Tehran: In the final days of the Iranian presidential campaign, there is no clear sign of how this important event will conclude.

While the odds must be that incumbent President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, backed by much of the state apparatus, controlling the media and playing the nationalist and populist cards, will be re-elected for another four years, there is a possibility that the strongest of the opposition candidates, former prime minister Mir Hussain Mousavi, will at least force the vote to a second round.

The timing of this event could not, however, be more dramatic. Within months of the election of President Barack Obama in the US, who has offered a clear, if time-limited, olive branch to Iran, as destabilising wars rage in three neighbouring states (Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan), as the price of oil lies well below what Iran needs to sustain its economy, Iran faces both opportunities and dangers in its domestic and foreign policies.

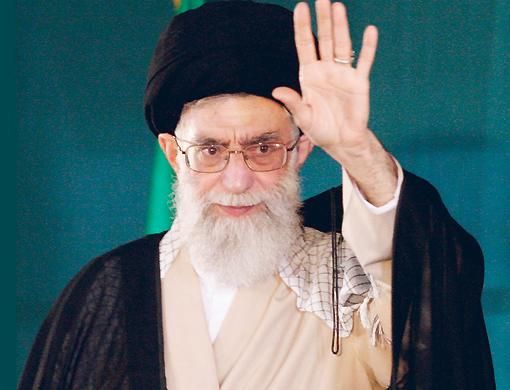

The bad news is obvious enough. First, although elected presidents have some room to speak their mind and influence policy, the ultimate power rests with Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

The call for his position to be subject to periodic review and election is one of the most explosive in contemporary Iran. He is also surrounded by a group of officials, some clergy, some from militias, who are hardened veterans of the 1980-88 war with Iraq.

While it is generally assumed that Khamenei supported the stealthy nomination of Ahmadinejad in 2005, he has made clear that he does not support the more extreme statements of his protégé.

Khamenei also keeps communication open with reformist camps.

Ahmadinejad's populist, economic, and social policies have run into difficulties, not only because of the fall in the price of oil but because of their inefficient implementation.

Secondly, Iran is changing. There is a growing sense of nationalist, rather than religious pride in the country. Third, as long as the nuclear issue exists, there is danger of a possible Israeli strike.

It is also worth noting how even as Ahmadinejad has continued his demagogy, playing a sort of variant of Italy's Silvio Berlusconi, his government has shown good judgment recently.

Domestic critics suggest that with the release of some foreign journalists, Iran is more concerned with improving its image abroad.

Iran has also sought to play a constructive role, consistent with its interests, in Iraq and Afghanistan, and has allied itself with the US in backing the Nouri Al Maliki government in Baghdad. Surprisingly, Iran supported the Status of Forces Agreement signed last December.

Meanwhile in Afghanistan, where Iranian influence has declined, it has backed the Hamid Karzai government while, in pursuit of its own interests, to all intents and purposes annexed the three provinces of Afghanistan bordering Iran.

This caution is also evident in the context of Lebanon: Iran has backed the recent compromise in the political system there, and wants to avoid new confrontations with Israel.

An interesting study released by the Israeli Ministry of Defence after the 2006 "summer war", showed that, despite Iran's close support for Hezbollah, the Lebanese group, which fired over 4,000 missiles into Israel, did not use ones manufactured in Iran.

Many of the analyses tend to start from misleading analytic and historical premises: that Iran's nuclear programme can be understood in terms of a concept of "proliferation", when in fact it should be understood in terms of Iran's search for regional influence, that Iran is a "rogue" state, when it is other states that have done far more harm to the stability of the region.

Iran is, rather, to be understood as a revolutionary state. It is a state that contains many different opinions and power centres, and which will, like all revolutions, continue to speak with two voices, those of diplomacy and of revolution.

Whatever the outcome of the election, this is the legacy that the Middle East, the West and, not least, the spirited and long suffering people of Iran will probably have to live with for quite some years to come.

Fred Halliday is ICREA Research Professor at the Barcelona Institute for International Affairs.