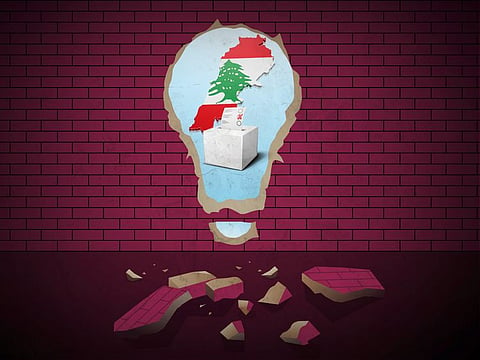

What could make or break Lebanon parliamentary elections 2022

The polls will become a big struggle for power and legacy within the Christian community

Less than one month after assuming office as Lebanon’s new prime minister, telecommunications tycoon Najib Mikati announced that parliamentary elections will take place on 27 March 2022, six weeks before their original schedule.

This was the easiest on the to-do-list of the new premier, who is unable to fulfil any of the other demands voiced by angry Lebanese, like access to their locked dollar accounts at local banks or accountability for the Beirut blast explosion that killed 230 people and torn down half the city back in August 2020.

Early elections were one of the many demands chanted during what has since been coined the October Revolution of 2019, along with better pay, services, and revamp of the sectarian political system that has been in place since the 1940s.

Mikati claims that although he is personally not responsible for any of the above, he will nevertheless try and address the grievances of the Lebanese people, securing a $1.1 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), expected to help stable the Lebanese currency which reached its lowest point in history earlier this summer, trading at 22,000 LP to the US Dollar.

He also announced that against all odds, Lebanon would go to the polls next March, ahead of presidential elections scheduled for October 2022. One of his conditions for accepting office was to stay on as prime minister both during the parliamentary and presidential vote, making him the last premier in the era of President Michel Aoun.

Muslim parties, both Sunni and Shiite, have welcomed the call for early elections, feeling no threat to their current parliamentary representation. For lack of better alternative, Saad al-Hariri’s Future Movement is expected to maintain its current bloc of 23 MPs, and it might even raise that number.

Although deprived of the financial empire that was bequeathed to him by his father, Hariri has managed to maintain his position as the prime Sunni leader of Lebanon. Nothing stuck to him, no political failure, no financial setback, and no defeat.

On the contrary, he managed to endear himself to millions by resigning from the premiership immediately after the October Revolution of 2019, and he was vocally critical of the clampdown that ensued by Lebanese security.

The same confidence applies to the two Shiite parties, Hezbollah and Amal who currently control a joint parliamentary bloc of 26 MPs (17 for Amal, 13 for Hezbollah). They are the two most powerful (and only) Shiite parties in Lebanon, boasting of a large arsenal, support from Iran, and a power base throughout the Shiite community that will make sure to vote for their leaders next March. The real competition, however, will be among Christian political parties, who are all eying the Lebanese presidency when President Aoun’s term ends in 12-months.

According to a gentlemen’s agreement dating back to 1943, known as the National Pact, the Lebanese presidency is reserved exclusively for a member of Lebanon’s Maronite Christian community. To nominate a new president, these parties would need 65 seats in the new Chamber, which currently none of them enjoy, not even the president’s Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), which controls the lion’s share of seats in the outgoing chamber (a total of 29 MPs).

To improve their standing, Christian parties are toying with the idea of reducing the voting age from 21 to 18, which will bring 280,000 additional voters to the poll (180,000 Muslims, 100,000 Christians). Young men and women form the backbone of all the Christian parties in Lebanon, and 100,000 voters can potentially tip the balance in favour of one of the four main competitors.

The Free Patriotic Movement (FPM)

Currently headed by Gibran Bassil, the ambitious son-in-law of President Aoun, the FPM is now stands as the most powerful Christian party in Lebanon, with the largest bloc in parliament and 6 out of 24 seats in the Mikati cabinet. Among other things, they control the powerful ministries of foreign affairs and defence, but were denied access to the Ministry of Interior — which Basil had coveted — which will be in-charge of handling next March’s parliamentary elections.

Basil fears that he will not be able to win the same number of seats that he currently enjoys in parliament, mainly because of the character slaughter that he has been subjected to since October 2019, much of it due to his own malpractices. When young Lebanese took to the streets two years ago, much of their outpouring was targeted against Gibran Basil, whom they accused of corruption, nepotism, and autocracy.

Basil is considered the real power-broker in the Aoun era, given that he commands absolute control over his ageing father-in-law, who relies on him to handle micromanagement of the Lebanese state. Both Aoun and Basil are blamed for the steady economic collapse that is currently underway in Lebanon, along with meltdown of the banking sector.

Hassan Diab was Basil’s pick for the premiership in January 2020, who brought him to the Grand Serail, despite the fact that he had little political experience, and kept him in office for 20 solid months, until he was forced out of office by Mikati’s naming as prime minister last September.

If Basil had his way, then he would have kept Hassan Diab at his job until October 2022, certain that he would never thing of crossing the Aounists, to which he owned his political existence.

Diab has refused to be questioned over the Beirut port probe, and so have the three ministers who are trying to petition the Lebanese justice to remove the current judge, Tarek Bitar. Basil’s support for the former premier makes him come across as an obstructer of the Lebanese judiciary, fearing that investigations will eventually target him as well, or even, reach President Aoun.

Additionally, Basil was sanctioned by the United States back in November 2020, due to his ties with Hezbollah, which makes him unacceptable at both an international and regional level. With such a record, he realises that it will be impossible to win 29 seats in the upcoming elections, explaining why he tried — with little luck — to postpone the vote, citing security conditions and financial bankruptcy of the Lebanese state.

A last-minute effort from Basil at postponing the parliamentary elections until after the presidential ones was also debunked, since nobody in Lebanon would agree to that and nor would France, which has positioned itself as guardian of the upcoming vote.

President Emmanuel Macron has visited Lebanon twice in the aftermath of the Beirut port explosion, peddling an initiative that would have led to political and administrative reforms, much to Basil’s displeasure. Among other things, Macron suggested that no party or sect gets exclusive access to any cabinet seat, calling for rotation of power among sovereignty portfolios like foreign affairs, defence, interior, and justice.

Basil rejected that, insisting on the portfolios of defence and foreign affairs for the FPM. During his Beirut visits, Macron got nothing but lip service from Lebanese leaders, who have since deposited his initiative into the dustbin of history. Last Spring, Macron took a different approach, concentrating only on parliamentary elections.

French diplomats have been encouraging members of Lebanese civil society to nominate themselves for the next elections, along with young leaders from the October 2019 Revolution, hoping that once inside the Lebanese Parliament, then they can push for real change from within the legislative branch. For that reason, the French categorically refused Gibran Basil’s attempts at calling off the elections or postponing them until after the presidential ones in October 2022.

The Lebanese Forces (LF)

Considered the second largest Christian party of Lebanon, the LF is headed by Samir Geagea, a veteran of the country’s civil war who has been at daggers-end with Michel Aoun since the 1980s. Gagegea has his own eyes set on the presidency and will move heaven and earth to prevent the country’s top job from falling into Gibran Basil’s hands.

The two men agree on practically nothing: Gagegea is highly critical of Hezbollah while Basil stands as a sound ally, Gagegea has called for Hezbollah’s disarmament while Basil has pledged to “embrace and protect the arms of the resistance.”

While Gagegea is critical of Syrian and Iranian influence in Lebanon, Basil has relied on both states for his political career, hoping that in return, they will bring him to the presidential seat at Baabda Palace, just like they did with his father-in-law back in 2016.

During the 2018 elections, Gagegea’s LF came in second after the FPM, winning an in impressive 15 seats. That feat was all the more impressive considering that unlike the FPM, Gagegea’s candidates did not have the entire state apparatus at their disposal, nor was their leader serving as president of the republic. But that bloc was self-destroyed by a collective resignation in August 2020, in light of the port explosion.

Gagegea instructed his MPs to walk out on the Chamber, hoping to win minds and hearts while expecting a total collapse of the Aoun era, with all its institutions. That did not happen, however, and although popular at a grass roots level, the collective resignation of LF parliamentarians has deprived Gagegea’s team of their right to Cabinet Office.

