The origins of the sensational 1932-33 conflict and its legacy continue to fascinate followers of the game.

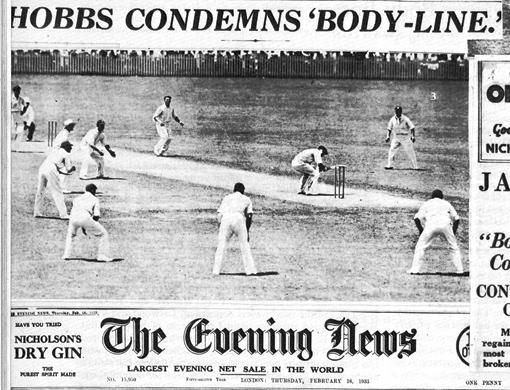

The passing of time has allowed for reassessment of the echoing storm generated by England's bruising victory over Australia in the nerve-jangling summer of 1932-33. No-one is entitled to meddle belatedly with the facts or to pretend that the bond between 'Mother country' and the 'colony' was not seriously threatened with rupture. That Test series stirred an outrage between two cricket nations well beyond any seen or heard before or since.

Douglas Jardine may well have been the only Englishman capable and willing to adhere - without the slightest wavering - to the strategy of employing strong fast bowlers (Larwood and Voce, with Bowes in one Test) to pitch short and on the line of the body - especially Don Bradman's body.

Had Bradman never been born there would probably have been no Bodyline - unless someone else, such as Stan McCabe, had gone on to make so many runs in Ashes Tests that somebody like Jardine was forced to the conclusion that unconventional albeit violent means were necessary and, at least in his mind, justified.

Of course, there had been instances of extreme aggression from fast bowlers in earlier years. Good bowlers, like good policemen, know the meaning and the importance of restraint. But, as West Indies 1970-80s leader Clive Lloyd was smilingly to say of his squad of bouncer bowlers much later, some of them "got a bit carried away". A spotlight is shone here on the great importance of captaincy.

Jardine, of course, urged his fast men to let rip, if not "get carried away". There was an important job to be done, and that was to tame the amazing Bradman and win back the coveted Ashes urn. The strategy was within the existing Laws of Cricket. The spirit of the game mattered little to Jardine as he went about his mission with military determination.

The '32-33 series shocked the world. Nothing quite like it had been seen before. It was the cold-bloodedness of England's approach that stunned the Australians. What had happened to the old alliance between cousins who had fought side by side during the Great War of 1914-18? Cricket had always been a rich source of excitement, nostalgia and entertainment, generating mutual admiration between countries. But this chap Jardine, haughty, unsmiling and obsessed, seemed to hate the land Down Under and its people.

It remains obligatory when attempting analysis to consider what went before. The younger Jardine had not been won over by Australia or its people on his 1928-29 tour, and he was not alone in resenting the bullying nature of the humourless giant Warwick Armstrong earlier in the 1920s. Armstrong had set his fast bowlers Gregory and McDonald loose on a weakened England side, a painful episode eagerly cited in '32-33 by those who chose to defend Bodyline. And earlier still, didn't Tibby Cotter and Ernie Jones batter and bruise numerous English batsmen, showing no remorse, unlike England's mighty Tom Richardson in the 1890s, who slowed down out of compassion whenever one of his rockets hurt or disabled a batsman?

Yet it was not until the extreme format of Bodyline that cricket's lawmakers realised - belatedly - the pressing need for major amendments. Even then it took a dapper little Australian delegate to the ICC (Dr Robbie Macdonald) to bring some commonsense to the matter. If England wouldn't guarantee an end to Bodyline then Australia would probably call off the (lucrative) 1934 tour. Alternatively, Macdonald suggested, they might agree to tour, but they might well bring four fast bowlers with them. It was common in those days to have two fast men, or even one and a medium-pacer to share the new ball. "Robbie Mac" having made his point with a teasing half-smile, Lord Hawke and his MCC/ICC cronies at last began to see the point.

So, first, the cluster of vulture-like short-leg fieldsmen had to be banned. This took a few months. Then the excessive bowling of bouncers had to be curtailed. This took a succession of dithering administrators a small matter of sixty years or so.

For a time, immediately post-Bodyline, such was the angelic pose adopted by or imposed upon fast bowlers everywhere that there were blushes all round should a nasty bouncer be fired down. Madcap quickies such as Laurie Nash were quietly sidelined. He, like 'Bull' Alexander, had earlier claimed that he could have stopped Bodyline in a couple of overs by bouncing the tripe out of England, but Australia's skipper, Bill Woodfull, a man of great integrity, would not countenance retaliation.

The Second World War brought a shutdown of Test cricket at an interesting time. Pitches were bland, scores were very high (unless rain fell on blessedly uncovered pitches), and fast bowlers' work was now usually unrewarding, with the bouncer still frowned upon like some anti-social disease.

Post-war, Keith Miller and Ray Lindwall changed all that. The ferocious Australian duo reactivated the short ball as a major weapon in the late 1940s, and helmetless batsmen were to suffer for several decades, into the 1980s, when the West Indians gathered in force, four fast bowlers operating at around 12 overs per tedious hour and landing very few of their deliveries in the batsman's half of the pitch. It won them lots of Test matches, but meagre admiration outside the Caribbean. Many opposing batsmen finished in hospital, and as a spectacle the game was seriously degraded. One odd upshot was that Bodyline was made to look relatively innocent in comparison.

And now, once again, cricket is a batsman's game. Pitches are covered and bland of nature; boundaries are ludicrously short; bats are heavy weapons for brute punishment that the likes of the artistic Victor Trumper or Jack Hobbs would politely have scorned; batsmen's features are concealed by helmet-visors that render them anonymous.

One thinks back to something written by cricket reporter Gilbert Mant several years after the storm of the Bodyline series: "The desire for reconciliation became so cloying that sometimes I yearned for the bad old days."

David Frith is author of BODYLINE AUTOPSY, published by ABC Books in 2002.

He has written dozens of books on both cricket in modern times and cricket of the past. His major works include My dear victorious Stod (a biography of Andrew Stoddart), Silence of the Heart (on cricketing suicides, originally published as By His Own Hand), Fast Men, Slow Men (about fast bowlers and spinners), Caught England, Bowled Australia (autobiography), The Trailblazers (the English tour of Australia in 1861-1862), The Archie Jackson Story (biography) and Bodyline Autopsy. He has also been involved in producing cricketing videos, which have been extremely successful. In 2003 he became the first author to win the Cricket Society's Book of the Year award three times, and was also a finalist in the William Hill Sports Book awards for his Bodyline Autopsy. The book also won Wisden's book of the year.