Staring at the blackboard and listening to the teacher’s voice drone on, I could feel my eyelids begin to droop. “Keep awake,” I chastised myself as the children listened to how Earth rotates on its axis. I was crammed into a dusty classroom with 60 children aged around 10. “Repeat after me,” the teacher commanded, pointing towards the board.

I was only a week into my two-month volunteer teaching placement at a remote school in Ghana, West Africa, but was already stunned by the lack of creativity and stimulation in the classroom. The children looked as bored as me, but they were the lucky ones – at least they got to go to school. Many children didn’t get that chance.

I was worried. At a time when learning should be fun, entertaining and enriching, it was mundane and seemed pointless. The children were learning about things that had no relevance to their lives. But what could I do?

It made me realise how fortunate I’d been. I grew up in a middle-class London family with my parents Barbara and Richard, elder brother James, 36, and younger brother Guy, 29. I did quite well in my studies and became a lawyer.

I’d been expecting to be busy on a case for the entire summer, so when it was suddenly cancelled, I found myself with annual leave but no idea how to spend it.

A chance meeting with a friend, Joel, at my cousin Eve’s 30th birthday party solved the issue. Eve had been to Kolkata, India, the previous summer with a charity Joel worked for. “Interested in volunteering as a teacher in Africa?” he asked me.

I didn’t hesitate to say yes. I’d always loved travelling, having spent two months going from Kenya to South Africa while at university. I also had a passion for teaching, so, excited, I signed up and paid for my airfare and accommodation.

Back to basics

Three weeks later I was on a plane to Accra, the capital of Ghana. My home now was Jisonayili in Tamale, a town in the north of the country. Many of the villagers lived in mud huts, with no electricity or water.

In my first week I taught an average of 54 students in one class, with four students poring over one textbook. “Put up your hand if you have books at home?” I asked the children one day. Not a single hand went up. It upset me so much that I asked the volunteer coordinator, who was arriving in Ghana from London, to bring along books, games and puzzles.

With the resources I set up a community-run play centre within a school. I also trained a local librarian, Awol, to teach children the games in a lively way.

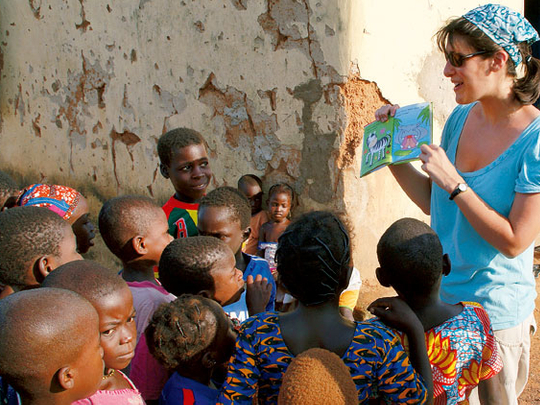

Teaching in Ghana and Uganda is almost always by rote. Kids have no games or experience of discovery-led teaching. I decided to focus on learning through play. Kids were encouraged to participate and given lots of praise and encouragement.

This was a hit and the children became excited by even the most simple toys. It was brilliant to see the children animated and having fun while learning about shapes, colours and numbers.

All too soon my stay was over, but I left Ghana with the image of their happy faces ingrained in my mind.

I desperately wanted other children in rural villages to receive access to quality education, but it had to be done in a sustainable way. It was all I could think about back home.

A life-changing decision

Just three weeks after landing back in the UK, I made a decision. “I’m quitting my job,” I announced to my boss, family and friends.

“Don’t be silly,” they all said. But I was serious about going back to Ghana to set up more play centres and train people to use their local resources.

So a few of my friends supported me – some even ran marathons to raise money for my project. They also paid to see me sing at a concert I put on to raise funds.

In the months before my second Africa trip, I spent all my free time researching early childhood development – I wanted to know the best way to teach these children. I found that learning through play in early childhood was crucial to help them grasp concepts.

In January 2008, a year after I first visited as a volunteer teacher, having raised £1,000 (just under Dh6,000), I returned to Ghana.

There I met David Abukari, a community development worker who loved my play centre idea. He took me to a remote village on his motorbike and introduced me to village elders who helped me organise community meetings to tell parents – some of whose children had never gone to school – about my plans.

I lived in a mud hut with a few volunteers in a village in northern Ghana. I commissioned local carpenters to make wooden games and asked expats in Tamale to collect cardboard boxes, bottle tops and buttons for them.

