Highlights

- A black market has emerged following delays in Indian production of COVID-19 drugs

- Bureaucratic "processes and systems" seen behind delays in manufacturing and marketing approvals

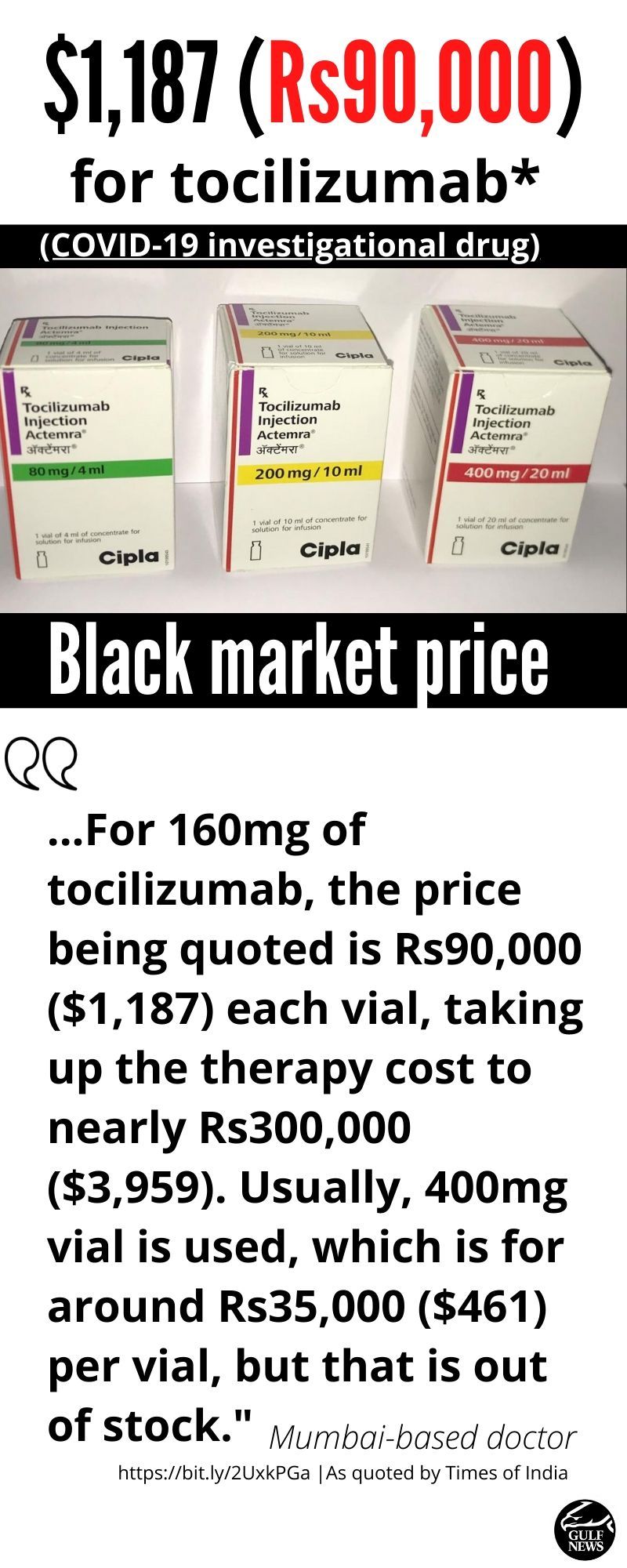

- 157% price sprike: $1,187 for each vial of COVID-19 drug in India

- Doctors trying different therapies as there's no single knock-out drug against SARS-CoV-2 yet

Dubai: A black market for COVID-19 drugs is emerging in India amid a spike in cases.

This is being compounded by regulatory reported bottlenecks that lead to production delays in already-approved drugs or therapies against coronavirus, according to latest reports.

Till now, no single drug has demonstrated a knock-out action against SARS-CoV-2, and there’s no vaccine specifically against the virus that's been approved.

Doctors around the world are trying existing drugs, mostly antivirals, that had been “repurposed” to combat the new pandemic, which has killed 408,000 people and infected 7.15 million across the world over the last 6 months.

There are at least 8 known therapies being tried in different countries, in addition to convalescent plasma therapy (CPT), against COVID-19.

The other therapies being investigated include:

- Favipiravir

- Itolizumab

- Tocilizumab

- Remdesivir

- Hydroxychloroquine

- Ritonavir + lopinavir

- Doxycycline + ivermectin

This one-by-one exploration of antiviral agents can only be done if the drugs are available. With no single therapy, and the coronavirus making a deadly run in India, doctors there use multiple options available.

Price gouging as COVID-19 cases spike

On Thursday (June 11, 2020) Indian health authorities reported nearly 10,000 fresh COVID-19 cases, with 357 new deaths. This brings to 287,000 the confirmed number of coronavirus cases in India, with 8,102 deaths.

Some Indian doctors racing against time to save lives have recommended tocilizumab and remdesivir for critically-ill COVID-19 patients.

But some doctors are now reporting price gouging.

Indian media quoted some clinicians citing “supply issues”, which they blame for the rise in black-market drugs, often at exorbitant prices.

