Philip Carl Salzman, a professor of anthropology at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, wrote an interesting opinion essay posted online on the Middle East Forum in which he argued that the, “Arab Middle East is missing the cultural tools for building inclusive, unified states”.

One of the leading causes for violent upheavals, Salzman concluded, and the reason why clans, tribes, sects and religions engaged in pervasive conflict is because Arab culture is little more than “displacements, expansions... conquests... invasions and dynastic replacements”.

Salzman quoted Hussain Abdul Hussain, the Washington bureau chief of the Kuwaiti newspaper Al Rai, who opined that “the Arabs are not in a wretched state — they are in a tribal state, and they are doing what they have been doing since time immemorial: conquering each other, demanding allegiance, and living in a state of perpetual war.”

Is this accurate and are Arabs condemned to practice little more than violence?

By its very definition, a tribe is a social group that existed before the development of states that, it is worth remembering, are a relatively recent phenomenon (1648).

The very idea of a state arose after the Westphalia Treaty, which ended the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648) when Spain formally recognised the independence of the Dutch Republic, and upgauged ties as it set a precedent for “states” to deal with each other in lieu of tribes.

Roots

Truth be told, all peoples and nations arose out of tribes, which brought together a number of individuals who assembled around a piece of land they developed to survive. Because of this initial quest for self-sufficiency, most resisted integration into national entities.

Where opinions differed in contemporary times, and that regrettably led to a negative definition of tribalism, was the belief that those who identified themselves as tribal people were those who followed largely self-sufficient ways of life that stood as being clearly different from mainstream and dominant members of society. Somehow, only nation-states now enjoy the monopoly of power, which allows one to conclude those who do not submit are prone to perpetual violence.

As a case in point, citizens of the United States apparently are no longer tribal because the state supplanted the Sioux, Apache and many other Indian nations that were brutally decimated. In the Soviet Union, Marxism-Leninism, assisted by the unique cruelty of Stalinism, created Homo-Sovieticus. The latter pretended to overwhelm tribal nations but these arose once again in 1990 when the USSR collapsed.

There are many other examples of utter barbarism that cover the gamut, from Pol Pot’s Cambodia to most African nation-states that left rivers of blood.Indeed, empires that rose on savagery imposed some cultural institutions, though few survived as the nation-state system came to the Arab and Muslim worlds in the 19th and 20th centuries too.

Sadly, anthropologists assumed that the phenomenon failed to anchor in the Middle East, because its inhabitants engaged in “displacements, expansions... conquests... invasions and dynastic replacements” as if these were unique to the area.

Iraq, for example, is now believed to have a population entirely immersed in tribalism that knows little more than violence. Although many Iraqis belonged to various tribal entities, it was far more accurate to note that the secularising Iraqi state, especially after the 1958 Revolution that pretended to create a new identity, strengthened national sentiments.

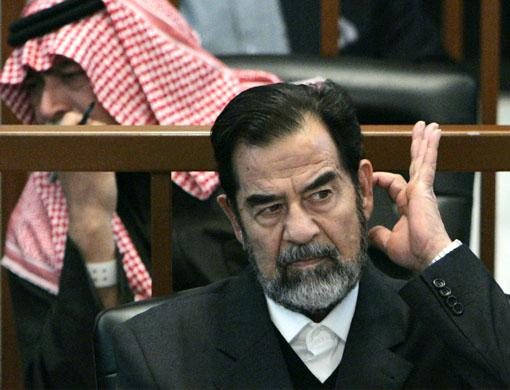

Where Baghdad failed to reach its goals was in confusing Iraqi nationalism with either the Ba’ath Party phenomenon or the cult of personality erected around strongmen like Abdul Karim Qasim or Saddam Hussain.

Consequently, Iraqis who rejected the cult of personality and found little solace in stale ideologies, laid low. They did not necessarily fall back on tribalism even if many found safe havens in one group or another.

To be sure, Iraq was a “tribal society” in the sense that most social interactions, especially familial ones, endured because of kinship and strong ties, but none of that eliminated the nascent Iraqi identity.

One may argue that Iraqis, among others in the Arab world, failed to organise their societies and engaged in acute violence because they could not shed tribal objectives, although such assertions would be gratuitous.

Which brings us back to Professor Salzman and his assertion that in this chaotic world, Arabs preferred to think of “their kin group upon which they depend for all things” versus other “groups which are by their structural nature opponents and potential enemies, and from which they can expect nothing good.”

Power, wealth, honour

“Opposition, rivalry and conflict,” said the anthropologist, “are thus seen to be in the nature of social life. Success, power, wealth and, above all, honour derives from triumphing over opposition groups. Failure to triumph means the loss of power, wealth and, above all, honour.”

In his 1975 study, The Notion of the Tribe, Morton H. Fried provided a better explanation for contemporary tribal characteristics.

He proposed that we look at pre-state bands that gained strength as modern products whenever the state expanded.

Bands comprised small, mobile and fluid social formations with weak leaders that could not generate surpluses, pay taxes and support standing armies.

In other words, the far more efficient state could provide surpluses under strong leaders, which could also defend the nation(s).

As triumphant nation-states demonstrated, success came through the imposition of violence, not any cultural institution even if time healed their voracity.

The challenge to fragile Arab states today is to apply efficient legal systems without relying on brutality, both to distinguish themselves from their more successful counterparts and, perhaps, to remove the stains associated with survival affinities.

Dr Joseph A. Kechichian is the author of the forthcoming From Alliance to Union: Challenges Facing Gulf Cooperation Council States in the Twenty-First Century (Sussex: July 2016)