It took David and I nearly three months to train teenage volunteers from villages who’d never had a job to run the centres, but this was extremely important to me, as I wanted the locals to be running their own communities.

At the end of the training we held a graduation ceremony and enrolled 120 children at the centre, where toys, puzzles and charts were used as tools to help children learn. The volunteers started using their training to teach the children each afternoon.

The kids at the first centre were so thrilled to finally learn how to count and identify colours that David and I set up two more in neighbouring villages. All three centres were set up using the £1,000 I raised.

Jumping educational hurdles

After five months in Ghana I went to Uganda for a friend’s wedding, leaving David to supervise the centres. I discovered on my first day there that it was facing the same educational hurdles as Ghana, after meeting Sarah Kanyonga, a former teacher.

Like a surrogate mother to the others in her village of Bukaya, South Uganda, she’d formed a self-help group for HIV/Aids widows.

Sarah asked me to set up some play centres there, and train these women to run them. They were some of the world’s poorest, all illiterate and painfully shy. One woman, Robina, was raising her orphaned grandchildren alone with no job, no income and all while she was going blind due to a degenerative eye condition.

By the end of the three-month training, the women were much more confident and better able to teach the 160 children from the surrounding villages.

By late November 2008 we’d created seven play centres in Uganda, in the schools, churches and community buildings there, working with local organisations using money we’d raised plus some more that came in from donations from people in the UK.

I could see there was potential for more centres, so I set up a charity with both David and Sarah as managers. Because I wanted to instil in the children a thirst for learning, I called it Lively Minds.

My savings had now run out but I’d been offered a legal job in London, so I accepted and flew home in order to get some more money to keep the schools open.

From the UK, I dedicated one day a week to Lively Minds on a voluntary basis, plus my entire weekends and annual leave while holding down my full-time role. It was exhausting but rewarding.

By the end of 2011, Lively Minds had established 18 play centres each in Ghana and Uganda. I also launched a child-sacrifice-prevention programme in Uganda with Unicef.

I heard about child sacrifice by accident. One day Sarah and I were walking through a Ugandan village and a huge group of children were following us. They were fascinated by us and were trailing us just for fun. “I’m worried that parents will think that we’re abducting the children to sacrifice them,” Sarah said. Seeing my horrified face, she sat me down to explain.

Hundreds of Ugandan children were apparently being kidnapped by witch doctors. They also promised desperate parents power, prosperity and wealth if they would allow their children to be sacrificed. Most children would later be found dead in bushes. I wondered what could be done to help save the lives of these innocent children.

On my first trip to Uganda I met local author Oscar Ranzo. Now back in the UK, I learnt he’d written a story called Saving Little Viola, about a girl who is saved from being sacrificed. Although it was a children’s book, I realised it could be used as a powerful tool to make people aware of this deadly ritual.

I devised a lesson plan for teachers at the centres in Uganda, which involved reading the tale aloud and asking children questions. Oscar loved the idea and agreed to run the programme.

To date we’ve run 55 school workshops for more than 7,000 children in Uganda. One month after we began them, the percentage of students believing that child sacrifice made people rich dropped by half.

The children have also learnt how to protect themselves. They avoid being outside alone late in the evening and they are prompt in voicing their fears and suspicions about people to their teachers and parents.

Thanks to our anti-sacrifice campaign, we’ve managed to break the cycle of belief and ensure that future generations do not turn to it.

Over the years, Lively Minds volunteers have given more than 13,000 children the opportunity to learn by playing using practical, stimulating and interactive educational games.

In May this year, I was ecstatic to be awarded a grant by the UK-based Waterloo Foundation allowing me to work full-time for Lively Minds.

Our plan is to set up play centres in 50 villages, training more than 1,500 women and teaching an extra 6,000 children.

Most of the money for our projects comes from grants from charitable foundations, companies and generous individuals, but we also hold our own fundraisers.

Five years ago I never imagined I’d be running a charity and spending half my life in Africa, but it’s certainly the most worthwhile way I can think to spend my days. I feel very lucky to have been able to make a difference to so many people.

● Alison Naftalin, 33, splits her time between the UK, Ghana and Uganda

Tell us the story…

Do you know of an individual, a group of people, a company or an organisation that is striving to make this world a better place?

Email us at friday@ gulfnews.com or the features editor at araj@gulfnews.com