A peek into voters' minds

Study on ballot behaviour to be followed up in the US, Canada, Australia and five European countries

London: The general election marks the start of an extensive international study into the mind of the voter. The election campaign seems to have been going on for as long as most of us can remember. Yet between 20 per cent and 30 per cent of the electorate will make up their minds on who to vote for in these last few days, according to Dr Michael Bruter from the London School of Economics (LSE).

What's more, a significant number will change their minds when they enter the polling booth and pick up that pencil on a string. So what accounts for this apparent fickleness?

"It might be the atmosphere and the sense of responsibility that engenders. People feel freer when they're outlining their intentions to opinion pollsters. Voting makes you aware of the consequences," he says. This is only a guess at this stage, based on a pilot study of the thoughts, images and memories that go through voters' minds on entering that booth. About 600 citizens, aged from 18 to 112, took part in the pilot before and after voting in the American presidential election of 2008, the French equivalent in 2007 and the Belgian general election in the same year.

The LSE's five-year research study has begun in earnest with the general election looming. Researchers will then move on to conduct similar surveys in the US, Canada, Australia and five European countries, including France, where Bruter was born. Now a lecturer in European politics and political science, he believes the psychology of individual voters is an area that political scientists have ignored for too long.

"We haven't looked in depth at this issue since the 1960s," he says. "And then the respondents were asked simply: ‘Would you consider yourself a Labour or Conservative voter?'. Not a very interesting question." In those days, political allegiances were more entrenched, he believes. "Increasingly, people don't vote for the same party throughout their electoral life. They change their minds from one election to the next. Political science has not yet found the tools to work out why somebody who voted Labour in 1997 will vote Liberal Democrat in 2010."

Maybe that's because there's not much to work out. They're simply disillusioned with New Labour.

Floating segment

"Yes, but those who are disillusioned with Labour today may be the same ones who were disillusioned with the Tories in 1997. Will they continue to be disillusioned with politics in general? If that's the case, we have to consider why. It's not just a question of floating voters. There are voters who have different perceptions of what politics should be. They don't take the political system for granted as they might have done 40 or 50 years ago. The electorate has become more diverse, more demanding and more prone to cynicism. So we have to dig a little deeper."

A research company called Opinium has been engaged to ask questions of 2,000 voters from a cross-section of British society. "The first wave is already under way, and the second wave of questioning will take place after the polls close on Thursday evening," Bruter confides. "We want them to do it at the moment when the experience of voting is still very fresh. And we want to compare their emotions with those of postal voters."

The questions are split into four basic elements. "First, we ask about everything they can remember from past elections, including going to a polling station for the first time and the political arguments they had with family and friends," says Bruter.

"Electoral memory was what we dwelt on most during the pilots and it was noticeable how many boyfriends and girlfriends had split up because of those arguments. The second element of questioning is designed to probe a sense of electoral responsibility. Not just the duty to vote, but how they see their duty and what it means to them. Third, we want to tease out to what extent they think about what the rest of the country is doing while they're voting."

Tactical voting? "That's part of it, but there's also the protest vote voting for a party they don't really like to send a signal to their usual party."

A traditional Labour voter switching to the BNP, for instance?

"Yes, but that would only constitute a protest in political science terms if the voter does not want the BNP to win but was merely sending a signal to Labour on the issue of immigration."

And fourth, there are what Bruter calls the "funky" questions.

"We want to know what their favourite colour is, what sort of animal they feel they might resemble and what they drink when they go out."

And what on earth has any of that to do with how they vote?

"Well, we don't have major theories at this stage. These questions are exploratory. We're trying to push the frontiers of our knowledge in the field by exploring possible new relations which, if they exist, will need to be theorised and further investigated."

Book to incorporate study results

The results of all investigations from this extensive international survey will be featured in Bruter's fifth book, which has the working title ‘Inside the Mind of the Voter'. By the time it's published who knows? British voters may be facing the next general election.

