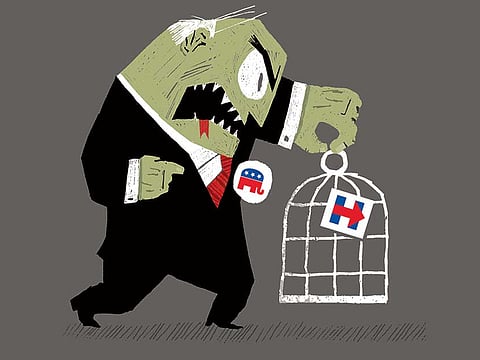

The Republican ‘lock her up!’ chants were disturbing — and inevitable

The Republican attacks on Hillary aren’t one-off reflections of the particular vulnerabilities of specific Democrats or the particular animosities of specific GOP leaders

Political conventions used to be celebratory affairs. But in Cleveland last week, the most reliable source of good cheer has been Republicans’ collective fantasy of putting Hillary Clinton behind bars.

First there were the ritualised chants of “lock her up”. Then, leading Donald Trump surrogate (and former federal prosecutor) Governor Chris Christie used his podium time to conduct a mock show trial, leading a call-and-response to delighted cries of “guilty!” The next day, a Trump delegate and adviser said that the presumptive Democratic nominee for president — a former secretary of state, senator, and first lady (whom the FBI declined to charge with any crime after a long investigation into her email practices) — “should be put in the firing line and shot for treason”. The best Trump’s spokeswoman could muster was that “we don’t agree with his comments” while reaffirming that “we’re incredibly grateful for his support”.

Trump himself seemed more restrained on Thursday night, suggesting that defeating Hillary was the preferable option when the crowd began chanting “lock her up”. But in the same speech, he referred to her record of “death, destruction and weakness” and “terrible, terrible crimes” — a tamer version of the attacks on her legitimacy that have dominated his campaign.

Analysts and pundits have tried to explain the convention’s over-the-top rhetoric and behaviour in two contradictory ways: Either Trump and his allies are engaging in a cynical strategy designed to make up for his own unpopularity by playing up Hillary’s, or he represents such a complete break from American political norms that the convention can safely be seen as a blip, an anomaly with no lasting repercussions.

Yet, in far too many ways, what we saw in Cleveland was an amplification of a disturbing 25-year trend. It is less a departure than a painful reminder of the way in which American politics — and the Republican Party — have changed. The endpoint isn’t easily predicted. But when we grasp the deeper forces at play, it becomes clear the ugliness is likely to get worse before it gets better, even if Trump is decisively defeated.

After all, GOP attacks on the legitimacy of Democratic candidates and presidents are hardly new. “Lock her up” is part of a thread that runs from conspiracy theories about Vince Foster’s death to Bill Clinton’s impeachment to Sarah Palin’s “real America” to the Birtherism that Trump espoused so fervently. Each involved fundamental challenges to not just the policies and judgement, but the very legitimacy of Democrats seeking or occupying the White House.

Nor is this just about the Clintons. Hillary is the fourth consecutive Democratic candidate to be attacked in this way. John Kerry, recipient of multiple awards for bravery in combat, was accused of betraying the United States in Vietnam by the GOP-backed Swift Boat Veterans for Truth (adding “swiftboating” to the list of synonyms for malicious slander in the American political lexicon).

And Kerry got off comparatively lightly, because his defeat cut short his demonisation. For years, Republican elites gave a wink and a nod to the baseless claims that President Obama was lying about his place of birth and was actually ineligible for office; their new standard-bearer used it as his initial foray into national politics. At the same time, more overtly, they relentlessly questioned Obama’s loyalty, faith and commitment to the Constitution. In subtle and sometimes not-so-subtle ways, Obama’s race and Hillary’s gender have added fuel to the fire of these angry portrayals, but the fire was already raging.

These attacks aren’t one-off reflections of the particular vulnerabilities of specific Democrats or the particular animosities of specific GOP leaders. They have deep roots in the transformation of the modern GOP, the structure of our political institutions and the damaging incentives that emerge from the interplay between the two.

Some of these roots are familiar. One is the spectacular growth of the “outrage industry” anchored in cable news, talk radio and the internet. There has always been a market for extremism. Now, technology makes it possible (and very profitable) to meet that demand, and indeed stoke it. Such forces exist on both ends of the spectrum, but they are far stronger and have much larger audiences on the right. (No one like Laura Ingraham will give a prime-time address in Philadelphia next week.)

Elected officials also face growing incentives to promote, or at least countenance, partisan extremism. To a steadily increasing degree, national Republicans hail from districts and states that tilt Republican, often overwhelmingly so. For them, losing the base is fatal, and they face enormous incentives to avoid being out-flanked by someone more willing to appease its anger. (Democrats confront some of the same pressures, but the lesser intensity and unity of the Democratic base means it pulls less consistently to the extremes.)

These pressures have intensified over time. As the base becomes more prominent and extreme, victory depends on getting these voters to turn out. The best way to do that is to tell your base that your opponent isn’t merely wrong or incompetent but an existential threat to your way of life and to the nation itself.

Here is where our distinctive political institutions come in. The US does not have a parliamentary system, in which one party (or coalition of parties) controls government. Instead, our system often gives control of the legislature, or at least half of it, to one party and the executive to another. As polarisation has grown, these institutions create incentives to pursue a politics of personal destruction.

The incentives have been strongest for the GOP. Not only does it have the more unified and aggrieved base; since 1994, it has built its power in Congress. Thriving in lower-turnout midterm elections and lower-population red states, congressional Republicans have developed a formidable position.

Under the tactical leadership of first Newt Gingrich and later Mitch McConnell, congressional Republicans have also determined that root-and-branch opposition to whatever Democrat occupies the White House is very effective politics. Congress as an institution isn’t popular, but it is also impersonal. It’s the person who occupies (or seeks) the White House who is the lightning rod for extremist anger. This institutional connection is a vital but neglected part of this self-reinforcing dynamic. Some Republicans have been hoping that Trump’s toxic rhetoric is just a (lamentable) part of the primary campaign that will recede once attention shifts to the general election or to governing, if he’s elected. It is not.

Fast-forward to the day after the presidential election. If Hilarry wins, is there any prospect Republican leaders will seek to find common ground? Why would they suddenly see benefit in agreement rather than obstruction? And how could they explain to Republican voters a willingness to compromise with a figure they have relentlessly attacked as a criminal? Congressional Republicans may not be able to “lock her up”, but they will do all they can to discredit her and deny her capacity to govern.

Americans shouldn’t “normalise” Trump, but they also must recognise that he is in many ways an entirely logical outgrowth of the increasing structural incentives (particularly for Republicans) to treat political opponents as fundamentally illegitimate. Unless America wakes up to this reality and starts working to change it, it can expect a continuing descent of its politics — and the party of Abraham Lincoln — into demonisation, delegitimisation and dysfunction. Or worse.

— Washington Post

Jacob S. Hacker is director of the Institution for Social and Policy Studies and Stanley B. Resor professor of Political Science at Yale University. Paul Pierson is John Gross professor of Political Science at the University of California at Berkeley. Both are authors of American Amnesia: How the War on Government Led Us to Forget What Made America Prosper.