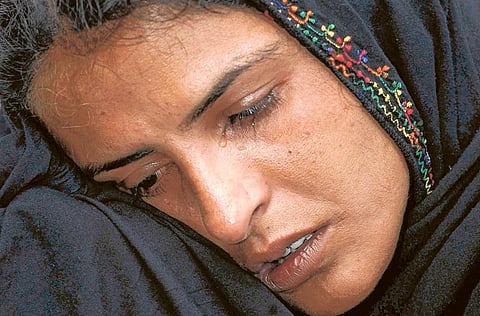

Mukhtar Mai still fighting for justice, more than a decade after gang rape

Review of case of woman assaulted at behest of village council could end 14-year struggle for justice

Islamabad: The gang-rape of Mukhtar Mai in 2002 prompted an international outcry. The 28-year-old woman, from a remote village in Pakistan, was attacked on the orders of the village jigra (council) as a punishment after her 12-year-old brother was wrongly accused of having an illicit relationship with an older woman from the dominant clan in the village. Six of the 14 men accused of the crime were given death sentences, but they appealed and five were acquitted by the Lahore high court, a ruling that was upheld by the supreme court three years ago.

Now, in an unprecedented move by the highest court in the country, a judge has ordered that the original verdict be reviewed. A judicial review of a supreme court decision is rare and represents a major breakthrough in Mai’s 14-year battle for justice. “The judge wants to review our case because they have seen something that they hadn’t seen before. I haven’t been told what they have seen, but it’s made them look again,” said Mai, now 42.

“I have been told that it’s a one in a hundred chance that a case gets reviewed by the supreme court. However, I’m scared because the supreme court is the highest court in the country. After that, there is nowhere else I can go.

“It gives me a bit of peace that at least they are listening. My prayer is that these men are punished. If they don’t get justice in the court, then I hope Allah gives me justice.”

A favourable ruling in Mai’s case “may create an impetus for rape law reform”, says Sahar Zareen Bandial, who played a key role in drafting proposed legislation to reform the rape laws, currently under review by a parliamentary committee.

Bandial, a lawyer at Lahore University of Management Sciences, said the supreme court upheld the acquittals in Mai’s case on grounds of lack of evidence - partly based on the inconclusiveness of her own testimony - and the absence of corroborating evidence such as DNA and marks indicating a struggle. “A change in the supreme court’s position on these two questions of law and evidence may carry far-reaching consequences on how the criminal justice system determines the circumstantial requirement of lack of consent in cases of rape,” Bandial said. “A change in the supreme court’s conclusion on these two questions of evidence may help address the abysmal rate of conviction in rape cases.”

Sidra Humayun, from War Against Rape Lahore , said: “In Pakistan, so few rape cases even reach the doors of the supreme court, so [the review] is a major breakthrough.

“Most people are scared to even report rape because of fears about their safety and family honour. When they are brave enough to report it, it is left to the lower courts to hear these cases, and when medical and legal support is not conducted fairly - either due to political pressure or pressure from the accused - rape cases will be disposed of.

“The police investigation is very complicated and adverse for women, particularly rape survivors. Investigating officers are not trained on how to handle rape cases and their focus is always on the survivor to provide the evidence because of the misconceptions around rape. Courts are not women-friendly environments so often any woman would prefer to quit her case as soon as possible.”

Despite numerous offers to leave Pakistan, Mai decided to remain in the area where she grew up and used the 500,000 rupees (GBP3,300) compensation she received from the government to set up the Mukhtar Mai Women’s Organisation, which includes a school and women’s refuge. “One of the biggest reasons why this has been so hard for me is because I was not educated. That is why I wanted to start up a school,” said Mai. “We have had lots of threats against the school so we have lots of security, but we have had many success stories.”

The organisation has received funding from the Virtue Foundation, an NGO with special consultative status to the UN. Her work has been admired, but it has not been without controversy, with accusations that Mai was profiting from her projects, something she denies. “It hurts me when people say this, because any woman who has been raped would rather die than make money out of it. Money won’t buy back the honour and respect I lost.

“You never forget what has happened to you, and sometimes I wonder what is the point of living. I have been fighting like this for 14 years. My health is ruined and I am exhausted. Today, for the first time in ages, I took out my sewing machine and started sewing to try and distract my mind - but all I could think of was all the difficulties I’m facing.”

Despite the physical and emotional toll, Mai remains adamant that women should speak up. “If any girl was in my situation, I would tell her that getting justice is very difficult. But we, as women, should still keep raising our voices. These court systems will have to change. But if we take this and stay quiet, it’s not good for us. Mothers, sisters, daughters, if we all unite and speak out, eventually we will get justice - if not for ourselves, for future generations.”