In Ukraine, displaced artists create anti-war work

Contemporary artists find themselves at the forefront of storytelling mission

Lviv: When one of the most renowned visual artists in Ukraine left her home in Kyiv in the first days of the Russian attack, she went to the Lviv Municipal Art Centre. Vlada Ralko settled in among the hundreds of displaced people who sheltered at the facility last month.

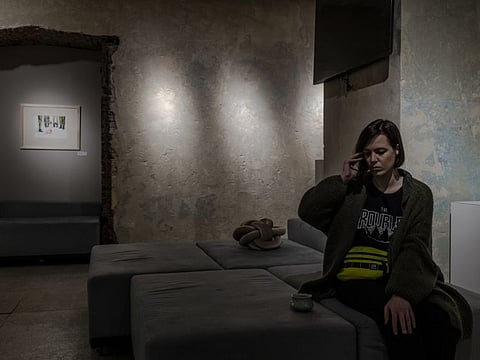

Now it is an art gallery again, showcasing the wartime work of artists from around Ukraine, including Ralko, who spent several weeks here in silence, churning out more than 100 drawings depicting the invasion.

During the same period, Stepan Burban, a rapper from Lviv, added to his soon-to-be-released album a track that amounts to a call to arms for Ukrainians. He swapped out the planned cover art for one of the recent drawings by Ralko, showing a bomb landing on a crushed womb. “The first week I felt very angry,” Burban said. “Now it is just a constant hate.”

Ukrainian daily life away from the front lines in the last two months has seen a wholesale rejection of all things Russian paired with a need to tell the world, especially Russians, what has happened here. Ukrainian contemporary artists, who for years have fought an uphill battle against a Soviet legacy of rigidity governing freedom of expression, now find themselves at the forefront of that storytelling mission.

Street posters in Lviv, which has become a gathering place for displaced artists from around the country, depict Ukrainians as white knights, noble siege defenders in medieval armour or men on horseback wielding tridents.

While the artistic reaction in metropolitan centres across Ukraine has been swift, arrivals from the east lament the absence of a similar response to Russian aggression eight years ago, when the federation attacked the Crimean Peninsula and began the war in Donbas.

Vitaliy Matukhno was a teenager in the Luhansk region of eastern Ukraine during the annexation of Crimea. He spent his formative years watching the separatists and Russian elements subdue Ukrainian authority and suppress any hint of Western culture.

“They destroyed our city from the inside so people would remember things back in the Soviet Union were better,” said Matukhno, who is now 23.

Before the attack, Matukhno was an activist, artist and publisher. He threw rave parties, planned art festivals and published a zine featuring the work of his peers. Months ago, at an abandoned television station in Lysychansk, he discovered a trove of recordings from 2002. He plans to create a compilation of scenes of life in the region before the war in Donbas.

“You have these European liberals saying, ‘We want peace,’” Matukhno said. “They are trying to create a dialogue between Russians and Ukrainians. Every Russian is guilty for what is going on right now. They are destroying my country.”

At the Lviv National Academy of Arts, students turned a campus bomb shelter into an art gallery, in part to boost morale and in part to entice apathetic and fatalistic college students to actually use the shelter when the air raid sirens wailed across the city. Upon entering, visitors are welcomed with a red bell. The tenor of the gallery shifts as one travels down narrow corridors that bear witness to what has been lost. One exhibit asks visitors to draw something they miss from homes that many cannot return to on a tiny piece of paper and slide it into a matchbox painted with the Ukrainian flag.

One student who was in Kharkiv when bombing began recorded what he could hear from his balcony for 24 hours during the conflict. Throughout the recording, chirping birds are interrupted by explosions. Over time, moments of peace produce only anxiety, knowing the other shoe will drop again shortly.

Kharkiv State Academy of Design and Arts rector Oleksandr Soboliev is now living in Lviv and working out of an office at the academy. He said at least 30 of its more than 1,030 students are missing and unaccounted for, and one has been confirmed dead. Students have been submitting posters about the war to an initiative started by the school and working to get them seen by Russians on social media.

“Nowadays we are giving much more freedom to students in regard to black humour,” he said. “In peacetime that was not allowed. Now it is the opposite, actually.” A popular theme includes the words of the Ukrainian Snake Island defenders who famously said an expletive to a Russian warship. The critical ship has since sunk, and Ukraine has claimed responsibility.

Ukraine this week released a postage stamp with a drawing picturing a soldier making an obscene gesture toward the ship. At the municipal art centre, where Ralko stayed before departing for Germany, and Burban now works on his laptop producing music, walls that once featured exhibits on pottery and Lithuanian photography are instead covered with depictions of violence.