Labour

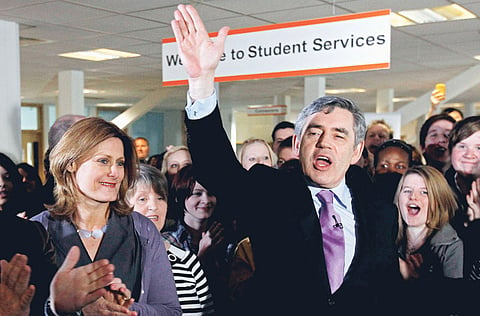

GORDON BROWN, age 59

Brown, reeling from a major gaffe on the eve of a final pre-election TV debate on Thursday, succeeded Tony Blair as British prime minister three years ago, after a decade as his ‘Iron Chancellor'.

As finance minister he was credited with overseeing an unprecedented boom in Britain's free-wheeling economy, but his reputation has been left in tatters at home by the global credit crunch.

Born in 1951, the son of a Church of Scotland minister, he grew up in Kirkcaldy, a manufacturing town north of Edinburgh, and credits his father with giving him a "moral compass".

A bright child, he went to Edinburgh University aged 16, succeeding in student politics despite a rugby accident which left him blind in one eye.

After working as a journalist and lecturer, Brown was elected to parliament in 1983 and became friends with fellow rising star Blair. Along with Peter Mandelson they created New Labour, storming to power in 1997.

But despite three election wins in a row, relations with Blair deteriorated, and he was widely seen as behind a coup which ousted his friend-turned-rival in June 2007.

While praised internationally for his economic leadership, Brown is shackled by poor people skills which saw him nicknamed ‘Mr. Bean' and fuelled reports that he bullies staff.

Those criticisms were revived this week when he was overheard calling a pensioner "bigoted," and blaming a key aide for setting up a campaign trail chat with her.

Liberal Democrats

NICK CLEGG, 43

Clegg emerged as the star of Britain's poll race after the first of three unprecedented TV debates on April 15, boosting his party — long the also-rans of British politics — into second place ahead of Labour in polls.

Clegg — named in one poll last week as the most popular British party leader since Winston Churchill, and compared by some to US President Barack Obama — took over as Lib Dem leader in December 2007.

His fervent support of the European Union and the euro and his international background certainly single him out, but his privileged past has also drawn comparisons with the Eton-educated Tory leader.

Clegg was born in 1967 and brought up in an affluent village northwest of London, before attending London's elite Westminster school alongside a young Helena Bonham Carter.

He worked briefly as a journalist and a political consultant before joining the European Commission where he worked for five years, and was subsequently a member of the European Parliament from 1999-2004.

His family history is exotic — his mother was Dutch, while his wealthy banker father was half-Russian. His wife Miriam is Spanish and their children are all bilingual. Clegg himself speaks Dutch, French, German and Spanish.

Before marrying he enjoyed the single life — in 2008 he told an interviewer that he had slept with "no more than 30" women, earning him the nickname ‘Nick Clegg-over'.

Conservative

DAVID CAMERON, 43

David Cameron, battling to become Britain's new prime minister after next week's elections, is a slick moderniser who dragged his party into the 21st century, giving it its first shot at power in 13 years.

Since becoming leader in 2005, he has transformed the centre-right Conservatives from a ‘nasty' party which lost three straight elections into a dynamic alternative to Brown's incumbent Labour.

Cameron has smoothed over historic Tory splits on Europe — a running sore since Margaret Thatcher's time — and outflanked Brown on issues like a scandal over MPs' expenses.

Some critics accuse him of being too privileged to understand the problems of ordinary Britons, while others say he lacks substance, experience and a clear ideology.

Cameron was educated at Eton, Princes William and Harry's old school, and Oxford University, where he was a member of rowdy student dining society, the Bullingdon Club, alongside future London Mayor Boris Johnson.

But Cameron was determined to make the party more centrist and populist, coining the phrase ‘compassionate Conservatism'.

His emphasis on environmentalism and fixing social problems in what he called "broken Britain" were among the clear breaks with the past.

Cameron has also used his own family to show voters the party had changed. He invited the cameras into his home to see him with his wife Samantha and three children, including his disabled son Ivan, who died last year aged six.