According to the Lebanese Constitution, ministers are chosen based on the parliamentary strength of their political parties, and given that Gagegea’s team had abandoned their parliamentary seats, they were left out of the Mikati cabinet that was formed in September.

The Lebanese Forces claim that this will not divert them from their twin objectives, of sweeping the Christian vote first, and then nominating Samir Geagea for the presidency in October. Although the first objective is highly possible, due to the LF’s popularity and the diminishing power base of the FPM, the second objective remains difficult since any future president needs support from Hezbollah.

Neither Iran nor Hezbollah will ever accept Samir Geagea as president, however, and he knows that, only too well. If he cannot make it to office, then the least he can do is make sure that the Lebanese presidency doesn’t go to Gibran Basil.

The Marada Movement

In terms of numbers, the Marada Movement is no match for either the FPM or the LF, with a tiny parliamentary bloc of three MPs. It has one strength that both lack, however, being Hezbollah’s support for its leader, Suleiman Frangieh, a good friend of both Hasan Nasrallah and Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

Frangieh is scion of a leading Maronite political family whose grandfather and namesake was president of Lebanon in the 1970s. His father Tony was murdered at the start of the country’s civil war by Samir Geagea’s militia, resulting in a deep grudge that has lasted the test of time, but might now be forgotten, albeit temporarily, to achieve a common objective of destroying Gibran Basil’s presidential ambition.

For very different reasons, both Gagegea and Frangieh dread the idea of a Basil presidency, although technically, Basil and Frangieh are both ranking members of the Hezbollah-led March 8 Coalition.

That aside, they agree on practically nothing as Frangieh considers Basil a political manipulator (a view shared privately by Hezbollah) who was never sincere in his alliance to March 8 but did it out of political necessity in order to secure the presidency for his father-in-law back in 2016.

Frangieh hopes to double his share of seats in the next elections, which would bring his seats up to six, still far too small to merit a serious parliamentary bloc. But that bloc can be empowered beyond its size by Hezbollah, Amal, and possibly, even by the LF, raising Frangieh’s chances at becoming president.

He is represented in the newly formed cabinet with two portfolios, larger than what his parliamentary representation deserves, due to an excellent relationship between him and Prime Minister Mikati. But Frangieh faces an obstacle in one of his trusted allies and party members, Yusuf Finianos, who is sanctioned by the United States and is one of the three ministers accused of “criminal negligence” in the Beirut port probe.

The Lebanese Phalange

The fourth and last of Lebanon’s major political parties, the Lebanese Phalange is headed by members of the powerful Gemayel family, who produced two of Lebanon’s former presidents, both being sons of the party’s founder, Pierre Gemayel, who is one of the founders of the modern state of Lebanon. One of his sons, Bashir was an enigmatic figure in Maronite politics who was assassinated before assuming office in 1982.

He was succeeded by his brother, Amin, who remained in office until 1988. Minutes before his term ended, Amin Gemayel appointed none other than Michel Aoun as prime minister, breaking a long observed tradition of appointing a Sunni Muslim to the Lebanese premiership.

Gemayel then went into exile in France while back in Beirut Aoun launched a dual war against his many enemies, first against Samir Geagea within the Christian community and then against the Syrian Army, which eventually defeated him and sent him to Paris, where he joined Amin Gemayel in exile.

At best, Gemayel hopes to increase his party’s share of the next Parliaminent, which would also increase his influence and give him more say on who the country’s next president would be.

If promised with political rewards, like a large number of seats in any future government, Gemayel would not mind supporting either Gibran Basil or Suleiman Frangieh for president. It all depends on how he is compensated and what his share of power will be.

Although his party is the most deep-rooted in Lebanon’s Christian history, its status today is now of a balancer within the Christian community — a party that can help make or break a presidential ambition, without attaining the presidency for any of its members.

Sami Moubayed is a Syrian historian and former Carnegie scholar. He is also author of Under the Black Flag: At the frontier of the New Jihad.