Karachi, Pakistan: For Sultana Javed, one of dozens of residents living without proper sanitation on her street in the Orangi Town slum, the final straw came when her toddler daughter fell into the soak pit where the family disposed of their waste.

Since moving to the Gulshan-e-Zia area of the slum in Karachi nine years earlier, Javed had poured waste into the soak pit, a porous chamber that lets sewage soak into the ground and is often used by communities that lack toilets.

Javed, whose son caught dengue fever from mosquitoes near the pit outside their home, began mobilising others among 22 families on her street to install their own sewerage system.

“We are fed up with stench of wastewater and frequent mosquito-borne diseases like malaria and dengue fever. So, we have decided to lay a sewerage pipeline in our street on a self-help basis,” Javed, 45, said.

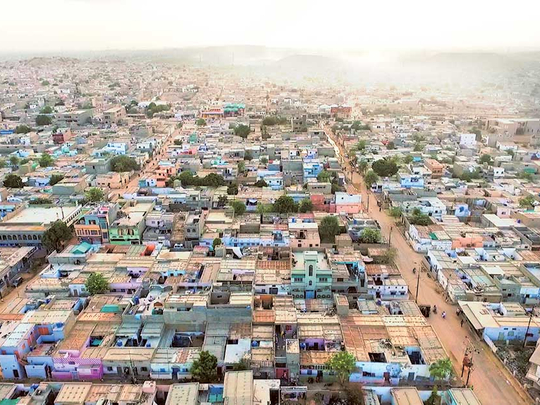

Orangi is widely cited as Asia’s largest slum and sprawls over 8,000 acres [3,237 hectares] — the equivalent of about 4,500 Wembley football pitches — in the port city of Karachi in northwestern Sindh province.

The settlement’s population exploded in the early 1970s, when thousands of people migrated from East Pakistan after the 1971 war of independence, which led to the establishment of the Republic of Bangladesh.

Today, Orangi’s population is believed to have reached around 2.4 million although no one knows the exact figure since Pakistan’s last national census was held in 1998.

Known locally as “katchi abadis”, the first informal settlements emerged in the wake of the Indo-Pakistan war of 1947, which led to a huge influx of refugees.

Unable to cope with the numbers — by 1950, the population had increased to 1 million from 400,000 — the government issued refugees with “slips” giving them permission settle on any vacant land.

Since then, land has also been traded informally, usually through middlemen who have subdivided plots of both government and private land and sold them on to the poor.

By the 1970s, when Orangi’s population exploded, the settlements had won a quasi acceptance from the government, which was unable to provide services or enough housing.

A system of upgrading and land titling was introduced, giving some residents a little more security — and community-driven upgrading projects a greater chance of success.

Activists estimate that about 60 per cent of Karachi’s total population of 15 million now live in shanty towns. Unlike in many other slums worldwide, however, the lack of services — not housing — is the major problem.

In Orangi Town, communities built two- and three-room houses out of concrete blocks manufactured locally, activists say. Each house is home to between eight and 10 people, and an informal economy of micro businesses has emerged as residents have created a livelihood working from their homes.

As the slum population has increased, residents have been cutting into the hills that surround the settlements, destroying natural bushland around it and creating swathes of barren land.

Despite the poverty, bustling markets dot the streets and surrounding industrial areas offer some employment for unskilled workers.

In 1980, the development expert and entrepreneur Akhtar Hameed Khan observed how many communities were self-organising to fill the gap in services — from building homes and schools to water delivery — and launched the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP).

Now globally renowned, the project has not only led the DIY sewerage projects that continue to expand to this day but also has built a network to manage a plethora of programmes that range from micro credit to water supply, to women’s savings schemes.

OPP’s director Saleem Aleemuddin said when activists began working in the area in 1980, the lack of sanitation was the most “obvious” and “problematic” area for residents.

While it took the OPP around six months to convince local residents to invest and pay for the installation of the first sewerage line on their street, it was not long before people were taking their lead and organising themselves.

