Further darkening of the horizon

Continued violence in Afghanistan seems to queer the pitch for US-Pakistan relations even as the Bonn conference fails to offer any potent solution

This was to be the season of hope in and around Afghanistan, but what we have instead is a further darkening of the horizon. Relations between Pakistan and the United States remain severely strained. The long awaited Bonn Conference has not even remotely lived up to its promise. No less ominously, violence in Afghanistan suddenly wore a new garb on the Ashura, the 10th day of Muharram.

It is probably an index of personal shock that I turn to the third factor first. Having lived in Kabul for four years and followed events in Afghanistan professionally for the last three decades, I am all too aware of ethnic and other divisions in the diversely constituted Afghan society, but sectarian violence was never a significant fault line.

In the social hierarchy, perpetuated by the Durrani state created by Ahmad Shah Abd Ali in the mid-18th century, social groups such as the Hazaras, who practice Shiite Islam, got relegated to a lower order only on ethnic and linguistic grounds. The American military intervention in 2001 reversed this trend as it dispossessed the predominantly Pashtun tribes of power and upgraded other ethnic groups. The backlash and resistance from Pashtun Taliban, however, articulated itself in political terrorism and not sectarian violence.

It has been a battle of turf and not of sects during the last decade. Unlike Iraq, where mysterious forces transformed the post-Baathist conflict into deadly sectarian combat, the Taliban fought the US, Nato and the Karzai government in the name of Islam and national sovereignty. They were quick to dissociate themselves from the most extraordinary attacks on Shiite gatherings in Kabul, Mazar-e-Sharif and Kandahar that left 59 dead this Ashura.

Pakistan has faced a similar phenomenon in recent years though the government mounted a huge security operation this year and ensured total peace for the large, emotionally charged, Muharram processions.

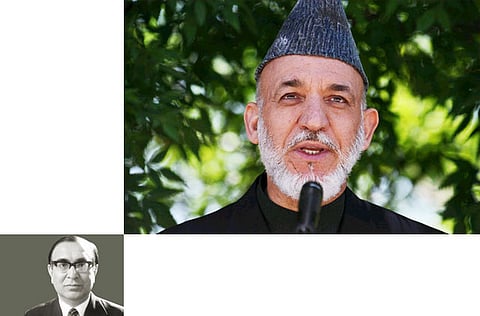

Unsubstantiated claim

Unable to provide any other explanation, President Hamid Karzai made an unsubstantiated claim that the unprecedented sectarian violence in Afghanistan was the work of a banned extremist Sunni organisation rooted in the Punjab province of Pakistan. He offered no explanation how this outfit could operate as far away from Pakistan as Mazar-e-Sharif.

Pakistani analysts stopped taking Karzai's allegations seriously some time ago, but remain deeply preoccupied with the possibility that an invisible hand is stoking a sectarian fire now in Afghanistan. There was the carnage in Iraq. Pakistan itself was rocked by sectarian tensions despite a long history of Shiite-Sunni harmony. Iran produced evidence that a small militant Sunni group, Jundullah, was using Pakistani soil to launch murderous attacks in Iran at the behest of CIA.

Western think tanks regularly underline the supposed fragility of the oil-bearing eastern provinces of Saudi Arabia because of their Shiite population.

Last but not the least, the current Syrian harshness is being increasingly portrayed as rooted in a sectarian Alawite vs Sunni contest for power. It seems the region will hear a lot more of the so-called Shiite-Sunni "contradiction" in the months ahead.

Despite a decade that separated it from the earlier path-breaking Bonn 1, the Bonn Conference of December 5 (Bonn2) ended with an impressive communique, but little measurable progress towards reconciliation and reconstruction.

Not enough progress

Not enough, if any, progress had been made in contacts with the Taliban to seat them amongst the 90 states and 15 international organisations.

Reeling under a lethal Nato Special Forces attack that obliterated a Pakistani check post near the Afghan border, an attack noted for its duration and precise targeting of all the 49 Pakistani soldiers — Pakistan had stayed away from Bonn 2. In its simplest formulation, the conference looked stalemated between the American doctrine of "fight, talk and build" and the rest of the world, including the otherwise absent Pakistan and most of the European powers, veering round to a new approach described as "talk, talk and talk" after a futile 10-year old military campaign. Pakistan is still maintaining a stoppage of Nato supplies imposed after the destruction of its Salala check post.

Efforts are afoot to de-escalate tensions between Islamabad and Washington, but are regularly endangered by Washington peppering up peaceful overtures with gratuitous threats.

Meanwhile, issues between the two so-called allies have unleashed undercurrents that endanger the stability of Pakistan's elected government. An act as natural as President Asif Ali Zardari seeking medical treatment in the tranquillity of Dubai has let loose a storm of rumours, each darker than the other.

But of that, another day, another column.

Tanvir Ahmad Khan is a former foreign secretary and ambassador of Pakistan. He is currently the chairman and director general of the Institute of Strategic Studies in Islamabad.