Vitamin A nasal drops to treat post-COVID-19 smell loss: key points

Patients share effects of post-infection loss of smell; nasal drops tested as a way out

Highlights

- Among those with “long COVID”, anosmia (lack of sense of smell, which can extend to taste) can persist for months, and even up to a year, according to one study.

- While anosmia is non life-threatening, it's fairly common; it also has a profound effect on those whose condition lingers — affecting even their emotional state and livelihood.

- Now, a team of scientists seeks to test Vitamin A drops to treat long-term anosmia.

“I was not able to smell or taste anything for two weeks after I was tested positive for COVID. I got my smell and taste back gradually. It’s been a month now and both my senses have been restored back to normal.”

“I was hospitalised for six days after contracting COVID-19. I was diagnosed with pneumonia. The loss of smell manifested five days after testing positive for COVID.”

Testimonies like these among COVID-recovered patients are common. There are rare cases, too, of long-term anosmia (te loss of smell or taste), some even lasting for at least one year, according to a new study. Others, however, also experience a distorted sense of smell — reporting pleasant-smelling things to have a foul odour.

What we know so far:

Scented candles, coffee, perfume... nothing

“I lit a scented candle…I didn’t smell anything. I brewed coffee…still no smell. I tried all sorts of perfume I have on me. Nothing. I didn’t really get emotional about it,” said Paul M., 42, a Filipino engineer in Dubai. “The loss of smell reminded me how short life is. If I had a severe COVID, and didn’t make it, my loved ones wouldn’t have seen me anymore. I was emotional about this realisation then... as I am now. I felt like I lost my sense of purpose — my 'push' in life. I just wanted to be with my family,” said Paul, a bachelor in Dubai after he sent his wife and kids back home in 2016.

WHAT IS ANOSMIA?

The term refers to partial or complete loss of the sense of smell. It may be a temporary or permanent loss. What’s the trigger? Allergies, a cold and COVID infection are some of the known conditions that irritate the nose’s lining, which can lead to anosmia. More serious conditions — such as brain tumours or head trauma — can also cause permanent loss of smell. Old age sometimes causes anosmia. Anosmia usually isn’t serious. But can affect on a person’s quality of life, lead to a loss of interest in eating, which can lead to malnutrition. More importantly, anosmia can also lead to depression because it impairs one’s ability to smell or taste pleasurable foods.

How many COVID-recovered patients are affected by anosmia?

Loss of smell affects up to 86% of COVID patients, according to a joint study by scientists in France and Canada. While it is non-life threatening, this condition causes depression, anxiety and isolation as well as changes in weight due to reduced appetite.

What can be done to treat it?

A limited study in Germany using Vitamin A nasal drops showed that those who belonged to the treated group improved twice as much as those in the untreated group, lasting at least 10 months.

What is the role of Vitamin A in restoring damaged nasal tissues?

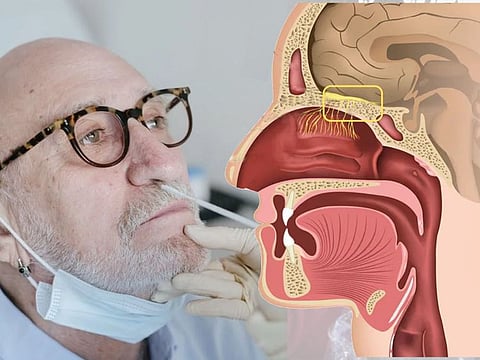

It is thought that a treatment regimen using Vitamin A nasal drops works to help repair tissues in the nose damaged by SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Now, a two-year study has kicked off to find out whether the activity of damaged smell pathways in patient’s brains increases in size, specifically following treatment with vitamin A nasal drops. This would indicate recovery. The UK team will investigate whether this hypothesis is correct.

How many people will be involved?

People who have lost their sense of smell due to a previous viral infection will be invited to join the study — via the Norfolk Smell & Taste Clinic, or through Fifth Sense, the smell and taste disorders charity. Those able to join will be randomly allocated to one of two groups: 38 patients will receive a 12-week course of nasal vitamin A drops and 19 will receive inactive peanut oil drops. Both sets of patients will receive brain scans, before and after the 12-week interval.

What changes will the investigating team look for?

First, the researchers will look for changes in the size of the “olfactory bulb” — an area above the nose where the smell nerves join together and connect to the brain — that can be measured.

Second, they will also look at activity in areas of the brain linked to recognising smells. Then, the patients will be smelling odours (roses and rotten eggs) while special brain scans are taken that use a magnet to create images.

A smell test will also measure the level of smell loss and its daily impact at the two visits (via a questionnaire). Study results will be published following peer review.

ACE2 protein receptors in the nose

SARS-CoV-2 latches on to what is known as ACE-2 protein receptors in human cells. Results of an joint study of experts led by Harvard Medical School Department of Neurobiology’s David H. Brann and Tatsuya Tsukahara reported that the ACE2 proteins the coronavirus needs to invade the cells were found on cells called “sustentacular cells”, which support the olfactory neurons — but not on the olfactory neurons themselves. Scientists think it is likely that SARS-COV-2 damaged these support system, with an immune response causing swelling of the area, though it leaves the olfactory neurons intact. It is thought that once the immune system is done dealing, the swelling subsides and the aroma molecules have a clear route to their undamaged receptors and the sense of smell returns to normal.

What if the study shows positive effect?

If it does, researchers said they will then propose a follow-on trial to establish the benefit of this treatment for these smell-loss patients.

If so, why doesn’t the sense of smell return for some?

Inflammation is the body’s response to damage. It results in the release of chemicals that destroy the tissues involved. Scientists hypothesise that, in case of severe inflammation, nearby cells get destroyed too, as “collateral” or “splash damage”. And this may explain the second stage, where the olfactory neurons are damaged.

How long does it take for olfactory neurons to recover (to revive sense of smell)?

Recovery for the olfactory neurons takes time, which also explains the much slower recovery of smell, say experts. Now the UK team will test whether vitamin A drops help the olfactory neutrons regenerate, via stem cells within the lining of the nose.

Why is there a distortion of smell, in which flowers do smell like rotten eggs?

Scientists are beginning to gain greater understanding of this phenomenon. They believe this distortion is only during the first stage — otherwise known as “parosmia”. Parosmics (people who have parosmia) typically describe the smell of coffee as “burnt” and “sewage-like”. With "nasal training", this is corrected overtime.

In the past, research into olfactory neurons had been largely neglected; this pandemic has pushed it to the forefront. One outcome: understanding about how viruses are involved in smell loss will greatly improve.

Scientists today already know that regeneration of olfactory neurons — known as “neurogenesis” — has been proven also in adults; itwas initially thought neurogenesis was restricted to embryonic and early post-natal stages in vertebrates.

Treatments for anosmia

In the past, steroids have been used to treat anosmia, but certain side effects were reported. And the evidence that they actually work is also limited. A 2014 study published in the Frontiers in Neuroscience shows many forms of smell loss are helped by a repeated, mindful exposure to a fixed set of odourants every day.

Doctors have recommended “smell training” as a therapy — by, for example, training the olfactories to smell strong odours (coffee, camphor, oils) to retrain the brain to recognise different smells. Now researchers are looking into how this would work in helping restore the ability to smell after COVID, through the so-called “physiotherapy for the nose” — and with Vitamin A nasal drops.