Scripted for new dimensions

Calligraphy is set on an innovative path by artists who go beyond old classical rules

They say: "If songs are the heard music, calligraphy is the seen music." For the artists exhibiting at the Kalimat art show at the Dubai Community Theatre and Arts Centre, the adage is unfeigned in all its mythical meaning.

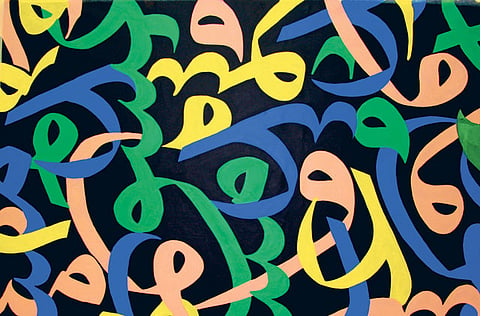

As composers of the age-old art form, they provide a contemporary makeover to calligraphy by using the subtleties of Arabic letters to create something new within the old classical rules. In this way, they free the art of beautiful writing from the rigid and conservative principles.

One of the most celebrated artists in the region, Saleh Al Shukairi, uses the 28 Arabic letters in a single composition, offering viewers to experience and feel them with "pictorial eyes" rather than with reading ones. "The abstract form takes on its own meaning and gives a unique perspective to these letters … an experience that cannot be pinned down in words," he says.

Born in 1977 in Muscat, Al Shukairi was fascinated by the Arabic script from a very young age. "I have always found Ali Hassan's artwork an inspiration," he says. The inadequate resources of books on famous calligraphers in Oman propelled him to participate in a number of workshops held locally and internationally. He finally joined the Omani Calligraphy Institute, Al Seeb, to master the flowing scripts of Roqah and Nasikh. It was there that his quest to work with a different vision, in a contemporary form, led him to explore the fluidity of Arabic calligraphy in varied forms.

Al Shukairi's work is usually termed classic, not in the sense that it relates to the most highly developed stage of a civilisation and culture but because it provides a formal yet easy admittance to the basis on which such work prevails. He lays out a comprehensive view that renders the excellence and originality of calligraphy. Some of his works are based on talisman and amulet scripts. The flowing tails, twists and turns harbour a consistency that is complicated yet simplified.

According to Al Shukairi, not the finished work but the process that leads to it is art. "In this respect it is more akin to performing arts than to most other modes of visual expression," he says.

The artist uses objects such as reed or steel pens, self-made cola pens, fragments of glass, wax and sand on handmade paper, textile, or aluminium for his work. There is a dynamic association between the flexibility and regularity of the contours and angles. "As music is a source of my motivation, I give my inspiration a free hand," he says.

A dash of colour

Having exhibited internationally — in Germany, Pakistan and the UAE as a member of the Omani Society of Fine Arts and a teacher at Oman's various Scientific Colleges of Design and Technical Colleges — Al Shukairi is striving to revolutionise calligraphy as an art form.

Other artists exhibiting at the show demonstrate an equal level of distinction. With modern, vibrant colour schemes, Kelly Izdihar Crosby gives a new vitality and an unexpected twist to calligraphy. Her technique is sort of a freestyle form of lettering that expands and enlarges the Arabic letters so that they are turned into painterly, almost three-dimensional forms, sometimes overlapped with two-dimensionality.

"I was inspired by the works of Roy Lichtenstein when I created the piece Asma ul Husna [Beautiful names of God]," Crosby explains. "I used unconventional colours to make the words stand out, especially shadows of blue and black with silver lines. The second work, Mohammad in Repetition, serves as a visual reminder of the Prophet Mohammad [PBUH]. The name is repeated and imbricated many times as intertwining circles."

Born and raised in New Orleans, Louisiana, Crosby is based in Dubai. She paints in a variety of styles and on various subjects but the ones that interest her most are landscapes, abstraction, still-life studies and floral patterns. "My art unfolds naturally as it is a collection of my experiences, my life as a Muslim and the various things that influence me," she says. Her calligraphic pieces are based on the Naskh, Thuluth and Deewani scripts.

Indian artist Khaleelullah Chemnad showcases the world's biggest piece of anatomic calligraphy representing His Highness Shaikh Mohammad Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Vice-President and Prime Minister of UAE and Ruler of Dubai. "I draw calligraphy rather than write it," says Chemnad, who began his experimentation with the art form at the age of 15, inspired by the artistic beauty of the letters in Arabic magazines. Under the guidance of his father, a famous poet in his native Kerala, he has earned himself a reputation befitting someone so passionate about his craft.

"Anatomic calligraphy is a style in which the portrait of a person is drawn using the person's name in Arabic. Sometimes, the letters and words are shaped to the object or being they represent," he explains.

The artist says he does not find a difference between Islamic art from the typical one. "Islamic art is the art of a civilisation formed by a combination of historical circumstances under the banner of Islam. Those art forms were related to architectural decoration, ceramic art and relief sculpture created with geometrical forms."

Salman Al Hajri and Julia Ibbini exploit the versatility of digital art to create emotive prints. Al Hajri utilises new media applications such as vector art. "Vector art is an ideal tool of technology for artists to reform and reshape the heritage according to modern trends and yet can retain its unique identity," Al Hajri says.

Al Hajri works within a variety of mediums and techniques as an artist, designer and researcher. His digital prints are distinguishable in terms of innovation, colour, harmony, simplicity and composition. "I attempt to create empathy with the viewers and capture their moods and feelings in the most basic form, light, movement and texture," he says.

A twist to the mundane

Ibbini's "layered" images are based upon "internal landscapes" — themes of personal and historical memory. "A work can consist of up to 50 different layers," Ibbini says. "Many pieces are created from photographs or scans of objects collected over time, such as pieces of rock, scraps of paper, old tin cans, buttons and fabric."

For these pieces, where the Arabic written word forms the basis for inspiration, Ibbini says: "I was reminded of the seeming paradox of language as both a rigid form of communication and yet also a multi-faceted form of identity and emotions that can and are interpreted in many contradictory ways."

The artists taking part also include Umm Aisha, Shabnam Majd, Aisha Abdullah Al Mehiri, Wafa Hasher Al Maktoum, Dora Mills and Hayah Taimur.

A calligrapher is always envisaged as an old religious man with a bent back. This image, however, has changed with these young artists who consider calligraphy an act of worship.

Layla Haroon is a freelance writer based in Abu Dhabi.

Kalimat is on at the Gallery of Light in the Manu Chhabria Arts Centre at DUCTAC, Mall of the Emirates, until September 13.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox