There is good news and bad news coming out of Iraq. The good news is that election results have finally been announced by the Election Commission more than three weeks after the country's second poll since the fall of Baghdad in 2003 and the toppling of the Baath regime. The bad news is that not all parties and coalitions are happy with the outcome. Iraq finds itself, and not for the first time, wobbling between two paths; a peaceful power transition which will cement its fragile democracy, or a sudden slip into a vortex of violence and civil strife.

By UN and US standards it was a fair and transparent election with high voter turnout and, most importantly, inclusive participation. Arab Sunnis, who had boycotted the previous poll, played an important role this time by supporting a secular coalition headed by former prime minister, former Baathist and moderate Shiite leader Eyad Allawi, whose Iraqiya bloc emerged the winner on Friday.

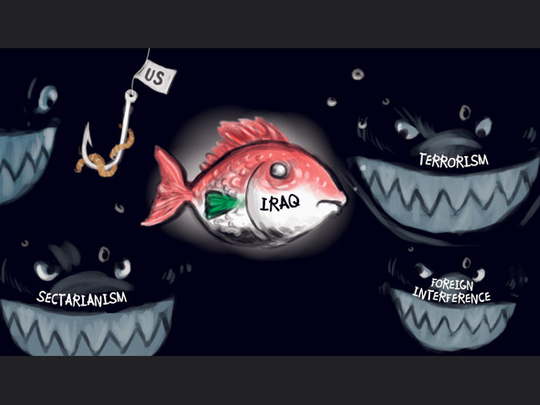

It won 91 of the 325 seats that will make up the next parliament, edging incumbent Prime Minister Nouri Al Maliki's State of Law slate, which grabbed 89 seats. It is a narrow victory for Allawi, whose front may prove to be disunited when the coalition horse-trading begins. The biggest test for Iraq's fragile democracy will be to bridge sectarian fault lines, overcome a legacy of ethnic tensions, terrorism, armed resistance to US occupation and foreign interference in the country's affairs.

Legal battle

But even as the two big rivals begin the race to win favours from smaller parties, blocs and lists, there is still a legal battle to be won. Al Maliki and other parties are contesting final results and the courts will have to step in and have their say. This could drag on for weeks and the ultimate verdict may detonate a bomb or two, both politically and physically.

But if the political process endures and the rivals manage to overcome a last-minute surprise in the form of a Federal Court ruling in response to Al Maliki's query over who has the right to form the next government (the court said it should be the biggest parliamentary coalition, not the slate with the most votes!) it will be Allawi who will be called upon by President Jalal Talabani to form a new government. But this latest legal tiff could jeopardise the entire election exercise and jettison the country into chaos and violence.

Allawi's mission will not be easy. In fact his prospects appear daunting, almost impossible. If he manages to keep his allies in line, he will have to court third-place winners, the Iraqi National Alliance, an anti-American Shiite bloc of religious factions led by cleric Moqtada Al Sadr, which has accumulated 70 seats. Even that won't be enough to secure the 163 seats he needs to form a new coalition government.

He will then have to bring in either the Kurdish Alliance, with its 43 seats, or construct a mosaic from smaller parties that include renegade Kurdish parties and others. It's a tall order.

On the other hand, his rival Al Maliki can bank on the support of his allies in the Kurdish Alliance, which would want to keep Talabani in office for a second term. He will have a tough time courting Al Sadr, with whom he has clashed in the past, but that possibility is not far-fetched. In spite of Allawi's symbolic victory, Al Maliki's chances look much better.

But that would be an oversimplification of Iraq's political realities. There are many factors involved; chief among them is the foreign dictate on the final outcome. Iran would prefer to see Al Maliki and Talabani, tested allies, make a comeback. Both are sympathetic to Teh-ran for various reasons. The US and moderate Arab countries, on the other hand, will certainly be favouring Allawi.

Iraq's Arab Sunnis, who feel disfranchised, would want Allawi's efforts to succeed. Their ambitions include seeing one of their own occupy the presidential seat.

Election results have underlined Iraq's sectarian reality. The survival of its democracy is dependent on a ‘just' allocation of key posts in the new Iraq, as cumbersome as that may be. Al Maliki's counterattack has centred on warning Iraqis of a return of Baathists to power. Indeed Allawi's coalition includes former Baathists, both generals and politicians, in addition to secular Shiites.

But Al Maliki's alternative is not so appealing either. His government has been accused of massive corruption, and its close connection to Iran has been a source of concern for the Americans who still occupy the country. If he brings in Al Sadr's INA, the West will almost certainly feel uneasy.

Iraq's democracy is unique in the Arab world. It is a product of foreign occupation, but more importantly it is now subject to regional meddling. The Americans see the elections as a critical milestone in their effort to kick-start an orderly US troop withdrawal this summer, while securing a friendly government in Baghdad. They would like to see Allawi, a moderate, pro-western, secular politician, heading that government.

The Iranians may have a different view altogether. This is where regional and local issues interweave. If Iraq is to have a peaceful transition of power in the near future, those two powers will have to come to an agreement, even if a tacit one.

This is one of the ironies of Iraq's new democracy. While Allawi and Al Maliki prepare to battle for power and parliamentary majorities, the two most influential powers will have to decide where the chips will eventually fall. The biggest fight for Iraq's future is about to commence and anything is possible.

Osama Al Sharif is a veteran journalist and political commentator based in Jordan.