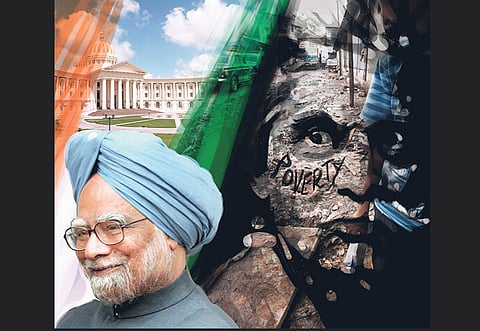

Indian identity: a study in contrast

To claim that faith has enabled people of the country to come together might seem far-fetched

In my six years as a reporter in India, it was hard not to be infected by the hubris of India — a nation that feels part of history, an essential actor on the global stage. Yet, even as I admired a country that had thrived as a democracy despite unbounded poverty, mass illiteracy and entrenched social divides, experiencing India as a reporter was a string of enervating and dispiriting episodes.

Whether I was visiting a rural police station where half-naked men were hung from the ceiling during an interrogation, or talking to the parents of a baby bulldozed to death in a slum clearance, the romance of India's idealism was undone by its awful daily reality. The venality, mediocrity and indiscipline of its ruling class would be comical, but for the fact that politicians appeared incapable of doing anything for the 836 million people who live on 25 pence a day.

The selling of public office for private gain was so bad that the only way to make poverty history in India would be to make every person a politician.

The burden of democracy in India, to borrow from Yeats, the Irish poet influenced by mystical Hindu thought, was that "the best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity". Yet the country continues to confound those who write it off.

I saw India redeemed repeatedly by three quirks of history: a written liberal constitution, religions rendered ethical and a talent for sabotage. Take the last first. India won independence not through war or revolution, but through non-co-operation, protest and the quiet subversion of the economy. Civil society in India has acquired an unrivalled mastery of such skills and campaigners have been quicker than politicians to realise that democracy will not prevail unless its proponents show success at governing. Consequently, it was activists who shamed the government last year into enacting a law to make children's education compulsory.

India's constitution, the longest in the world, has become a moral compass for justice in a society where violence had been the best measure of one's power and standing. When homosexual sex was legalised by Delhi's high court last summer, the judges said the old law criminalising the gay community was in violation of the constitution.

To claim faith has enabled Indians to come together might seem far-fetched. One of my first reporting tasks was to visit Muslim victims of state-sponsored pogroms. Yet, such violence appeared more political than theological. Indeed, during my time in India, it was Europe that appeared unable to embrace religious diversity. While I awoke each day to the sound of the muezzin, the Swiss voted to outlaw the construction of minarets.

India's philosophy emphasised not what you believed but how you behaved. Lead a compassionate, religious life and the state would leave you alone. This thinking meant Indian streets are shared by people who look, dress and pray differently — making them a celebration of the nation's diversity.

Diverse, yes: but it's an open question whether the society being created by these forces is a fair one. India is perhaps the most unequal country on the planet, with a tiny elite engorged on the best education, biggest landholdings and largest incomes. Those born on the bottom rungs of the social hierarchy suffer a legacy of caste bigotry, rural servitude and class discrimination.

Politics in India is increasingly becoming a debate about the haves and have-nots and this is given violent expression by a rise in bloody Maoist guerrilla terror.

Britain may see itself as a major power, sending troops to pacify Islamist fighters and spreading good governance globally. These delusions will leave the UK morbidly disappointed. Unlike Indians, the British are not on the cusp of a stirring transformation. Overspent and overstretched, they perch instead on the crest of a falling wave.