The selective actor and his craft

Daniel Day-Lewis talks about his new film 'Nine', about how he gets completely immersed in the roles he plays and why he can relate to absurdity

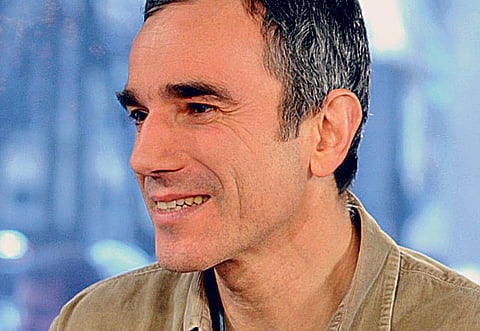

Daniel Day-Lewis is 52. His hair is peppered with grey; his voice a liquid blend of rural Irish and public-school English. He carries himself lightly but his reputation precedes him. What we have here is a double Oscar-winner and a byword for actorly obsession; a man who immerses himself so deeply in each role that he appears in perpetual danger of drowning. He broke two ribs while impersonating contorted Christy Brown in My Left Foot, lived rough in the forest before shooting The Last of the Mohicans and soldiered on through a bout of pneumonia on the set of Gangs of New York.

"The first way to kill your film is by talking about it," Day-Lewis quotes from the script of his new film, Nine. He is here to talk about the film and maybe that is OK; a necessary indignity. But talking about the film means talking about his acting and this he is famously loath to do. Unpick the method, he argues, and the magic stops working. Show us the wires and that is all we start looking for. The first way to kill an actor is to make him talk about the acting.

Nine, for the record, is the new picture from Chicago director Rob Marshall. It is an adaptation of a Broadway musical that is itself a riff on Fellini's 8 1/2. Day-Lewis headlines as Guido Contini, the Italian "maestro" who finds himself torn between the various women in his life. These women are played by a coterie of fellow Oscar-winners: Nicole Kidman, Judi Dench, Penlope Cruz and Marion Cotillard.

And what was the deal with that accent? Day-Lewis once remarked that the film he most regretted making was The Unbearable Lightness of Being because he was forced to speak English with a Czech inflection and this kept him at an arm's length from the material. Fair enough. And yet here he is doing the same thing with an Italian accent.

The actor says he can't remember saying that, exactly. "But you're right; the accent thing. It has always irked me in other films. ... I suppose I've got a small get-out-of-jail card because I like to think of Guido as one of those displaced Europeans, the sort of foreigner who speaks English better than we do. But there's no logic there, is there?" He lets rip with a startling giggle. "I can't answer your question because it's unanswerable. Denial," he says. "That's my answer. Denial!"

Day-Lewis, it transpires, giggles a good deal and it lends him a curious, boyish quality. He can also be delightfully ditsy. He keeps referring to a Michael Jackson interview he has just read in today's paper. It is only later that I realise he means George Michael.

None of which quite fits with the image. For better or worse Day-Lewis remains fixed in the public mind as the ultimate bonkers method actor — the sort of wild, selfish, free spirit who vanishes off into the wilderness for years at a stretch. In the last decade he has appeared in just four films. Off duty, he seems content to spend his days in the mountains of County Wicklow, where he has two children with his wife, the writer and film-maker Rebecca Miller.

It takes a lot to lure Day-Lewis before the cameras and he confesses that he thought long and hard before agreeing to Nine. "It wasn't a convenient time for me to go back to work," he explains loftily.

I am not sure whether to be amused or exasperated. Not a convenient time? When did he get to be so picky? "I'm not picky, quite honestly. It's simply that I recognise pretty quickly the stuff that I don't like. And I also recognise the impulse that is dragging me towards a piece of work. And perhaps as you get older, that impulse comes less often." (It strikes me, incidentally, that this is pretty much the dictionary definition of "picky").

He explains that it was different when he was younger. Back then he was fuelled by an indiscriminate ambition. So he acted in My Beautiful Laundrette, A Room With a View and Eversmile, New Jersey. He grabbed at every chance that came his way and it left him feeling hollow, scooped out. "In all fields of creativity you see the result of work that has become habit. Where the creative impulse has become flaccid or has died out altogether and yet because it is our work and our life we continue to do it."

I ask him what he loves about acting and he pauses for the longest time. "Without meaning to imply that the impulse is essentially to get away from oneself, I think it is about losing yourself in time," he says finally. "I suppose it's like when painters talk about when they begin to make marks on a canvas and then 24 hours later they're still working and there's no sense of the ticking clock and no sense of the self. The self takes care of itself through the work, through the impulse. And I find that intoxicating."

I can understand how that might work with painters or writers. But isn't film acting such an abbreviated, stop-start process? "Well, I think you've subtly brought me round to why I work the way I do. If you go to inordinate lengths to explore and discover and bring a world to life, it makes better sense to stay in that world rather than jump in and out of it, which I find exhausting and difficult. That way there isn't the sense of rupture every time the camera stops; every time you become aware of the cables and the anoraks and hear the sound of the walkie-talkies." He shrugs. "Maybe it's complete self-delusion. But it works for me."

So he stays in character from beginning to end. And how do the other actors react to this way of working? They must see him as some kind of fruitcake. Day-Lewis smiles. "A mad person, yeah. But I don't think they do. I don't think they do. I don't know but I don't think they do. I'm not ... " He hunts for the right word. "Unapproachable." So even when he is Bill the Butcher, he is still approachable? The actor giggles. "Maybe less so!"

The whole profession, he admits, is built on a paradox. Most actors are shy but this shyness is what prompts the desire to "reveal oneself". Most stars convince themselves that they are working in private, only for their faces to go before the masses and their lives to become framed as some ongoing soap opera. "And maybe it's possible to resist that but you have to catch it early on. Luckily enough, I had a shard of self-knowledge that allowed me to protect my life as far as I possibly could. ... I worry for people who don't do enough to discourage that kind of public scrutiny until it's too late." He shakes his head. "And when it's too late, it's really too late." This, I suppose, is the fate of Guido Contino in Nine, who hates the attention and craves the attention and winds up in an advanced state of disarray, lolling about in expensive hotels and singing about how miserable he is. He should have stayed more nimble. He should have moved to County Wicklow and kept hold of his soul.

Day-Lewis started the interview by quoting one line from the film, so it seems fitting to end it on another. There is a nice moment when Guido is with his wife and she looks at him and sighs. "Oh," she says. "The absurdity of being you."

Day-Lewis can relate to that: the absurdity of being him. "Absolutely," he says. "When people ask me about acting, I've often wondered whether the reason I work the way I do is an instinctual response to my sense of absurdity. And to eclipse that, I have to immerse myself more than most people. And of course that only risks making me look all the more daft." He throws up his hands. "People always ask me: ‘Isn't it strange that you have to do this or that to prepare for the work?' But really: What could be stranger than the work itself?"