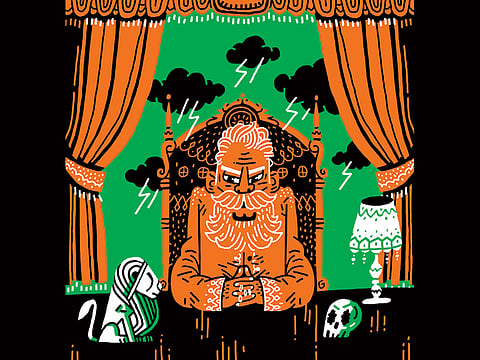

King Lear in Delhi

Contemporary India provides a fascinating backdrop for a reworking of Shakespeare’s tragedy

We That Are Young

Thanks to publishing’s conservatism, fiction set in modern India can too easily be pigeonholed: post-colonial, Raj-nostalgic, focused on slum dwellers or a globetrotting elite. We That Are Young, the doorstop debut novel from Preti Taneja, a Cambridge academic and human rights activist, ignores and subverts these stereotypes by turns.

A recasting of King Lear in today’s Delhi, the family at its centre consists of ageing patriarch Devraj, head of the multi-tentacled India Company, his daughters Gargi, Radha and Sita, right-hand man Ranjit and his son Jeet. They aren’t simply an elite; they’re practically royalty, with the Company (insistent on its capital letter) standing in for the country in more than just name, its operations covering every aspect of modern Indian life from traditional woven fabrics to coffee chains and luxury hotels. The book opens aboard a BA flight above London, with Ranjit’s illegitimate son Jivan not arriving but departing, turning his back on a somewhat passé “west” and a white girlfriend whom he derides for her attempts to “try on” his culture.

Aside from that brief in-flight scene, everything happens in India — an India markedly different from the one we are used to. Wealth creates a caste of its own, the Chinese PM displaces British aristocrats as Devraj’s hobnobbing dignitary of choice, and Tibetan-Mexican fusion restaurants underscore the reach of globalisation. Yet this has not diluted but strengthened the idea of the nation. “At heart,” Devraj expounds, “the Company is a traditional family business. This is why we have always remained within the nation’s borders. Though we do invest outside, our vision is focused here, on the Indian people.” In northern India, the wound of partition lends a special significance to borders of all kinds, and Devraj’s deceased wife is a particularly potent symbol of the violence inherent in breaching boundaries. A member of the Pandit community, she was pulled from her house into the street and killed in contested Kashmir.

This is only the most obvious iteration of the theme of porousness and contamination which, appropriately, pervades the book as a whole. There are other physical boundaries brought to our attention, though Taneja never labours the point — between business class and economy on Jivan’s flight, between those who ride in air-conditioned cars and those who walk the Delhi streets. As a child, middle daughter Radha “used to roll down the car window and stick her nose right into the city air; she used to beg for street food as they passed every cart”. Food is another rich symbol here, the outside world invited into our bodies, intoxicating and potentially contaminating. Sunburnt skin is described as “tandoored”, the sun as “a melting gulab jamun” (it is characteristic of Taneja’s intensity that she prefers metaphors to meek, hedging similes). An article in the local paper arouses both scorn and nostalgia in Jivan, its prose “cloying like Diwali sweets ... slick with the street oil it’s fried in”.

Linguistic multiplicity is an important part of the dialogue, and while not all readers will be able to parse the (pleasingly unitalicised) Hindi, it’s appropriately wrong-footing, and another instance in which the novel is worlds away from the kind of book that permits only an exotic sprinkling of swear words and familial terms.

The naturalistic dialogue is also a brilliant counterpoint to the flat, present-tense style Taneja repeatedly employs, in which the characters are like goods for sale, laid out by an advertiser to excite our interest. Interiors and clothes, the possessions that possess us, are exhaustively detailed, blurring the boundaries between active and passive, human and inanimate. This is never more pronounced than when women are the focus, such as Gargi’s engagement party, where she “was dressed in a cutwork pink lehenga bordered with gold thread. The choli was tied tight behind her neck.”

The characters respond to their constraints by lashing out on a grand scale, in increasingly desperate and self-destructive attempts to assert their own agency. But nature itself pushes back, its raging intensity both appropriately Shakespearean and a realistic manifestation of climate change – the product and humbler of hubris. Amitav Ghosh’s The Great Derangement bemoans the lack of contemporary fiction addressing this biggest of subjects, but it’s practically another character here, from the freak storm which forces Devraj to take shelter among slum dwellers, to the prototype eco-car, funded by the Company’s rotten tax gains, which he uses as a sop to Sita’s green activism.

This is not a polemical novel; it is too finely crafted, and too aware of the impossibility of purity, for that. Instead, Taneja has given us that rarest of beasts, a page-turner that’s also unabashedly political — with the complex, ambiguous, fiercely felt politics of our time.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

Deborah Smith is the translator of Han Kang’s The Vegetarian (Portobello).

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox