South Sudan: Another African resource curse spectacle

The country’s leaders must not follow in the footsteps of several other nations on the continent endowed with fantastic riches yet bogged down by gut-wrenching poverty

As the world’s youngest nation and Africa’s 54th state born on July 9, 2011, South Sudan emerged from five decades of war, destruction and untold human suffering where roughly 2.5 million people mostly civilians were killed and more than 5 million others forced to live in squalid refugee camps in subhuman conditions. This was a sacrifice to be remembered.

And remembered it was at the day of Independence when thousands of people poured on to the streets of capital city, Juba, in celebration and the country’s leaders rubbed shoulders with their African counterparts who came to share South Sudan’s moment of glory.

The future looked rosy for the oil-rich country despite the enormous amount of work needed to build a nation from scratch and to heal the wounds caused by the long years of struggle.

Like all liberation movements finding themselves suddenly catapulted from being guerrilla bush fighters to state builders, problems such as leadership conflicts and resource-driven ethnic tensions were expected to emerge to test the will and statesmanship of the new leaders.

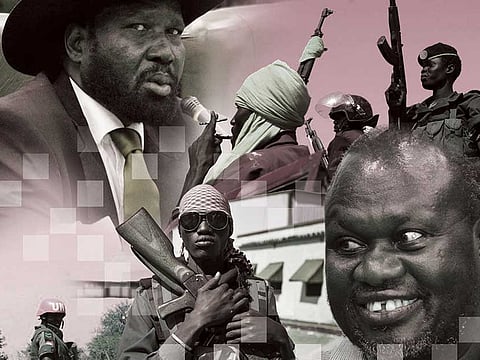

South Sudan’s hour of crisis struck in July 2013 when fighting broke out within the presidential guard on 15 December. President Salva Kiir dismissed the entire cabinet and Vice-President Riek Machar, accusing him of plotting a coup. Other prominent politicians were also arrested.

Machar managed to escape to his home state, Unity State, and soon the new conflict killed thousands of people, displaced more than 2.5 million and left some five million requiring humanitarian assistance in 2016 according to UN estimates.

It also crippled oil production, the government’s largest source of revenue. And as the peace agreement signed in 2015 and which led to Machar’s return to Juba collapsed again during the country’s fifth independence anniversary last July, Machar fled the country to neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), risking the resumption of hostilities, the further displacement of millions of people and the destabilising the whole region.

The conflict simplistically reduced to ethnic fighting between Salva Kiir’s Dinka and Machar’s Neur tribes, on a deeper level exposes a legacy of deprivation, poverty, and societal breakdown left by five decades of war which could frustrate if not totally scuttle any efforts of state building and rehabilitation.

The 50-year march to independence

When Sudan gained its independence from a joint British-Egyptian rule in 1956, South Sudan was left with the huge disadvantage of being completely dominated by predominantly Muslim North, leaving the largely Christian and Animist South left with no option but to revolt.

This Anya-nya rebellion, which started a year before independence where members of the Southern army mutinied in the town of Torit, came to an end when Sudanese leader Gaafar Nimeiry signed a power-sharing agreement with the southern rebels in Addis Ababa in 1972. But the civil war was ignited again a decade later when Nimeiry divided the south into three political regions and revoked the South’s autonomous status while adopting Sharia as the source of all legislation in the country.

This prompted Colonel Dr John Garang who was based in Jongeli State to cross to Ethiopia with many of his soldiers and create the Sudan People Liberation Army (SPLA) and its political wing the Sudan Liberation Movement (SPLM).

The civil war continued until 2005 when Khartoum government and the SPLM signed a Comprehensive Peace Agreement in Kenya in 2005 that eventually led to South Sudan’s referendum for independence.

Dr John Garang was known to be in favour of a united Sudan and even had the intention to run for president. However, his death in a mysterious helicopter crash in Eastern Equatoria State while returning from Uganda, handed the SPLM/A mantle to Salva Kiir, who was the military commander, and Machar, a mercurial personality with a history of frequently changing his positions and loyalties.

Soon after independence, it was obvious that Machar was not happy with his position as Vice-President and made his intention known to run for president in 2015. But Salva Kiir was quicker to act and Machar fled to his oil-rich Unity State, neighbouring Sudan.

Regional and international players

The war in South Sudan was long seen as a proxy war between Sudan and Uganda. Kampala supported Dr Garang’s SPLM/A to counter the perceived Islamist threat while Khartoum backed Uganda’s rebel forces such as the notorious Lords Resistance Army (LRA) and Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) and hosted Dr Machar when he defected from Dr Garang in the 1990s.

But after South Sudan’s independence, both Kampala and Khartoum saw the economic dividends of peace to be more profitable than war. Sudan badly needed the transit fees for the export of oil through its pipeline and ports while Kampala established lucrative trade with prosperous South Sudan due to its historical support for the SPLM/A. Uganda fully supported Salva Kiir when the civil war erupted in December 2013, rushing troops to guard Juba international airport and launching air attacks against Dr Machar’s positions in Jongeli state, according to rebel sources.

Significant economic interests

Sudan, which was already jolted by Salva Kiir’s decision to shutdown oil production over a disagreement on pipeline fees barely six months after independence, as well as its signing a memorandum of understanding with Kenya to build a pipeline from South Sudan oilfields to the Kenyan port of Lamu, apparently extended support to Machar. There was speculation by some sources that Machar could collude with Khartoum to deny Juba’s government of its main source of revenue.

Kenya, which has a huge banking and financial presence in South Sudan, signed a new deal with Ethiopia on the construction of a crude oil pipeline that would run from the Kenyan coastal town of Lamu to the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa.

The new deal is a part of the joint infrastructure project to integrate the region under the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (Lapsset) economic corridor.

With such significant economic interests, it is obvious that Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) member states have high stakes in a peaceful and stable South Sudan. They were instrumental in brokering the last peace agreement in August 2015 which led to Machar’s return to Juba. They also pushed for the deployment of an African Union peace force to Juba. The AU’s 4,000-strong African protection force was recently authorised by the UN Security Council. These African troops will have a broader mandate than the 12,000 UN soldiers already in the country and will be able to proactively engage those threatening civilians, according to UN sources.

South Sudan’s government seems to have reluctantly accepted the regional peace force due to a UN threat of an arms embargo if it blocks the new deployment but Juba raised objections about troops from neighbouring countries being included in the AU force.

On the international level, China — the biggest buyer of South Sudan’s oil — already committed 700 Chinese combat troops to strengthen UN peacekeeping forces and to help bring peace to the this beleaguered nation.

If history is a guide, foreign peacekeeping forces usually become part of the problem in the long run. They become stakeholders in the country’s war spoils as cartels for corruption and agents for a host of new human rights violations. It is therefore, up to South Sudanese leaders whether they would like to make their country “an island of stability” in Africa as Salva Kiir promised in one of his early speeches or become another example of a natural resource curse victim as forewarned by Secretary Hillary Clinton in reference to the country’s oil wealth: “We know that it will either help your country finance its own path out of poverty or you will fall prey to the natural resource curse which will enrich a small elite, outside interests, corporations and countries and leave your people hardly better off than when you started.”

Bashir Goth is an African commentator on political, social, and cultural issues.