Sanctions are the only language Iran understands

The regime has embarked on a disruptive romp through the Arab world, using its malign influence to destabilise the region

There is a popular saying in the Middle East that, while the Iranians may not have won a war in 2,000 years, they have certainly won every negotiation. That view might require a degree of revision following Iran’s recent success on the battlefield in saving the regime of Syrian dictator Bashar Al Assad.

There can, though, be no disputing the supremacy of Iran’s negotiating skills, particularly when it comes to the contentious issue of its nuclear programme. Is there another country that could persuade six leading world powers to commit themselves to tortuous nuclear disarmament negotiations with a regime that has never actually managed to build a nuclear weapon?

Tehran would still be benefiting from the highly advantageous deal it struck with former United States president Barack Obama and other global powers in 2015 had it kept to the spirit of the agreement, whereby the ayatollahs engaged in a more constructive approach towards the outside world.

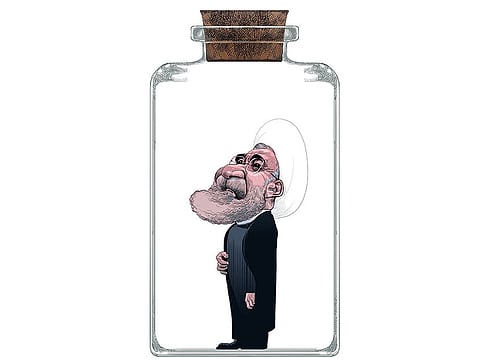

Instead, it has been business as usual for the hardliners around Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s Supreme Leader, who actually controls the country, in contrast to the so-called democratically elected government of President Hassan Rouhani. Rather than use the agreement to improve Iran’s standing in the world, as well as the economic fortunes of its beleaguered citizens, the regime has embarked on a disruptive romp through the Arab world, using its malign influence to destabilise any regime deemed friendly towards the West.

It is this reason, rather than any technical deficiencies concerning the deal itself, that has led US President Donald Trump’s entire security establishment to voice their unanimous support of their president’s uncompromising decision to withdraw from the nuclear deal, and hit Tehran with a new wave of sanctions. The likes of Defence Secretary James Mattis, who served as a front line commander in Iraq with the US Marine Corps, know only too well the extent of Iranian meddling from his experience of seeing Iranian-backed militias killing and maiming his troops.

Indeed, the full extent of Iranian duplicity in that ill-fated conflict is only now starting to come to light. The New York Times recently revealed the US Justice Department is investigating claims that several major Western-owned drug companies did business in Iraq during the war in the knowledge that medicines donated to the Iranian-controlled government in Baghdad were then sold on the black market to finance attacks on American troops.

Hopefully, the new sanctions imposed by the Trump administration will help to protect foreign multinationals against further acts of Iranian deviousness, as well as sending a strong signal to Tehran that Washington is no longer prepared to tolerate its latent hostility towards the West. Moreover, if recent experience is anything to go by, hitting Iran with sanctions actually works. The main reason Rouhani agreed to enter talks on Iran’s nuclear programme in the first place was his desperation to allow his country some respite from the punitive sanctions that had been imposed in retaliation for decades of non-compliance with its international nuclear obligations.

Now Iran seems set to suffer yet further hardship as a consequence of the new round of measures imposed by the Trump administration. The rial has already suffered a calamitous decline in anticipation of them, prompting the largest anti-regime protests since the 2009 Green Revolution.

The internal political pressure on Khamenei to change tack will only intensify as Washington ramps up the sanctions, with Iran’s vital oil exports set to be targeted in November. Applying intense economic pressure to make Tehran mend its ways is certainly a better option than military confrontation, a point Britain’s new Foreign Secretary, Jeremy Hunt, would be well-advised to take on board before he becomes too heavily invested in Europe’s anti-sanctions lobby.

Like Boris Johnson before him, Hunt seems to have succumbed to the ludicrous Foreign Office proposition, frequently aired by Sir Richard Dalton, the former British ambassador to Tehran, that the only way to change Iran’s conduct is through diplomatic dialogue.

Complete tosh, as Johnson might say. The West has tried diplomacy with Iran for nearly 40 years and achieved the square root of very little. Imposing sanctions, by contrast, has delivered quantifiable results, such as the 2015 nuclear deal. And if they worked then, there is no reason why they cannot deliver now.

— The Telegraph Group Limited, London, 2017

Con Coughlin is a noted columnist and expert on Middle East.