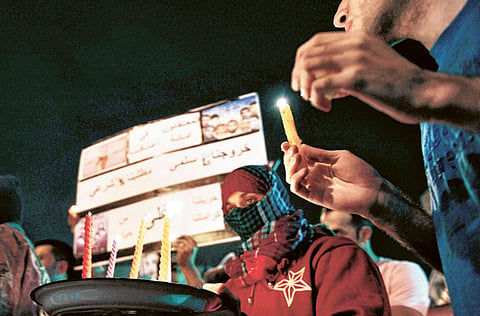

It is in Bahrain, that recent developments — weeks of anti-government protests by thousands of mostly Shiite demonstrators that brought life in Manama to a standstill — have seen relations between the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) nations and their neighbour, Iran, reach their lowest point in decades.

There is, literally and figuratively, a gulf between the two sides on ideological, political and economic standings, and relations are strained.

"The relations between Iran and the GCC have rarely been this adverse," explains Alex Vatanka, a senior Middle East analyst with IHS Janes and managing editor of Jane's Islamic Affairs Analyst and Jane's Intelligence Digest.

"There is absolutely no doubt that Tehran's support for the Bahraini protesters has exacerbated tensions. That said, ties had suffered steadfastly throughout the past few years and only Oman and Qatar can be said to have maintained cordial ties with Tehran."

If Muscat and Doha have tried to maintain cordial relations with Tehran, it is time now for them to fall in line with the rest of the GCC in showing "toughness" against Iran, notes Dr Abdul Khaleq Abdullah, professor of Political Studies at Emirates University in Al Ain.

"Toughness, yes," he says. "Qatar and Oman must fall into the GCC fold and show toughness against Iran."

Dr Abdullah says that Iran is pursuing an aggressive expansionist policy to enhance its standing regionally — a policy which is in direct conflict with the GCC nations and which will destabilise the region politically and economically if allowed to continue unchecked.

"The GCC must show a united front in turning back Iranian aggression and interference in the Gulf," he says.

That aggression has led in recent weeks to allegations of networks of spies from Tehran operating in Kuwait and Bahrain.

Recently, a Bahraini criminal court said it will try a Bahraini and two Iranians on charges of spying for Iran's Revolutionary Guards. The trio is accused of "intelligence contacts with a group of people working for a foreign country with the intention of undermining Bahrain's military, political and economic status and harming the nation's interests".

The court said that the three defendants, who were not named, were in touch with Iran's Revolutionary Guards from 2002 to April 2010 to provide them with military and economic information, along with data on military sites and industrial constructions in a bid to harm the country's national interests.

The defendants also allegedly requested money from the Revolutionary Guards in return for the military and economic information, the court said.

The trial of the two Iranians in Bahrain on espionage charges comes days after a criminal court in Kuwait condemned two Iranians and a Kuwaiti to death for their role in a spy ring broken up by the Kuwaiti authorities in May 2010.

The verdict sparked angry reactions from Kuwait and strong denials from Iran and the two countries expelled diplomats in the ensuing row.

However, Kuwait's foreign minister insisted that the spy ring working for Iran was real. Several Kuwaiti MPs, angered by Tehran's reactions, have called for the severing of diplomatic ties.

The GCC countries have been concerned about what they see as blatant Iranian interference in their domestic affairs, particularly after Tehran criticised Manama and Riyadh for the deployment of units from the Peninsula Shield, the GCC military arm, in Bahrain last month.

President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad rejected the charges by the Kuwait court and mocked the motivation behind the spying allegations. "What is there in Kuwait to spy upon?" he said.

"We are friends with both the Kuwaiti government and the people and therefore we believe that foreign hands are involved in this matter," said Ahmadinejad, referring to the United States.

"Iran categorically denies the espionage charges and the GCC states in turn point to Tehran's position on the Bahraini protests or the alleged spy rings as evidence that Iran's arm is long and that it has a hidden agenda," Jane's Vatanka says. "The GCC states by and large look at Iran as a Persian and Shiite power that wants to expand its hold wherever possible. Tehran, on the other hand, sees the GCC states as facilitators of American power projection in the Gulf region."

But that is not quite how Dr Abdullah sees it.

"There is no question that under president Khatami, relations between the GCC and Tehran were normal," he says.

"Khatami was a moderate leader and relations were warm. Since the election of President Ahmadinejad, relations have become tense. Iran is trying to assert its influence, politically and socially, throughout the Gulf region and is following an aggressive expansionist policy that needs to be stopped and countered.

"One way of doing that is by unified action by the GCC, such as we've seen recently in Bahrain with the deployment of GCC forces to assist in the security needs of a member state."

But he goes further in categorising the state of tensions between the GCC and Iran.

"We are not just at square one, we are at square zero," he says.

According to Iranian foreign minister Ali Akbar Salehi, Iran is prepared to diplomatically "resolve" differences with its Arab neighbours.

"If there are mistrusts [between Iran and the Arab countries], we can sit down and resolve them through diplomatic channels," Salehi said during a press conference translated into English by Iran's Press TV channel.

"We have only condemned the use of violence against defenceless people. This is our stance," said Salehi, insisting the governments in the region should heed the "legitimate demands" of the people.

As far as Vatanka is concerned, Qatar could have a role to play in dialling back tensions in the region.

"It could play a role, but only if the anti-Iran GCC states of Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Kuwait wanted it to. Otherwise, Qatar would risk alienating its GCC partners," he says, adding that the present level of tensions around the Arabian Gulf places Doha in an awkward position. "On the surface, such issues as the dispute over the three UAE islands occupied by Iran are said to be spoiling relations. However, the extent of the mistrust is far more fundamental and political."

Dr Abdullah, however, dismisses Salehi as being "a lame duck minister" with little or no influence. For him, the issue of the occupied Greater and Lesser Tunbs and Abu Mousa is a primary concern. He believes that talks are on in the background at a senior level to reach an agreement on the issue.

For him, the issue is the manner and the means that Tehran has been using to exert its influence in the Gulf — a destabilising policy that could prove dangerous for the GCC countries if it is allowed to continue unchecked.

He says that Iran's support for antigovernment protesters throughout the Arab world has exacerbated tensions and has but one aim — to exert Tehran's policies wherever it can, to sow discontent.

So after all that has happened in the recent months, what happens now?

"Much, if not all, in the short term will depend on what happens to the situation in Bahrain," Vatanka says. "A comprehensive crackdown on protesters in Bahrain will create an opening for Tehran and it might just decide to intervene in one way or another. I don't envisage a military conflict that brings Iran into the picture but a considerable Iranian influence in support of the Bahraini Shiites, exactly as it had played out among the Iraqi Shiites in the period after the fall of Saddam Hussain."

Vatanka says things can only be improved through political confidence-building, something Iran was able to achieve under president Khatami.

"On Ahmadinejad's watch ties have suffered," Vatanka says. "Tehran has to try to convince the GCC governments that it is not pursuing regime-toppling strategies in the various states to its south. And the GCC states have to convince Iran that they will not become part of an American front against it."

Dr Abdullah, however, sees it differently.

"There will be no improvement in relations at least for several years," he says. He points to legislative elections due in Iran in 2012 as one milestone.

"There is a presidential election due in 2014 and I think that will determine the course for relations between Iran and the GCC. Until then, I don't foresee any change," he says.

Like the tilted fishing boats lying near Bahrain Fort, Iran and the GCC, it seems, will only ply new waters when the tide comes in.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox