Few can recall a time when Iraq was in relative peace or not ruled by a military dictator. Generations will now digest the legacy that Saddam Hussain, the country's sixth president, bequeathed to his nation. Many more will struggle to assess and reassess the reasons why moments of grandeur were intertwined with delusional outlooks that condemned the Iraqi nation for years of outside manipulation. Such was not always the case.

A son of privilege

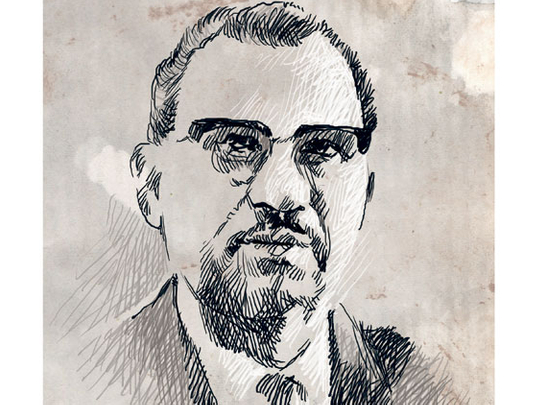

Among the more distinguished Iraqis stood Abdul Rahman Al Bazzaz, who was born to a Sunni family in Baghdad. A precocious child, the young Al Bazzaz completed elementary school and high school, graduated from the School of Law in 1934 and travelled to Britain, where he completed his law studies in 1938 at King's College. A politically awakened young man, Al Bazzaz understood the intellectual focus of pan-Arabism and the promotion of Arab nationalism. Although a product of the British education system, he supported the Rashid Ali Al Kaylani uprising against London, perceiving the colonial power for what it was, and was promptly arrested by occupation forces. Ironically, as soon as he was released from jail, Al Bazzaz was appointed dean of the Baghdad Law College but vociferous criticisms of the 1956 Israeli, British and French attacks on Egypt (the Suez War) led to his dismissal.

Al Bazzaz's central role in Iraqi contributions to the pan-Arab movement meant that he would stand against the new Abdul Karim Qasim government, which came to power in the 1958 coup d'état. After the collapse of the pro-Egyptian coup in Mosul, led by Colonel Abdul Wahhab Shawwaf on March 8, Al Bazzaz was arrested and tortured. Inasmuch as he was associated with Nasserism, the Iraqi intellectual left for Cairo upon his release and assumed the deanship of the Institute of Arab Studies at the League of Arab States. He would only return to Baghdad after the Qasim regime was toppled in 1963 (see box).

Indeed, the coup marked a turning point in Al Bazzaz's political career as his close friend, president Abdul Salam Arif, recruited the talented pan-Arabist. Several appointments followed, including ambassadorships to the United Arab Republic and the court of St James. As minister of petroleum affairs, Al Bazzaz participated in Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries' deliberations and became its secretary-general for a year. On September 6, 1965, he was named deputy prime minister and after a failed coup attempt by military officers who allegedly served president Arif, the latter invited the civilian Al Bazzaz to form a new government on September 21, 1965.

As stated above, the collapse of the first republic led by Qasim created a rare opportunity. With the Baath Party advocating Arab nationalism, power passed to a new generation, in a government led by the affable Arif. Legislative and executive powers were entrusted to the National Council for Revolutionary Command (NCRC), composed of civilian and military leaders, under the premiership of a Baathist officer, colonel Ahmad Hassan Al Bakr. Reflecting nascent revolutionary zeal, NCRC members could only agree on Arab unity, freedom and socialism as broad principles on which the new Iraq would be built.

Arguably, many Baath Party planks, from economic development to pan-Arab foreign-policy initiatives, proved impossible to implement. Dissent among party leaders translated into a chaotic environment with Arif and the dismissal of many of his military associates. On November 18, 1963, Arif wrestled power away from the NCRC and became the sole ruler.

Five months later, Baghdad introduced a new provisional constitution, which promulgated the principles of Arab unity that, strangely, necessitated that banks and major industries be nationalised. Aware of his erroneous policies, Arif invited Al Bazzaz in September 1965 to assume the mantle of the premiership. Ironically, while the erudite professor could not eradicate Arab socialist principles, he nevertheless pursued a radically different approach. Henceforth, both public and private sectors would be encouraged to buttress the Iraqi economy.

Tragically, Arif died in a helicopter accident in April 1966, which placed the prime minister at odds with military officers etching to enter the political arena. In the first joint meeting of the defence council and Cabinet to elect a president, Al Bazzaz held a plurality of one vote over two military candidates, which is why he served as interim head of state for three days.

Opposition from political groups

Nevertheless, because the president needed a two-thirds majority to win the post outright and anxious to leave their marks on Baghdad, army leaders persuaded Abdul Rahman Arif, the elder brother of the defunct president, to accept their votes. Abdul Rahman Arif appointed Al Bazzaz as premier on April 18, 1966, but was forced to resign on August 6 under pressure from various political groups. Few could tolerate the scholarly Al Bazzaz's outspokenness concerning civil and military relations.

More importantly, key officers opposed the prime minister's ceasefire accord with the Kurds on June 26, 1966, which ended a six-year armed conflict. Under the agreement, Baghdad officially recognised the Kurdish language and provided for Kurdish representation in civil government, conditions that the Sunni-dominated army officer corps rejected. Ironically, Leftist groups, including communists, denounced Al Bazzaz as a western agent. Even more comical were the accusations stemming from Nasserite Egypt, whose media engaged in a frenzy that alleged Al Bazzaz was "an enemy of Arab socialism" and that he paid lip service to the proposed union of Egypt and Iraq.

On January 24, 1969, Al Bazzaz was charged by the newly established Baathist government of participating in clandestine activities against the regime, which meant arrest, torture and imprisonment for 15 months. In 1970, he was released because of illness and went to London for treatment, where he died in 1971.

As described in his 1952 opus titled Islam and Arab Nationalism (translated by Edward Atiyah and published in English in 1965), Al Bazzaz interpreted secular Arab nationalism as a religiously acceptable phenomenon, which did not contradict the quest for Arab unity and devotion to Islam. In fact, Al Bazzaz argued that Arab nationalism and Islam were in perfect harmony because Islam was the national religion of a majority of Arabs.

Remarkably, he dismissed the notion that Christian Arabs would reject Arab nationalism on religious grounds, even though he was aware that most Arab nationalists at the time were Christians.

Al Bazzaz addressed critics by insisting that Arab nationalism must nestle in Islam because anything else would be perceived as an imported western secular ideology. For the law professor, the Arab nation was not an artificial creation formulated in response to or as a result of European influence and needed, therefore, to offer clear alternative choices.

As reported by John E. Esposito, Al Bazzaz "believed that Arabism was a natural objective reality based upon language, history and culture. In his own words: "Language, then, is the primary tenet of our national creed; it is the soul of our Arab nation". (Excerpts from Islam in Transition: Muslim Perspectives, edited by Donohue and Esposito).

Al Bazzaz concurred with Rashid Rida and Amir Shakib Arslan, who underscored the religious dimension of Arab nationalism. To accept any other interpretations, these thinkers posited, was akin to being influenced by western thinkers who confuse the "comprehensive nature of Islam" with the more limited nature of Christianity. Unlike Christianity, according to Al Bazzaz, Islam consisted of more devotional beliefs and ethical values: "Islam, in its precise sense, is a social order, a philosophy of life, a system of economic principles, a rule of government, in addition to being a religious creed in the narrow western sense." Equally important is that Al Bazzaz maintained that the spiritual versus temporal dualism that defined western Christendom was unknown in Islam.

For Al Bazzaz, therefore, Arabism and Islam were inextricably intertwined because the Arabs represented the backbone of Islam — the Quran was revealed to Arabs first, its language was Arabic, its heroes and early conquerors were all Arabs: "In fact, the most glorious pages of Muslim history are the pages of Arab Muslim history," Al Bazzaz wrote.

As reported by Esposito, although Al Bazzaz "sounded like such Islamic reformers as Rashid Rida, he in fact shifted the primary emphasis from pan-Islamic unity to Arab-Islamic unity. His primary focus was on Arab nationalism as informed by Islam, whereas he viewed pan-Islamism as a pious desire, which was unattainable." The Iraqi scholar-politician concluded that for pan-Islamism to attain its optimal outcome, it was necessary to go through Arab nationalism.

Legacy

Al Bazzaz was a strong advocate of the rule of law, the result of his tenure at the helm of power when he wished to end the domination of military officers who came to power on July 14, 1958. To his credit, he gradually civilianised authority in Baghdad, ushering in the National Defence Council that would be accountable to civilian rulers. Regrettably, while he promised to restore parliamentary life and hold elections, Iraqi army officers succeeded in denying him such goals.

Equally important, and despite his nationalist — even socialist — principles, Al Bazzaz favoured private-sector investments. He reluctantly accepted nationalisation measures but worked in earnest to mitigate their impact.

Still, perhaps his greatest legacy was the June 1966 12-point agreement to solve Iraq's Kurdish problem peacefully. It may be worth repeating that the "pact provided statutory recognition of the Kurdish nationality; recognised Kurdish as an official language along with Arabic in schools and local administration; and permitted the employment of Kurds in local administrative posts".

These were critical concessions made to ensure internal stability and while the accord granted Kurds the right to publish their own newspapers and organise political parties — along with general amnesties to those who took part in the Kurdish revolt after 1960 — it was mostly about Iraqi security. Al Bazzaz created a special Ministry for Rehabilitation and Reparation not only to compensate Kurdish victims but also to give meaning to the principles he wished his nation state to adopt.

Published on the third Friday of each month, this article is part of a series on Arab leaders who greatly influenced political affairs in the Middle East.

Dr Joseph A. Kéchichian is an author, most recently of Faysal: Saudi Arabia's King for All Seasons (2008).