“Since the government gets almost nothing in revenue from the slum, it therefore pays the least interest to its developments, too,” Aleemuddin said.

“In fact, people in the town now consider the streets as part of their homes because they have invested in them and that’s why they maintain and clean the sewers too.” Nearly three decades on, the OPP has not only managed to ensure that more than 90 per cent of Orangi Town’s nearly 8,000 streets and lanes have sewer pipes — all installed by residents — but has developed a network of collaborators drawing in skills from a wide variety of other nongovernment organisations.

Training to map and document drainage channels is provided to young people as are programmes that equip community architects, technicians and surveyors to work in the area. So far, say OPP activists, around 553 of the more than 2,700 Orangi Town settlements are documented.

To date, according to OPP statistics, 96 per cent of the settlement’s 112,562 households have latrines, with residents footing the total bill for the sewage system of 132,026,807 Pakistani rupees (Dh4.6 million).

‘Enough is enough’

In Gulshan-el-Zia, Javed and her neighbours decided that to kick-start their works, they needed to choose one person to lead the project and nominated 28-year-old Saleem Khan. He will not only take charge of planning but also will collect residents’ money and contributions for their new sewer and pipeline.

Khan will then work closely with OPP specialists who provide local communities with expert design advice, as well as the technical and engineering support to install the new system.

“I am sacrificing my time and energy to clean my street of the wastewater and protect people from diseases,” Khan said.

“It isn’t an easy job but I hope to get it done in the next couple of weeks with the cooperation and trust of the neighbours.” Each household plans to share the total cost of 65,679 rupees for materials to build the pipeline, which will service the entire street. Everyone in the family chips in to do the digging and laying work, including women and children.

The majority of families are home-based workers who earn around 15,000 to 20,000 rupees a month selling mainly embroidery and other cloth products at city markets.

With just a handful of local schools, most families cannot afford transport costs out of the slum and many young people work with their parents earning meagre incomes from small businesses like weaving and embroidery.

‘Everyone benefits’

Residents don’t just pay for the installation of the pipes, however, they also take responsibility for their maintenance.

Khan said manholes are to be installed at nine-metre intervals along the street to ensure residents have easy access to connections and can also monitor and maintain their pipes themselves.

Last month, Shahadat Hussain, who lives on a street that installed its own sewerage line in 2003, collected 1,000 rupees from each household on his street to replace some damaged pipes.

Nevertheless, he believes that repair of infrastructure — and the construction of secondary and main sewerage lines — is a job that local authorities should take care of.

Hussain, 29, said the government should grant residents a lease which would provide some security against eviction in return for a small fee. This would encourage them to contribute to maintenance and cleaning in the long term.

Despite repeated requests, however, the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation (KMC), has failed to do this, he said.

“We urge the provincial government to grant a lease and at least provide basic amenities including installation of secondary and main sewerage lines,” he said.

“Our homes and streets are flooded with sewage even after a light rain as there is no main line to flush it out.”

Rapid growth

According to OPP’s Aleemuddin, the city authorities now have a responsibility to step in and support slum residents who have already taken on the DIY construction of internal sewer pipes for their streets.

The sanitation programme in Orangi Town has prompted communities in 40 other slums in Sindh and Punjab provinces to install sewerage lines with technical help from the OPP, he said.

OPP believes the city should construct the secondary pipelines that collect sewage from several streets, as well as build and maintain the main trunk systems which collect and flush out sewage from entire neighbourhoods.

Nazeer Lakhani, director of Katchi Abadies (shanty town housing), acknowledged that more work is needed but said the KMC has spent 515 million rupees to build 107 main and 34 secondary sewerage lines in Orangi Town.

“We know water supply and sanitation are essential for a healthy society and we are working on provision of these basic facilities to people of Orangi Town,” he said.

For Javed, encouraging her community to work together and collaborate with the local government has given her a sense of optimism and empowerment.

“We have started feeling the positive impact of it, although our own sewer line is yet to be completed,” she said.

“I personally feel empowered and encouraged by the work I helped to initiate to get rid of the wastewater forever.”