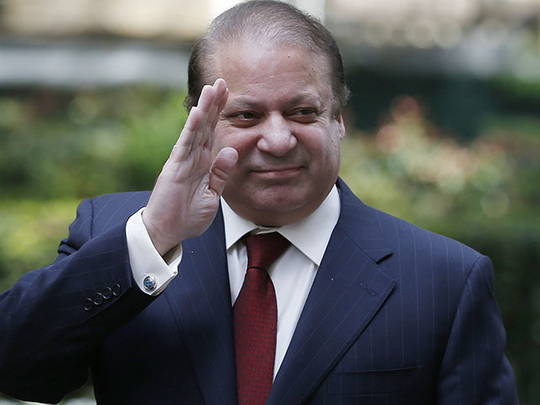

Last week’s decision by Pakistan’s main anti-corruption watchdog, the National Accountability Bureau (Nab), to file criminal charges against former prime minister Nawaz Sharif and present Finance Minister Ishaq Dar, marks a fresh chapter in the country’s history. This follows the July 28 decision by Pakistan’s Supreme Court, which dismissed Sharif as prime minister, following more than a year-long trial that was triggered by revelations of large-scale offshore wealth belonging to the former prime minister’s three children. In sharp contrast to the powerfully grim reality of at least one-third of Pakistan’s population living in abject poverty, the show of opulence in the form of properties belonging to Sharif’s children in central London’s upscale Mayfair district demands the former first family to come clean.

But the case has also thrown up an often-repeated question. Is Pakistan about to embark on a new journey to battle corruption in ways not seen before? The answer to that compelling question remains central to the future of Pakistan — a state known for being poor, even as some of its citizens become exceptionally rich. A mix of statistical and anecdotal evidence says it all. With less than one per cent of the population — or well below two million out of a population of 210 million — paying income tax, the scourge of tax evasion is nothing short of being scandalous. No wonder relatively independent research over the years has found evidence of a black economy continuing to grow significantly.

And there’s no better illustration than powerful images from the streets of Pakistan, highlighting glimpses of luxury in the midst of growing signs of poverty. Across Karachi — the largest city, parts of which were flooded after a recent spell of monsoon rains — at the traffic lights in upper-class neighbourhoods, expensive German sedans or Japanese SUVs line up one after another. The same income disparity can be experienced in upper-class supermarkets that display imported fruit such as avocado and kiwi — a kilo of which sells for twice the daily wage of an ordinary labourer.

Elsewhere too, notably in Lahore, which is the Sharif family’s home town, similarly glaring disparities are widely noticeable. Such symbols reflect poorly on Pakistan’s increasingly poor quality of governance. A failure to tax many more affluent Pakistanis has consequently led to an erosion of the state’s commitment to provide basic social services universally, noteably health care, education and employment. This obvious link between the increasing prevalence of corruption and its eventual impact on ordinary Pakistanis call for urgent measures for course correction.

Though the Nab action against Sharif, his family and Dar highlights the growing commitment of the Pakistani state to battle corruption, its just not enough. A raft of reforms is necessary to give a new direction to the Pakistani state. These must begin with enforcing Pakistan’s tax laws much more tightly and vigorously on evaders all across the country. And the battle against corruption must not just be about enforcement of tax laws.

Other areas where the battle against corruption must be fought include the institutions that directly deal with ordinary citizens such as the police, municipal and administrative authorities across the districts, utility service providers, noteably those responsibly for supplying electricity and gas, government run hospitals and last but not the least, government-run schools. The list may appear to be long and daunting, but unless the first step is taken, the journey to reform Pakistan will not even begin.

As a follow-up to last week’s action against Sharif and Dar, it is now incumbent upon Prime Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi to replace the finance minister. This is essentially not just for reasons of symbolism. More vitally, it is a step that will tell ordinary Pakistanis that the space for individuals accused of corruption is now much tighter than ever before across the echelons of the ruling structure. Once the investigations are complete, and if Dar is found innocent, his return to the Cabinet will not be an issue.

At the same time, the battle against corruption will be strengthened if the institution of the ombudsman is replicated across all the districts of Pakistan. For the public, having access to an institution where complaints of corruption are admitted and pursued for investigation, will mark a sea change from today’s environment. In addition to boosting the public’s confidence, such steps will also lift the quality of the environment for businesses across Pakistan — a definite plus towards improving the environment for doing business in the country.

In the midst of a series of challenges, it is much too easy for sceptics to forget the times when the country was surrounded by a qualitatively better environment. Less than a decade ago, in 2008, Pakistan attracted approximately $8.5 billion (Dh31.26 billion) in just one year in foreign direct investment, receipts from privatisation and foreign investments in the stock market. Today, the figure is drastically. Though in 2008, Pakistan was still faced with corruption and elements of political uncertainty caused by a lawyers’ stir, there was a palpable difference. Unlike today, the element of graft was not a source of a major controversy. The squalor surrounding present-day Pakistan needs to be tackled urgently to save the country from a likely collapse, which will surely happen if Pakistan fails to address the issue of corruption and its consequences.

Farhan Bokhari is a Pakistan-based commentator who writes on political and economic matters.