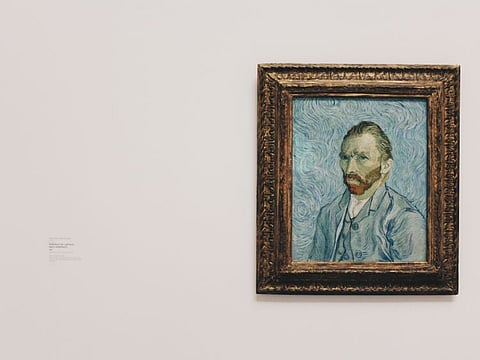

Weekend feature: The curious case of a recent self portrait of Van Gogh

The artist can generate unbridled excitement even 132 years after his death

There is a meta story within the larger story, that often reveals the ‘unimaginable’ and when it comes to Vincent Van Gogh, arguably world’s most popular artist, this holds truest.

The ‘unimaginable’ repeated itself, at National Galleries of Scotland, late Thursday afternoon last week, when Lesley Stevenson, senior painting conservator accidentally discovered a self-portrait of the Dutch impressionist on the reverse of another painting titled, ‘Head of a Peasant Woman’ drawn in 1885.

Stevenson was preparing for an upcoming exhibition at the galleries titled ‘A Taste for Impressionism: Modern French Art from Millet to Matisse’, slated to begin on July 30 and as a part of the preparation, ‘Head of a Peasant Woman’ underwent an x-ray revealing a portrait of a man uncannily similar to Van Gogh, from the reverse of the canvas.

The man who had a piercing look was dressed in a neckerchief, wide brimmed hat, and could be half seen in the greyish darkness of the composition; enough to sense that it was the maverick himself. Stevenson described the surprising revelation as a ‘shock’, peeling open another layer of the ‘anagram’ called Vincent Van Gogh.

It is strangely bewildering, how a life cut short at 37 years (1853-1890), with no artwork recognised during his lifetime, can generate such unbridled excitement even after 132 years! Pertinently, a barrage of art history scholarship has come about on Van Gogh’s life and works in last hundred years plus.

The revelation few days’ back paves way to further thrilling facts about the artist, when he made this thickly drawn portrait of a peasant woman. Covered in cardboard, stuck with glue the unseen portrait takes one back and forth in time between 1883 – 1885 when the impressionist settled in a small Dutch municipality called Neunen, in North Brabant, The Neherlands where his father was a pastor.

The Potato Eaters

In the years from December of 1883 to November of 1885, Van Gogh fell for the landscape of this northern province and most importantly with its people and their hardscrabble, defoliated life. He painted the subaltern of the village leading up to one of his greatest works, ‘The Potato Eaters’, depicting a group of impoverished, plane looking farmer family, both men and women seated on a table, in their mundane act of having a basic supper. A bulbous light hangs from the top of their table incisively examining their body language.

Van Gogh wrote, “Something peaceful, pleasant, realistic and yet painted with emotion, something brief, synthetic, simplified and concentrated, full of calm and harmony comforting like music” quotes psychologist McCay Venon and art historian Marjie L. Baughman in their essay – ‘Art, Madness and Human Interaction’. Perhaps this was written during Neunen phase, when realism was comforting for VanGogh enough to compare it with music.

His other works during these two years included titles like ‘The Rectory Garden in Nuenen in the Snow’ painted in January of 1885 and The Vicarage at Nuenen also painted in 1885’ discloses a somber tone of self-exploration and solitude.

What was he searching for? Was it mere introspection? Were these paintings part of his healing from his disastrous failure of early life goals, “religious salvation of coal miners”? Whatever this phase exactly was, it was deeply related to his intensely complex mind, leading up to the last phase of his life at Arles in France.

To decode the compelling words ‘calm and comfort’, one must decipher this phase, one which had begotten arguably his greatest work ‘The Potato Eaters’. Like its famous cousin, ‘Head of a Peasant Woman’ too may have been a source and reason for a calmer mind for it featured Gordina de Groots, a young peasant woman with whom Vincent became friends.

In a letter to Theo, his younger brother and lifelong confidante, the artist confessed his growing interest and almost ‘anytime walk in’ association with the de Groot’s, describing how beautiful the family looked as they sat down to have their meal on the evening at a corner of their house filled with natural light.

He even termed the scene as “astonishingly beautiful”. More literally, Van Gogh expressed the desire to paint two women of this family describing their beauty as that of a “green soap”.

Like so many aspects of Van Gogh’s life, we remain in dark about the ‘green soap’ reference. The next one knows that young Gordina had sat for Van Gogh several days at his studio in Neunen. She became pregnant close to these days of modelling and Van Gogh was accused by the local sexton for her pregnancy.

He denied, letting them know the name of the father of Gordina’s unborn, an information she had confided in Van Gogh during their frequent interaction at the studio. It was the summer of 1885. Once again the impressionist painter wrote, “It is not only yielding to one’s impulses that one achieves greatness, but also patiently filing away the steel wall which separates what one feels and what one is capable of doing”.

These contemplative words are almost inferences. It was surely impulse that had made him stay back at this provincial town otherwise lackluster with the solitary high note of having known the De Groots in the centrality of which lay his friendship with Gordina. By 1886 Van Gogh had moved to Paris and this self-portrait on the reverse was thought to be painted after he had settled there.

Although a section of the art historians has always justified Vincent’s use of the same canvas to his financial inadequacy, still there is room for interpretation about the finding of last week. A Pandora’s box of sorts opens up.

Did this self-portrait much like his letters was an add on to his to his compensatory mechanism, an answer to his inability to arouse critical attention or his materialistic insufficiency and prolong loneliness or just another impulsive experimentation that stemmed from his inability to hire a model. Was this art produced out of impulse, a soul connect that he felt with Gordina?

Evidently in his letters written to Theo during the creative phase of ‘The Potato Eaters’ which is same as that of ‘Head of a Peasant Woman’ Van Gogh emphasizes how his paintings are not ‘mere act of aesthetics’ but a process of ‘locating himself’ in a special world.

A routine representation of his feelings and dailiness, the letters also show, how Vincent perceived his art, often calling them ‘homes’, an identification which he worded in a way as if the working class that is the miners, labourer, and peasants were an extension of himself, rendering that subjects and the painter do merge.

Would it be improbable to interpret this self-portrait drawn on the idea of this ‘merger’ using the reverse of the canvas a remembrance of ‘impulses’ read association of his Neunen days.

The Paris phase beginning in January of 1886 saw the ‘psychodynamic’ outburst of Van Gogh’s creativity. In the two years, he drew some twenty other self-portraits and more during his last years of illness at Arles. I would associate this self-portrait as a part of this intense creativity, while he was getting surer about his painter self.

Significantly more paintings had earlier been found on the reverse of his self-portraits indicating that he didn’t care much about what was already drawn.

Afterword

Following deaths of both the brothers’ in a gap of just six months, first Vincent’s and later Theo’s, Johanna Van Gogh –Bonger, wife of Theo and sister in law of the artist, was left with 200 odd paintings of Van Gogh, some little assets and an infant to raise. In coming years, she would play a humongous, critical role to reach Van Gogh’s work out in the world.

In this arduous task that Johanna took upon herself, she started loaning Van Gogh’s paintings to museums and that is how ‘Head of a Peasant Woman reached Stedelijk Museum in 1905 for an exhibition. It is mostly believed that the cardboard backing got added during this time and the image was framed.

Then began a trail of provenance unknown to most till it became a part of Alexander and Rosalind’s Maitland’s collection in Edinburgh in 1951. Nine years later the eminent lawyer Alexander gifted the art to the National Galleries of Scotland.

There is still so much of “unknown” left to Vincent’s and Gordina’s connect, to why Vincent took the portrait with himself to Paris in 1886, even though he never cared for what was once dawn. Why did he paint a self-portrait and not anything else on the verso of this canvas, who exactly packed it with cardboard and glue and more.

Van Gogh, least to say will remain art world’s one of the eternal fascination but by now many of us would like to believe what he wrote in one of his 700 plus letters to his brother - “Let The Rest Be Dark”.

Nilosree is an author and filmmaker