Looking at the career that renowned photographer, Pablo Bartholomew, has carved for himself today, his parents should be very proud. But it's a very different story to the one they feared could happen in 1970 when he was thrown out of school for poor grades. The 15-year-old Bartholomew's adamant refusal to apply himself to formal education led his father to abandon all hope of his son ever achieving any academic accolades. With no other options in sight, his parents decided to let him choose his own path in life.

And so Bartholomew did, in the process creating a niche in the world of the arts that he is proud of today. It is not one that has earned him riches compared to his peers, but it allows him to pursue his deepest passion - being a photographer who lives life on his own terms.

Having been raised in an artistic household, Bartholomew says his attraction to photography was inevitable. "My Burmese father, Richard, was a poet, photographer, painter and art critic. My mother, Rati, originally from Lahore, was active in the theatre. People from the arts scene were regulars at home and knowing them was enough to convince me that education isn't the only measure for success. I took up photography and, with time, dedicated my life to it."

Having earned international fame as a photojournalist (his works have been published in Time magazine, Newsweek and the New York Times), the New Delhi-based photographer now runs an online software company, Media Web, which specialises in photo database and digital archiving systems. His photographic works have been exhibited in art galleries and museums all over the world, across India and in France, Japan and America.

Work

Growing up amid cameras and a dark room at home, familiarity with the medium of photography came with ease. I found great pleasure in going through the photographic literature and encyclopedias that were a part of my father's collection.

The turning point in my life came after being thrown out of Modern School in New Delhi in 1970. I chose not to opt for formal education after Class 9, but knew that not wanting to study was a decision that would come with a certain price. Predictably, I was, in a way, socially ostracised. My parents' friends began to shun me. They considered me a bad influence on their children. My parents saw no point in pushing me although they valued education. Perhaps they thought I would end up causing more trouble for them if they forced me to study, so they let me be!

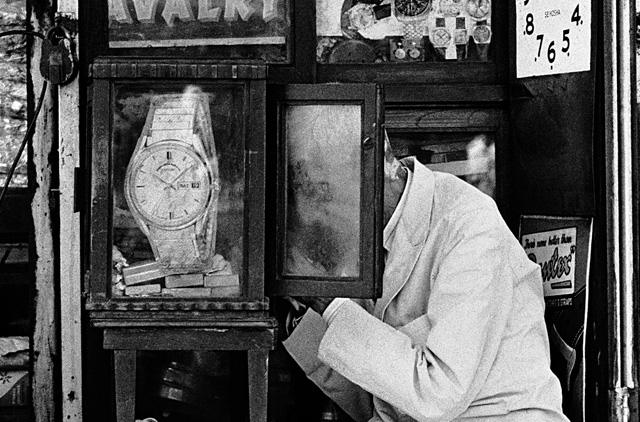

Using my father's camera, I learnt photography on my own and, by 1971, I had become a photographer. My particular interest was in capturing images of people and I would go around the city looking for interesting subjects. By 1975 I had won the World Press Photo award for a series I had done on morphine addicts in India.

I decided to leave Delhi in 1976 and went to Mumbai. Through friends there I was able to get a foothold in the Hindi film industry and into still photography; film-makers required photographs to ensure visual consistency in scenes and also for publicity purposes.

Working on the film Shatranj Ke Khiladi by noted film-maker, Satyajit Ray, took me to Kolkata, where I met British film producer, director and actor, Sir Richard Attenborough, who was playing a small role in the film. Attenborough was then later to employ me during the making of his Gandhi in 1980-81. Between assignments, I ventured into the streets taking pictures of places and people in a documentary-style. Mumbai was an escape from what I had known in Delhi and in this way it opened up new avenues for me. I had my first solo exhibition in New Delhi in 1980 and then a year later in Mumbai.

In 1982, I found I had enough savings to make a trip overseas. I developed contacts with photo agency, Gamma Liaison Network. One of my first assignments with them was for Time magazine in 1983 when I was asked to cover the Nellie ethnic conflict in Assam. Later, I worked on a Time Life book on India, part of the series called Library of Nations.

By the mid-1980s, I had branched into hard-core news photography. This took me to London, Paris and New York and to South East Asia including Sri Lanka, Nepal and India. I continued in news photography until the mid-1990s. During this period I also found time to do a documentary on the Naga tribes of north east India. Today, a lot of my personal work still deals with what touched me during my travels around the world.

During the late 1990s, photojournalism took off in a big way. Mergers and acquisitions happened and the whole business model relating to freelance photography began to change. Companies started buying photographs and photographers were put on their payroll. The result: photographers lost copyright of their images and the basis of revenue sharing.

I was unable to reconcile myself with the new business format and so formed Media Web in 1997. That was also when I rediscovered all of the work that I had done during my teens. Although it was nothing substantial, I looked at it afresh and digitised it for easy access.

Having come thus far, I now hold photography workshops and do whatever I can to teach emerging photographers in India.

Play

I spend a lot of time reading books related to photography that have more to do with seeing than actually reading. I think I read emails more seriously than literary works!

I am happy being alone, although I would not say I am a loner. I have a close set of friends from my school days who share similar interests in the fine arts.

I work without bothering about financial consequences. If something is so exciting and I feel I need to invest, I do not wait to see if it will make profit or loss.

I get inspiration from nature. I like to see light coming into my living spaces. Looking at the sky, whether it is in the morning or at night, lifts my mood.

I have always been people-oriented. People and their environment, whether within the urban or rural landscape, interest me and I like capturing such images. I get satisfaction when I see beauty in any form. Beauty is about mystery at play within the image, which could be related to photography, a painting, abstract art or just simply a woman walking on the road. I believe it is something in the character and the physique that makes a person beautiful.

Although my transition to digital photography happened smoothly and the medium will continue to evolve further, I still believe that no technology is able to replace a film roll. It has a certain quality that digital photography cannot replicate. Of course, computerisation has made things easier and more accessible, but that does not make for a great image. A photograph has to have an emotional pitch, composition and life in it.

Dream

I believe in setting benchmarks for myself and I have a road map of aims that I want to follow. I have always been and still am very clear about having setting high standards for whatever I try to achieve. And that standard need not necessarily be reflected in awards or financial gains. It has to have a personal value and to have its own visual narrative.

Having been a photographer for many years now, I am concerned about the shallowness of my profession. Today, the media is jumping all over the place trying to get grab the "big news". We photographers can feed off that and forget certain important aspects of the profession. There are not enough follow-up reports done on issues for example. Though of late there has been certain kind of activism in some instances, there are hundreds of stories that get ignored.

A rot can set in once you have been in one medium for many years and I want to re-invent myself, or go back to the years when I was fresh and naïve and there was a certain innocence in the way one looked at things.

My dreams are for the newer generation. I want my father's works, both related to his photography and his writings, to be available for everyone. When he died in 1985, I began looking through his archives. Rummaging through the documents, I discovered a sizeable collection of photographs taken by him. It was an introspective observation of life around him and was never exhibited. I wanted the pictures to get the recognition they deserved and, in 2008, the collection was displayed at the Sepia Gallery in New York, under the title A Critic's Eye.

I have now documented his art writings in the form of a book, which I plan to release this year. It is one of the most important works on Indian art, covering the works of artists such as Maqbool Fida Hussain, Ram Kumar, VS Gaitonde, A Ramachandran and Satish Gujral. These artists and my father began their careers together. That history has been lost and I am gathering it for the future generations.