One doctor reported a 157-per cent spike in retail price for immunosuppressive drug, tocilizumab.

The doctor, who was not identified in The Times report, stated that “for 160mg of tocilizumab, the price being quoted is Rs90,000 each vial, taking up the therapy cost to nearly Rs300,000 ($3,959). Usually, 400mg vial is used, which is for around Rs35,000 ($461) per vial, but that is out of stock.”

Supply constraints

The rheumatoid arthritis drug is also known as atlizumab, a humanised monoclonal antibody against the interleukin-6 receptor. It is also used to treat systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, a severe form of arthritis in children.

But the same “supply constraints” had been reported for remdesivir. In May, the US Food and Drug Administration granted Remdesivir emergency-use authorisation (EUA), which was soon followed by Japanese health regulators.

Indian media reported that the New Delhi government is set to procure the drug, and Indian companies are looking at manufacturing “biosimilars”. But so far, Indian hospitals do not have the drug, said doctors working at various dedicated COVID-19 hospitals.

What explains drug delays and price spike?

It’s not immediately clear what’s causing the reported “supply issues”.

The Indian media reported “pressing demand” for the two potentially “life-saving” drugs — Gilead’s remdesivir and Roche’s tocilizumab — being used to treat critically-ill patients in the country.

However, the Indian production of the said drugs are being hampered by “systems and processes”.

Meanwhile, the black market for such drugs is thriving at greatly marked-up price for generic versions, reportedly from Bangladesh.

India’s Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO) is the national regulatory body for Indian pharmaceuticals and medical devices. It also serves parallel function to the European Medicines Agency of the European Union, the PMDA of Japan, the Food and Drug Administration of the United States and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency of the United Kingdom.

But in India, there also exist state-level drug regulators.

A 2002 analysis of drug regulatory decision making in the country points to fuzzy bureaucratic functions that lead to “fragmentation and uncoordinatied delegation of powers” — eventually impeding regulatory effectiveness.

Federal and state regulators

The researchers pointed to the fact that both the CDSCO and the State Drug Regulatory Authorities (SDRAs) in India are "umbilically tied" to their parent ministries and state departments of health.

“This impedes flexibility in decision-making and autonomy in a host of areas beginning with finance, recruitment and other areas of institutional policy,” concluded the paper, published in 2015 by the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER) stated.

“Some parts of the system have been made technically autonomous such as the review of new drug applications by subject expert committees in the CDSCO. But both sets of agencies remain effectively accountable to bureaucrats in their respective parent ministries,” it stated.

Drug approvals: What’s being done?

A 2013 bill in in the Indian parliament had envisaged the establishment of a Central Drug Administration (CDA) in India, similar to the US FDA. But it still fell short of securing autonomy of the CDSCO.

The paper concuded: “The need to streamline (drug) regulatory decision-making is important both in the context of a federal division of responsibilities between the centre (central government in Delhi) and the states and to provide them with the technical and financial autonomy to function effectively.”

“Fragmentation and uncoordinated delegation of powers can impede the regulatory effectiveness of a country. Ideally, drug regulatory systems should be designed in such a way that the central co-ordinating body has overall responsibility and is accountable for all aspects of drug regulation for the entire country,” the ICRIER paper noted.

Indian media reports point to such fragmentation in the drug regulations in the country as one reason, but this could not be independently verified at the moment.

On Wednesday (June 10, 2020), Indian media reported that restricted emergency use approvals for remdesivir will be “expedited”.

Officials said the greenlight will then be given to Indian manufacturers on “rapid response basis” — but it is unlikely to be available in India this June.

On Tuesday (June 2) India’s Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO) had granted the conditional approval to Gilead Sciences to market the investigational drug after an accelerated review process.

However, Indian pharmaceutical companies are still awaiting the nod to market the drug. The result, no such locally-produced drugs are available.

Meanwhile, the absence of regulatory clearances for local manufacturers means hospitals in India have been unable to procure them.

Emergency use authorisations

Recently, US-based Gilead Sciences have given voluntary licenc e for production of Remdesivir to several Indian pharmaceutical companies — Cipla, Hetero and Jubilant.

The Indian pharma companies cannot market remdesivir in the subcontinent as they are still awaiting marketing approval from the country’s drug regulator.

Research on the efficacy of remdesivir in the treatment of COVID-19 is part of WHO’s "Solidarity" trial.

The journal Nature published research that treatment with the antiviral drug Remdesivir has been found a reduction in “viral load” and prevented lung disease in rhesus macaques monkeys infected with SARS-CoV-2.

The study supported the early use of Remdesivir treatment in patients with COVID-19 to prevent its progression.

The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) also published preliminary findings supporting the use of Remdesivir for patients who are hospitalised with COVID-19 and require supplemental oxygen therapy.

But given the high mortality rate despite the use of Remdesivir, clinicians report that therapies with an antiviral drug alone is not likely to be sufficient, future strategies should evaluate anti-viral agents in combination with other therapeutic approaches to improve patient outcomes in Covid-19, the NEJM study said.

The race is still on among COVID-19 vaccines, with 10 frontrunners and area already in different stages of human trials, with a possible “winner” (or winners) hoped to be declared in October, at the earliest.