Don’t despair, a silent majority can still keep Britain in Europe

Brexit dominates the debate, but shouldn’t we also consider the benefits of a popular vote to stay. The whole atmosphere of the UK, and Europe, could change

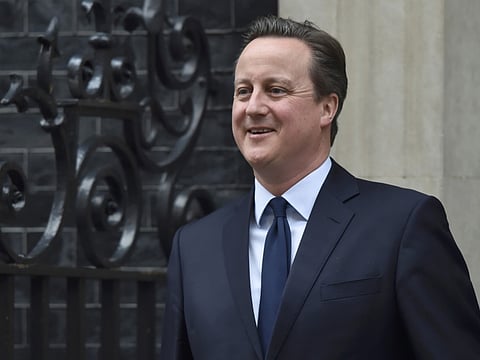

What if we wake up on June 24 and discover that the great British public, in its abiding wisdom, has voted to leave the EU? The pound plummets. The London stock market is in collapse. British Prime Minister David Cameron resigns. Nicola Sturgeon initiates another Scottish referendum — and jubilant crowds, waving union jacks, pack Trafalgar Square to hail the smashing of the Brussels “shackles”.

But what if the script runs rather differently?

What if, despite opinion polls that have tightened, and even tipped over to “leave” in recent months, we wake up on that Friday to learn that there has been a convincing vote to “remain” — with a majority larger than the 55-45 margin by which the Scots voted to stay, if not quite as big as the 67-33 result of the 1975 referendum? What if the crowds thronging Trafalgar Square are waving the EU flag, too, and the two flags are flying side by side from government buildings the length of Whitehall?

What if a beaming Cameron accepts congratulations in French, and a radiant German Chancellor Angela Merkel flies in for dinner?

Now I know that, as of today, such a turn of events might look unlikely. And my own feeling about the likely outcome has swung wildly in recent months. When the referendum became inevitable after the Conservative victory last May, I was confident that a yes was likely, even with a slim majority. If Scots — with all the nationalist passion behind their independence campaign — had nonetheless rejected a plunge into the unknown, how much more likely were the famously cautious UK voters to favour the status quo?

By summer my confidence had ebbed. Representatives of big and small business can dispute whether the EU is better or worse for their own, and the nation’s, prosperity, and executives can sign as many rival petitions as they like. But the national mood is never far from the economic argument, and referendums can easily turn on issues extraneous to the question asked. The flow of refugees and/or a terrorist attack could quickly shift the vote from a fairly passive remain to an angry leave.

Security is a prime duty of government. The sight of EU borders — external and internal — so manifestly out of control as they have been over the past year saps faith in government generally. Nor have UK ministers — or “remain” campaigners — done nearly as much as they could have done to hammer home the fact that, as a non-Schengen country, the UK retains responsibility for its own borders, and any failures of security are its own.

FDFDFDFDFDFDF

The virtual slanging match between past UK intelligence chiefs and former CIA bosses in the wake of the Brussels bombings, as to whether the UK was safer inside or outside the EU, has been entertaining, but largely irrelevant. The central point is that the UK — unlike non-EU Norway, for instance — is not, and will not be, in Schengen. You could make a case for saying it should be (and in the euro, for that matter), but the fact of the UK’s non-membership of Schengen is simply not getting through.

Yet how much, in the end, will even such an emotive matter as refugees affect the vote? We remainers have long argued that the strength of the leavers’ appeal resides less in any facts or figures than in the depth of their sentiment: their feeling that the UK is historically, culturally, viscerally, different from continental Europe (plus, of course, resentment that there had never been a straight in-out referendum before).

But are we perhaps underestimating the depth of sentiment on our own side? Two generations have grown up inside what is now the EU: a common sphere for travel, jobs and culture that is taken for granted. The modern world has thrown us together. You have only to go to, say, Australia, to appreciate how European the UK has become. And the EU’s appeal — as the Ukraine crisis, and now the refugee situation, shows — extends well beyond its borders. Could it be that, as in Scotland, there is a quiet majority of voters, undercounted by the pollsters, who will flock to the ballot box and endorse the status quo?

And if there is a majority to remain — a majority that is solid, rather than timid — the whole atmosphere of the UK, and Europe, could change. The UK’s Europe “complex” might not be entirely laid to rest — many Scots, after all, kept their appetite for independence after September 2014 — but sceptics could no longer complain that they had not been asked, and future UK prime ministers would know that they no longer had to be mealy-mouthed about Europe. They could boast back home about the UK playing a full part.

Within the EU there would not only be profound relief on the part of those concerned that a vote for Brexit would trigger centrifugal chaos, but a new openness to listening and cooperation on both sides. There would be a chance for a new collegiate approach to everything, including refugees and security, and the UK would be taken all the more seriously because its commitment was no longer in doubt. There are, it is rumoured, moves afoot among our continental cousins for a “hug a Brit” campaign before June 23. Let’s dare to hope that, when all the votes have been counted the next day, it turns out that we standoffish islanders have hugged them back.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Mary Dejevsky is a writer and broadcaster and a member of the Valdai Group and a member of the Chatham House think-tank.