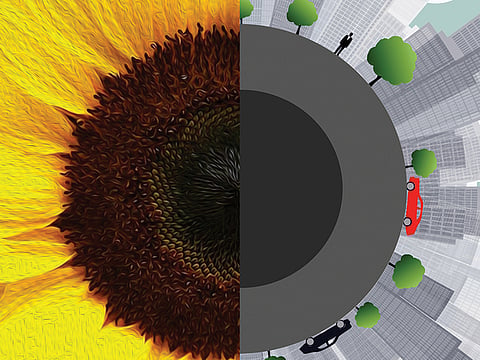

Mimicking nature can be most sincere indeed

There is so much that bio systems do organically that city planners can recreate

What if a city could function as elegantly as the natural ecosystem next door? What if it could fix carbon, store water, cool temperatures, cleanse air, build soil, support biodiversity, and remain resilient despite disturbance?

What if cities could be as high performing and as generous as nearby wildlands?

I believe this is possible, but only if we borrow the blueprints of healthy ecosystems that have been evolving in place for millennia. These systems have learnt how to thrive and even enhance their places.

Bio-mimicry is the process of emulating nature’s time-tested designs and strategies, and it’s a practice used by leading architecture and engineering firms to go beyond sustainability-as-usual.

Our built world is full of examples of innovations inspired by nature: wind turbines inspired by humpback whales, bird-safe windows inspired by spiders, self-cleaning facades inspired by lotus leaves, water purification inspired by marshes, bacteria-repelling surfaces inspired by sharks, and thin-film solar cells inspired by leaves.

Bio-mimicry has played a leading role in buildings like UK’s Eden Project, and in Zimbabwe’s Eastgate Building, an office complex in Harare that used natural ventilation strategies learnt from termites. The seven-story building, designed by Mick Pearce and engineers at Ove Arup & Partners, doesn’t need an air-conditioner, and uses 35 per cent less energy than a similar building.

But how do we apply bio-mimicry to the design of entire cities? We begin by setting our sights high, and finding metrics that are both aspirational and attainable. At Biomimicry 3.8, we measure the beneficial services provided by the local ecosystem, and then ask cities to do at least as well.

Ecological Performance Standards, or EPS, are metrics that challenge cities to meet or exceed the level of ecosystem services that the native ecosystem in that biome would provide.

Success is incredibly tangible, in metrics derived from local biology — degrees Celsius of summer cooling, tons of CO2 stored each year, tons of water stored each year, tons of air cleansed, centimetres of soil built and retained, etc.

Once standards are in place, each district would have a portion of the whole, and buildings, infrastructure, and landscapes would collectively meet citywide goals. Imagine tracking these milestones, and then celebrating them as a community.

A city that cleanses the water, cools the air, resists erosion, mitigates storms, and supports biodiversity is not just a more resilient city. It’s also a great place to live!

Take our urban village project in Lavasa, India (home to up to 50,000 people), where developed areas often suffer from massive erosion during the monsoon season. We looked at how the nearby Western Ghats forest handles up to 27 feet of water in the monsoon season with limited erosion and provided a set of the ecosystem performance service metrics for the project.

A wonderful team of landscape architects from HOK then came up with a plan to achieve it. It not only stopped erosion; it created abundant beauty.

In a climate-changed world, it’s not enough to be net zero — we have to be net positive. Especially with the most vital ecosystem service of our era: carbon sequestration.

The UN’s International Panel on Climate Change estimates surface temperatures will remain approximately constant at elevated levels for many centuries after a complete cessation of man-made CO2 emissions. That means simply stopping emissions isn’t enough.

The IPCC report goes on to note that in order to make a meaningful difference, we need to draw carbon down out of the atmosphere. Sequester it through a large net removal.

That’s the only way to actually reverse climate change.

Again, nature has hopeful and achievable answers.

Imagine a city that has committed itself to becoming a “Generous City”. It wants to sequester meaningful amounts of carbon, so it decides to use building materials that store carbon rather than releasing it (two companies — Calera and Blue Planet — are mimicking the chemical recipe of the coral reef to turn carbon dioxide from smokestacks into concrete, drywall, and aggregate).

It uses biomimetic land management practices in all its parks, to create soils that sequester carbon for centuries. It even fills its buildings with furniture made from waste methane, another biomimetic technology from NewLight Technologies. Each design intervention accumulates toward the city’s audacious carbon drawdown goal.

The same kind of thinking is applied to cleaning the air, purifying water, cycling nutrients, and cooling temperatures.

See? It’s not so hard to imagine a city that creates as much goodness as it consumes. The performance standards of today’s cities reflect yesterday’s ideals, and they’re far from sustainable.

Dreaming our next city into being begins with a simple question: what would nature do here?

The writer is the Co-founder at BiomimIcry 3.8 Co-founder, a new discipline that draws design inspiration from nature. He will be a speaker at the Dubai Sustainable Cities Summit on December 17. For more information about the summit, please visit www.dscs.ae.